The Entrepreneur’s Path to Global Expansion

As entrepreneurs are considering international expansion earlier and earlier, it is crucial that they structure their ventures to anticipate and mitigate the tensions that can arise from the ongoing need to match perceived opportunities to available resources.

Topics

For much of the history of modern business, entrepreneurial ventures were inherently local during their early years. Most startup companies today, however, consider overseas expansion from their inception.1 Several developments have facilitated the trend. Technological progress — including the development of fast, low-cost telecommunications connections and the advent of the Internet — plus international airline competition and lower cross-border shipping costs for goods make it seem temptingly easy for startup companies to venture abroad.2 Yet it requires a lot of management bandwidth and experience to do things right.3 Entrepreneurs and their managers often underestimate the cost of an expansion move to foreign shores and, more critically, lack a clear conceptual framework for international expansion. Too often the results are haphazard decision making, insufficient intracompany communication and even financial disaster.

Many entrepreneurs behave reactively, expanding abroad in response to stimuli rather than according to a thoughtfully crafted strategy. Granted, it is hard for a company to develop a clear international expansion plan when its business model and organization are new, untested and still evolving. But there are some topics and dimensions with which entrepreneurs should be familiar. Over recent years, I have studied entrepreneurial ventures in more than 20 countries, many of which had expanded across borders. Examining why some of these ventures failed while others succeeded, patterns emerged. (See “About the Research.”) Ventures followed different expansion paths and the best entrepreneurs successfully anticipated and managed the tension that arose along these paths. To understand this, it is useful to view the path taken by an entrepreneurial venture as an ongoing matching of its perceived opportunities to its available resources.

Opportunities come in many different forms: demand for a new product or service, or for an existing product or service delivered at lower cost or through a new business model. Selling existing products or services in new geographic markets also represents an opportunity. Common to opportunities is the uncertainty about their size and exact nature. Customers almost never accept an entrepreneurial idea in its original conception. In most instances the entrepreneur needs to experiment before finally getting it right.

Resources comprise everything that the entrepreneur might enlist to pursue an opportunity. Most novice entrepreneurs think primarily of financial capital when they think of resources. But there are many other resources that are less obvious. These include specific talent and human capital, specific information useful for pursuing a business opportunity and risk-capital providers that can offer more than financial capital — namely, expertise and deal-structuring advice. Also crucial for entrepreneurs are social and professional networks. Often these networks form the basis for a venture’s success because they provide unique and timely access to the more visible resources such as capital and management talent for a startup company.4

Most entrepreneurs first see an opportunity andthen think about the best way to accumulate the resources needed to pursue it.5 However, the key skill entrepreneurs must master is the art ofcontinually matching opportunities to resources6 That ongoing experimentation is what determines the structure of an entrepreneurial venture on both strategic and organizational levels. The mapping of opportunities to resources is particularly useful with respect to the question of international expansion. Going abroad can significantly increase opportunity inasmuch as it expands the market for existing product and introduces the possibility of product-line extension. Similarly, setting up a subsidiary abroad can afford a company better access to resources such as capital, well-trained managers and engineers, and specialized supplier services. Often entrepreneurs expand both to enlarge their opportunities and to gain access to more resources, but sometimes they expand for just one of these reasons.7 The more successful ventures in the research were able to define precisely and communicate within the company the reason or reasons for which a strategic investment abroad is being made.

