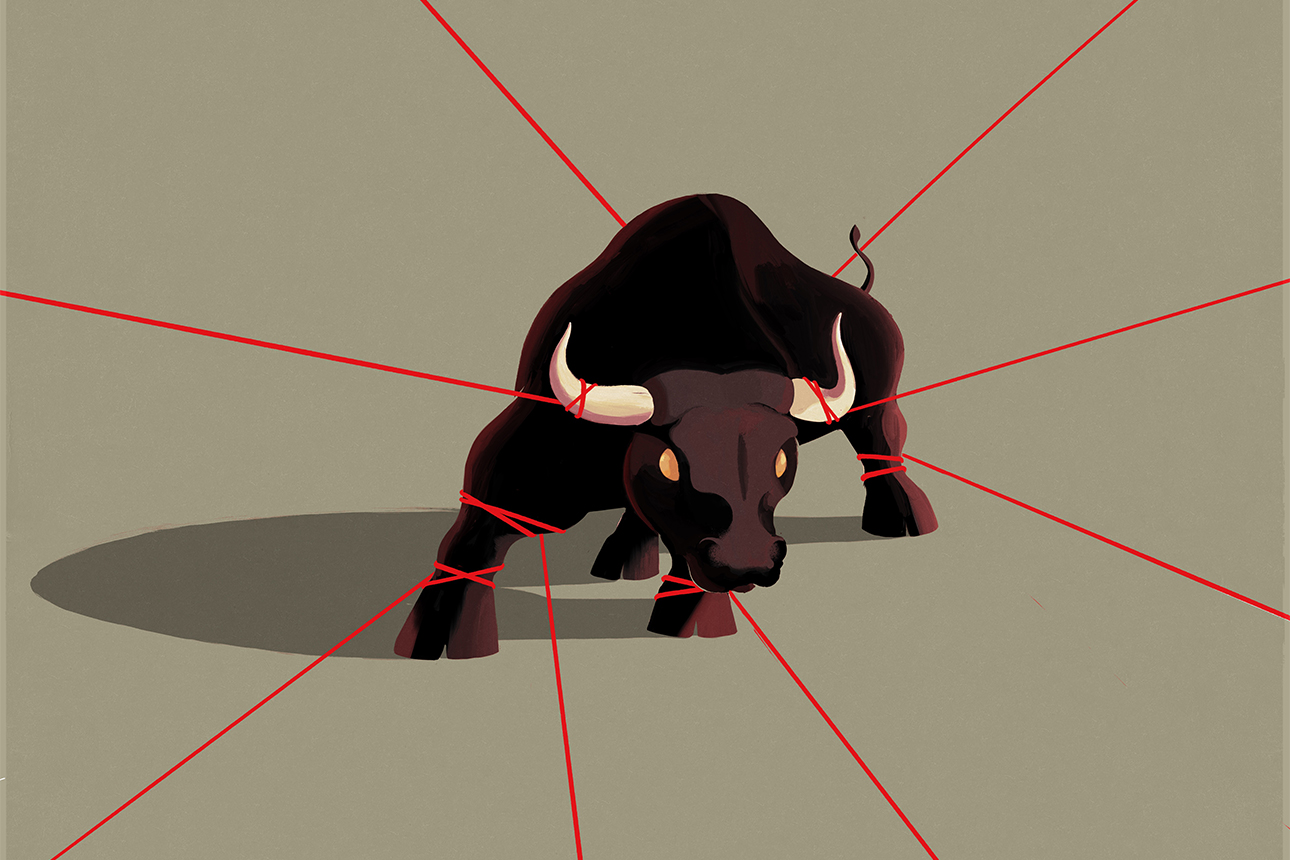

The Case Against Restricting Stock Buybacks

A large-sample study of share repurchasing finds that most criticisms against the practice appear to be unfounded.

Topics

Frontiers

Carlo Giambarresi/theispot.com

Are stock buybacks as bad as they’re made out to be? The ubiquitous corporate practice of repurchasing shares has been the focus of much political and media scrutiny. The federal Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 included a 1% excise tax on repurchases (which President Biden has proposed increasing to 4% in his 2024 budget). In addition, senior Democrats have shown interest in barring executives from selling shares for three years after a repurchase, the federal government has suggested that companies that give up buybacks will receive preferential treatment, and the Securities and Exchange Commission has proposed a significant increase in the extent and frequency of repurchase reporting.

The debate on the economic consequences of stock buybacks has so far tended to focus on small samples or cherry-picked examples. Given that thousands of companies repurchase their shares each year, and aggregate repurchases have exceeded $500 billion annually for the past five years, we decided that a large-sample study of repurchasing behavior was warranted. Our study, published in the journal Financial Management, outlines the benefits of the practice, as stated by its proponents, and provides evidence that casts doubt on the alleged costs cited by its critics.

Get Updates on Innovative Strategy

The latest insights on strategy and execution in the workplace, delivered to your inbox once a month.

Please enter a valid email address

Thank you for signing up

Critics of buybacks typically make three arguments against the practice. First, they claim that share repurchases enable companies to manipulate the market either by increasing the demand for — and therefore the price of — shares or by tricking naive investors by inflating earnings per share (EPS). Second, they allege that share repurchases enable insiders to benefit through compensation contracts or the sale of shares at inflated prices. And lastly, critics charge that share repurchases crowd out investment and thus sacrifice innovation and long-term economic growth.

Meanwhile, those who support or engage in stock buybacks offer several justifications for the practice. First, payouts to shareholders align manager and shareholder incentives by reducing the potential misuse of free cash flow. Second, using repurchases instead of or in addition to dividends gives corporations flexibility in the amount of cash returned to shareholders, the ability to award repurchased shares to employees as equity compensation, a modest tax advantage to shareholders (less pronounced since the 2003 dividend tax cut), and the ability to signal the company’s good prospects to the market. Finally, share repurchases represent well-disclosed and regulated arm’s length transactions at current market prices between willing participants.