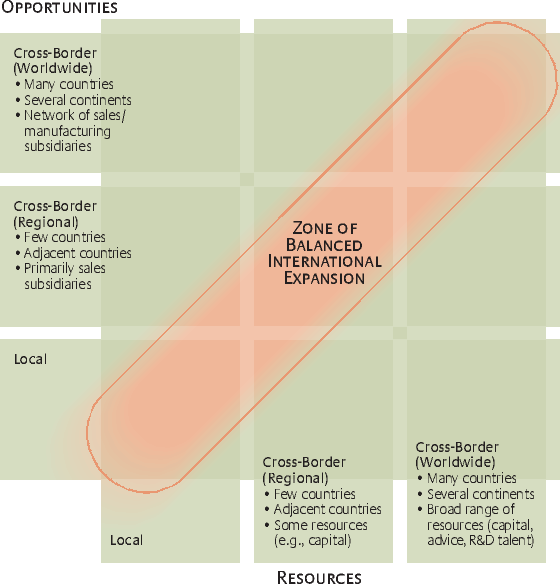

The International Expansion Matrix

How do businesses typically expand across borders? What patterns are observed among high-performing ventures and what lessons can be drawn from them? To answer these questions, it is useful to think of the international opportunity facing a venture as a continuum that ranges from purely local to worldwide.8 We can think of resources the same way. If we then juxtapose these two continua, we create aninternational expansion matrix.9 (See “The International Expansion Matrix.”) This matrix defines the choices that a venture has at its inception and throughout its life. The matrix can be used not only to assess and direct a venture but also as a tool for communicating with investors and employees. Even though startup companies are small and one would expect communication within such companies to be straightforward, given the high level of uncertainty inherent in new ventures, there is a particular need for clear messages to employees, investors and customers.

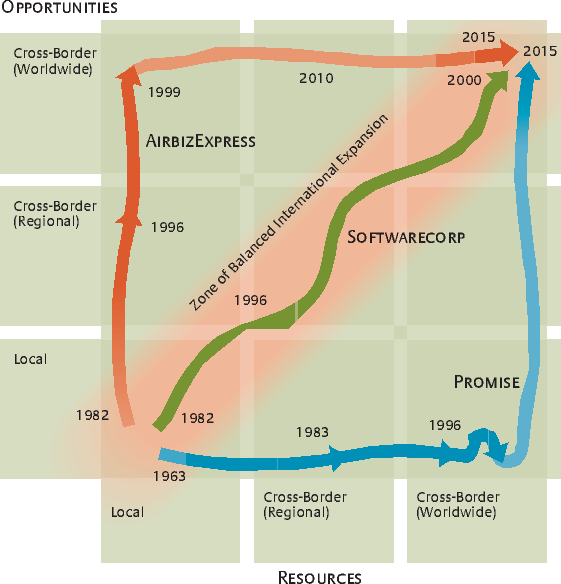

To understand the connection between the international expansion matrix and the development of a venture, first consider the path taken by Softwarecorp (not its real name), a typical company organized around a software design that the founder had explored in his engineering doctoral thesis. (See “Three Paths of Entrepreneurial Expansion.”) The engineer initially bootstrapped development. As his idea evolved into a clear commercial vision, however, he sought first-round venture capital, which a local financier provided. (First-round venture capitalists do not like to invest in companies they cannot easily visit during a day trip.) For the second financing round, the entrepreneur was able to attract funding from a foreign venture capitalist. He also started selling his software in neighboring countries and later on a worldwide scale. On this path, expansion occurs in a balanced way, starting in the lower left-hand corner of the diagram and moving up and to the right as geographic expansion of opportunities is pursued and resources are mobilized simultaneously. An entrepreneur spots a local opportunity and accumulates local resources with which to pursue it.

As an entrepreneurial company grows, opportunities and resources both change. If, for instance, the company hits opportunity limits in its local context, an obvious way to keep growing is to diversify into other products and services. Another way is to expand geographically. Almost all the companies studied had given serious thought to geographic expansion. Like the Softwarecorp founder, many started with a low-cost test in neighboring countries rather than an expansion into far-flung locales. Thus a U.S. company would start by selling its products in Canada; a French company, by expanding into Belgium or Spain.

As companies grow, resource options also change. Initial local success will often enable a company to attract geographically distant resource providers including large private equity investors, banks, public equity markets abroad and large customers offering lucrative nationwide or even supranational contracts.

If things continue to progress well, a company will, like Softwarecorp, pursue its business opportunities beyond a regional scale and expand worldwide, drawing on an international base of resource providers. Erstwhile entrepreneurial companies such as Microsoft Corp. and Dell Inc. are operating at that level; companies such as Starbucks Corp. and Google Inc. are well on their way.

The balanced expansion path is a useful standard against which to judge a venture, and many companies follow it. But off-diagonal strategies are common and, for some ventures, work much better than the balanced path. (See “Three Paths of Entrepreneurial Expansion.”) For example, a venture such as air-freight delivery service AirbizExpress (not its real name) progressed from pursuing local opportunities with local resources to pursuing cross-border opportunities with local resources and then eventually to pursuing cross-border opportunities with cross-border resources. However, Promise Co. Ltd, a highly successful entrepreneurial company that is among the top four providers of unsecured consumer loans in Japan, began by pursuing a local opportunity with local resources, and then added cross-border resources before finally pursuing cross-border opportunities. Pursuing an off-diagonal path may be the optimal choice for a company, but it creates tensions that the entrepreneur needs to anticipate and manage.

Which Starting Position Makes Sense?

The research examined the initial opportunity/resource positions of 27 ventures. (See “Starting Positions for International Expansion.”) As might be expected, the majority of companies start out pursuing a local opportunity with local resources. Fewer start life pursuing a global opportunity or drawing on a global resource base. Still fewer begin by pursuing a worldwide opportunity with worldwide resources; it is extremely difficult and complex to coordinate such a constellation, particularly considering the tenuous nature of a startup’s nascent organizational culture. The research shows that, more often than not, entrepreneurial ventures that start in the upper right-hand corner of the diagram end in financial and personal disaster. One company expanded to three different countries before generating any significant revenue at home. The entrepreneurs and their financiers had a rosy view of how business would take off simultaneously in all four countries. The company folded after less than two years

Another example is Boo.com, founded in London in 1998. With the goal of becoming the first global fashion e-retailer, it set up offices in the United Kingdom, the United States, France, Sweden, the Netherlands and Germany, offering service in seven different languages and in 18 different countries. It also raised $135 million from investors in the United States, Europe and the Middle East.10 Overwhelmed by the challenges of global logistics and cross-border technology management, it failed after 18 months. The company would have been well advised to start with a local opportunity and local resources, then refine the model and expand from there.

International expansion does not make sense for all businesses. It might seem obvious, but many entrepreneurs can be swept up by the buzz around globalization. Opportunity-oriented expansion into other markets, in particular, sometimes seems easier than it is and can seduce entrepreneurs who would be better off remaining local. For example, Cityspace Ltd. developed a networked electronic-kiosk system to inform London tourists of their whereabouts and provide tips on restaurants and theater venues. The company made money primarily through advertising and commissions on bookings. The preliminary business plan called for expansion to other cities that attracted large numbers of tourists: Paris and Rome, for example. Initially, the hard part appeared to be technology development, and the entrepreneurs believed that once they were done, expansion abroad would be relatively easy. They soon came to realize, however, that much of their business success depended on the location of kiosks, on a detailed understanding of the local tourist market, and on their own connections to local restaurants and theater operators. “Our business has a lot of similarities to retail,” states one founder. “Our service has to be in good locations or potential customers will never know it exists.”11 To move to a major city in another country would thus be nearly equivalent to starting from scratch. The company consequently chose to focus only on London and a few other select U.K. cities.

At the other end of the spectrum that extends from purely local are startup companies whose very business models are based on some form of cross-border transfer of information, services, goods or resources. These companies need to have a cross-border orientation from the start and are often born as cross-border entities or expand within the first months of their existence. “Born global” companies typically start out either on the left-hand side of the international expansion matrix (if they pursue a cross-border opportunity), or they start out along the bottom of the matrix (if they use cross-border resources).

An example is Boston-based Internet Securities Inc., which began as a supplier of business information on emerging markets. Most of its initial customers were in the United States and Western Europe, but most of the sources of original information were in Eastern Europe. The company had to set up shop not just in its major markets but also in all the countries it covered. The business model required more than $10 million upfront, which was provided by venture capitalists in Boston. Thus, the company’s starting position was one with local resources and a worldwide opportunity, in the upper left-hand corner of the international expansion matrix. Yet even in this type of company, further international expansion involves growing pains. “We were close to the revenue targets of our original [business] plan,” says one founder. “The problem was that our costs were much higher than expected. We did not realize how much it costs to run a global company, so we underestimated the costs above and beyond those of individual country subsidiaries.”12

Companies that start out along the bottom of the international expansion matrix pursue highly local opportunities but are able to attract resources from far-flung sources. (Generally speaking, this starting combination is less common than the starting combination of a cross-border opportunity and local resources.) For instance, in the case of QI-Tech, one Western entrepreneur entered a 50–50 joint venture with a Chinese state-owned company that was exporting parts to Europe for the manufacture of three-dimensional precision measurement machinery. The Chinese partner contributed capital and a work force. With his considerable expertise in the technology behind the manufacturing of the machinery, the entrepreneur arranged for Chinese engineers to receive training in its design in the Netherlands, and he recruited a number of senior foreign managers to work in China on a temporary basis. “The support from [foreign] technical experts … was invaluable,” reports a senior manager of this entrepreneurial joint venture. “We would not be where we are today without their technology.”13 The joint venture company was thus able to produce the machinery locally — a China-centric opportunity with access to resources worldwide.

Managing Tension on the Expansion Paths

Many ventures deviate considerably from a balanced expansion path. Even those that take a relatively balanced path rarely follow a straight line because their access to expanded opportunities and resources is often disproportionate and driven by factors outside their control. Macroeconomic events in other countries, for instance, might increase the availability of equity but have little impact on consumer behavior. Structural barriers, such as legal requirements for creating a subsidiary or labor laws that limit the pursuit of foreign opportunities might come into play. Other barriers such as the structure and bylaws of venture capital funds, auditing requirements and foreign exchange controls might disproportionately affect cross-border access to resources.

Such deviations from the diagonal create tensions, often extreme ones, within a venture. Entrepreneurs who best anticipate these tensions are best able to manage them.

Many business models are so tailored to local demand that the cost of adapting them to another market far exceeds the benefits of doing so. Some business models are almost impossible to transfer across borders. In the case of Promise, the Japanese consumer-loan provider, loans (of up to $5,000) are paid out in cash at vending kiosks — typically within 30 minutes after receipt of information about the applicant’s employment and social security status. Many elements of the decision-making process are idiosyncratic to Japan, and the potential for fraud is enormous by Western standards. Even though the need for fast cash exists the world over, it would be difficult for the company and its competitors to replicate this model elsewhere. Too many elements would need to be changed simultaneously.

Good strategy is a function of knowing what things are important for a business to get right and what opportunities can be ignored or deferred. It can make sense, however, to run experiments to see whether a business model can be expanded geographically. It is generally a good idea to keep such experiments small and contained. Promise experimented with a foray into Hong Kong, and because it kept the scope of the initiative modest, the company did not suffer unduly from the mediocre performance of that operation. (Note the expansion in the lower right-hand corner of “Three Paths of Entrepreneurial Expansion,” an expansion that was later reversed.)

Initially, the Promise entrepreneur, Ryoichi Jinnai, funded the company with local resources — namely, his own equity. Although it was clear early that the opportunity was, in fact, limited to Japan, resources were a different story. Japan’s main banks, under direction from the Japanese Ministry of Finance, preferred lending to industrial conglomerates — somewhat ironic, given that fast-growing Promise had a clear business model whereas the finances of many conglomerates were hardly transparent. Nevertheless, Promise was forced to seek out foreign banks as lenders. According to the CEO, as business grew, “It became easier for us to collect capital — in many cases, foreign capital as well — and we were able to expand dramatically.”14 Subsequent to its IPO in Japan in 1996, it also attracted substantial numbers of foreign shareholders. (Currently, more than 20% of its equity is held by foreigners, mostly institutional investors.)

Tensions abounded in the company’s off-diagonal expansion strategy. It had to communicate succinctly and in timely fashion with foreign lenders and equity holders, no small feat for an enterprise in which few senior employees spoke English or had international business experience. Had the company simultaneously expanded its opportunity across borders, the management team would probably have been more diverse and better prepared to deal with foreign resource providers. Jinnai also anticipated that funding from foreign sources could dry up quickly in the wake of local events that foreign investors might interpret more negatively than would local sources. That possibility of capital suddenly becoming scarce necessitated a transparent management accounting system and a clear contingency plan for how to carry on if foreign sources of debt capital did dry up. Currently, Promise is positioned in the lower right-hand corner of the international expansion matrix and doing very well, but industry observers suggest it may eventually also pursue cross-border opportunities.

The path through the upper left-hand corner also creates considerable tension. AirbizExpress is a leading provider of air-express services in Pakistan. It was started by an entrepreneur who, with modest local resources provided by his family, grew the business to $12 million and nearly 2,000 employees by reinvesting profits and exploiting capital-leasing contracts. Initially the company pursued only a domestic business opportunity but had to overcome a good deal of corrupt governmental practice. Pursuing a regional and eventually worldwide opportunity made sense not just because international air-express competitors had overlooked certain niches, but also because it had buffered the entrepreneur’s business and his personal risk in the uncertain home context.

Securing cross-border resources to pursue a cross-border opportunity proved impossible, however. Potential foreign financiers worried that capital invested in the company’s international expansion might be siphoned off in the company’s home country. The entrepreneur had no choice but to pursue a path of incremental international expansion financed by cash flow from his business at home. This slow expansion generated extreme tension within the company. The entrepreneur’s challenge was to determine how much capital he could devote to pursuing an international opportunity without jeopardizing the business at home. He also faced other challenges, such as the requirement to obtain permissions from authorities at home to export capital and to operate a cross-border business in his industry. Because he anticipated the tension, the entrepreneur was able to deal successfully with it.

Structuring Ventures Is the Key to Success

Every international expansion path has its own tensions, even a path in the zone of balanced international expansion, but tensions are typically larger the more a company deviates from the balanced zone. However, these tensions can be significantly mitigated, and the odds of success greatly improved, if entrepreneurs devote considerable forethought to the structure of their ventures.

The structure should be such that the sophistication of the resource providers and time horizon for providing the resources match the venture’s strategy. Investor patience and understanding of the nature of the opportunity become particularly important when things do not go as planned, which happens frequently. One entrepreneur who was studied could not initially raise local equity for a local opportunity but did succeed in raising capital from an international corporate investor. The entrepreneur rightly anticipated that the international investor might get cold feet quickly if things did not go as well as planned and might refuse further funding. This happens often with international investors: National borders can be psychological barriers in investors’ minds, particularly when things go wrong. To neutralize this potential problem, as soon as the entrepreneur achieved some initial success, he quickly raised additional capital from a local investor who had a better understanding of the local market, even though that capital was not yet needed. The company’s development took much longer than planned, but the local investor did not cut off funding and even convinced the international investor to endorse, at the board level, a slower growth strategy. In other words, by engaging both a foreign and a local investor, the entrepreneur mitigated a potential conflict with the former. This kind of structuring depends just as much on correctly anticipating the chemistry between investors as on drafting the right legal contract.

A company that plans to pursue a worldwide opportunity with local resources is generally well advised to rely on internally generated funds even if this entails slow growth. Worldwide opportunities are often much more costly to pursue than entrepreneurs anticipate. Disappointed local investors might withdraw support at just the wrong time. Also, entrepreneurs tend to be more careful spending funds that are internally generated than those that are externally sourced.

A company can mitigate to some degree the tension that results from financing cross-border opportunities with local resources by partnering with strong, reliable companies in the target country to gain access to other important resources, such as suppliers and management talent. Starbucks, for example, owns all of its U.S. stores but has, from its early days, partnered with local companies in most other countries.15 The structure of such cross-border joint ventures, of course, depends heavily on choosing the right local partner and forging contracts that provide for a clear exit by each partner and a fair distribution of returns.

Any company that experiences extreme tension during expansion, especially one using local resources to pursue a worldwide opportunity, is well advised to seek alternative funding quickly. Attracting cross-border resources to reduce tension as a company grows requires forward-looking behavior. The founders of Indian software giant Infosys Technologies Ltd. were pioneers with respect to transparency. Infosys was the first Indian company to follow U.S. generally accepted accounting principles and to distribute audited quarterly reports to its investors. These decisions made it easier for the company to raise capital in the U.S. stock market when management determined that further international expansion depended on a broader resource base than the Bombay Stock Exchange, where the company had previously been listed.

Even companies that expand along a balanced path, by simultaneously broadening the geographic range of opportunities and resources, are not immune to tensions. One such company, Georgian Glass and Mineral Water Co., in the Republic of Georgia, encountered a roadblock in its international expansion because of a weak home-country legal system that seemed powerless to settle claims. The company succeeded in attracting investment from the International Finance Corp., a member of the World Bank Group. IFC’s political influence helped the company achieve a speedy, favorable settlement of claims, which, in turn, enabled it to further expand internationally.

Tensions that occur as ventures expand across borders must be monitored carefully. Board members can play a particularly important role in this process by continually asking the entrepreneur and his team a range of questions about whether the expansion is progressing according to plan, whether adequate contingency plans are in place, whether the pace of expansion should be slowed or accelerated, and so on.

Board members should insist that corrections in a company’s international expansion plan are made sooner rather than later. Entrepreneurs can develop tunnel vision and are often late to adapt, scale back or accelerate international expansion efforts. This can severely affect employee morale, growth prospects and the overall financial health of the venture.

Because entrepreneurs are contemplating international expansion earlier than ever in the lives of their ventures, they would be well advised to do their homework and not be forced into reactive mode when problems and tensions arise. Although it is in the entrepreneurial nature to plunge ahead, the implications of doing business across borders can be explored with the international expansion matrix even before a venture is embarked upon. That analysis could determine the right structure for the venture — one that anticipates and mitigates growing pains and makes the difference between success and failure.

References

1. Several researchers have recently examined theoretical and empirical aspects of young firms that expand abroad. These researchers have found that traditional models of internationalization, namely stage-oriented models, do not fit the new empirical evidence well and that firms in high-technology industries in particular expand early in their lives. See for example: P.P. McDougall, S. Shane and B.M. Oviatt, “Explaining the Formation of International Ventures: The Limits of Theories From International Business Research,” Journal of Business Venturing 9 (1994): 469–487; and R.C. Shrader, B.M. Oviatt and P.P. McDougall, “How New Ventures Exploit Trade-Offs Among International Risk Factors: Lessons for the Accelerated Internationalization of the 21st Century,” Academy of Management Journal 43, no. 6 (2000): 1227–1247.

2. Many costs of doing business on an international scale have decreased substantially over the years. For example, a three-minute telephone call from New York City to London cost $717.70 in 1927 and 84 cents in 1999 (all in 1999 U.S. dollars). Shipping a 150-pound parcel by air from New York City to Hong Kong cost $2,188 in 1960 and $389 in 1999 (in 1999 U.S. dollars). Even more dramatic, transporting a container via ship from Los Angeles to Hong Kong cost $10,268 in 1970 and a mere $1,900 in 1999 (in 1999 U.S. dollars). Domestic communication and transportation rates also have decreased, but relatively less than did cross-border rates. See “Air Cargo” (Washington, D.C.: Air Traffic Conference of America, 1961), 58; “Air Cargo” (Washington, D.C.: Air Traffic Conference of America, 2000), 32; “Statistical Abstract of the United States” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of Census, 1929), 153; “Statistical Abstract of the United States” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001), 716; “Containerized Cargo Statistics” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, Maritime Administration, Office of Trade Studies and Statistics, February 1971), 57; and “Containerized Cargo Statistics” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, Maritime Administration, Office of Trade Studies and Statistics, January 2000), 164. (The 1999 U.S. dollar figures for earlier years were calculated by Research Services, Harvard Business School.)

3. A recent paper finds that there is an initial liability of foreignness. When small and midsize firms first invested in subsidiaries abroad, their profitability declined. With increasing foreign direct investment, profitability then increased. See J.W. Lu and P.W. Beamish, “The Internationalization and Performance of SMEs,” Strategic Management Journal 22, no. 6/7 (2001): 565–586. Another recent paper finds that prior marketing, new-venture and international experience by the top management team of a venture was positively correlated with the share of sales a venture generated abroad. R.C. Shrader, B.M. Oviatt and P.P. McDougall, “How New Ventures Exploit Trade-Offs Among International Risk Factors: Lessons for the Accelerated Internationalization of the 21st Century,” Academy of Management Journal 43, no. 6 (2000): 1227–1247. A third paper also finds a positive relationship between the international experience of young firms and their performance. S.A. Zahra, D.R. Ireland and M.A. Hitt, “International Expansion by New Venture Firms: International Diversity, Mode of Entry, Technological Learning, and Performance,” Academy of Management Journal 43, no. 5 (2000): 925–950.

4. Two recent papers highlight the positive role of networks on entrepreneurial activity. See A. Saxenian, “The Role of Immigrant Entrepreneurs in New Venture Creation,” in “The Entrepreneurship Dynamic,” eds. C.B. Schoonhoven and E. Romanelli (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press: 2001); and O. Sorenson and T.E. Stuart, “Syndication Networks and the Spatial Distribution of Venture Capital Investments,” American Journal of Sociology 106, no. 6 (May 2001): 1546–1589.

5. H.H. Stevenson and D.E. Gumpert, “The Heart of Entrepreneurship,” Harvard Business Review 63, no. 2 (March–April 1985): 85–94.

6. I define entrepreneurship as opportunity-driven behavior cognizant of the resources required to pursue the opportunity. The kernel of entrepreneurship is to identify a potential opportunity, match the opportunity and resources optimally, and keep adjusting that match as the opportunity materializes. Opportunities and resources are thus intertwined, and entrepreneurs must be mindful of constraints on access to resources. Stevenson defines entrepreneurship as “the pursuit of opportunity without regard to resources currently controlled.” He developed his definition mainly from the study of U.S. ventures, while I developed my definition from the study of a broad range of ventures domiciled in more than 20 countries. Though both of our definitions include opportunities and resources, mine suggests a closer connection between the two.

7. W. Kuemmerle, “Home Base and Knowledge Management in International Ventures,” Journal of Business Venturing 17 (2002): 99–122.

8. The challenges of international expansion have much to do with geographic distance. See P. Ghemawat, “Distance Still Matters: The Hard Reality of Global Expansion,” Harvard Business Review 79 (September 2001): 137–147. If a startup firm expands into a country that is geographically close, it will typically have an easier time being successful there. Cultural differences are often less significant in neighboring countries, and travel distances are short enough to accommodate frequent visits to new subsidiaries, especially during the critical early days. For this reason, it makes sense to think of international expansion along a continuum that includes a distinct intermediate category of “regional” expansion, a category somewhere between a purely local business and one that operates in all countries around the world. Firms that expand regionally will typically set up a small number of subsidiaries in neighboring countries.

9. The concept of the international expansion matrix was in part inspired by the product-process matrix developed by Robert H. Hayes and Steven C. Wheelwright. Their matrix juxtaposes manufacturing process structures and product life-cycle stages. They argue that most manufacturers are positioned along a diagonal because there is a natural fit between certain manufacturing processes and product life-cycle stages. See R.H. Hayes and S.C. Wheelwright, “Link Manufacturing Process and Product Life Cycles,” Harvard Business Review 57, no. 1 (January–February 1979): 1–9.

10. See E. Malmsten, E. Portanger and C. Drazin, “Boo Hoo — $135 million, 18 months ... a Dot.com Story From Concept to Catastrophe” (London: Arrow Publishing, 2002); and G.J. Stockport, G. Kunnath and R. Sedick, “Boo.com — The Path to Failure,” Journal of Interactive Marketing 14, no. 4 (2001): 56–70.

11. W. Kuemmerle, “Case Studies in International Entrepreneurship: Managing and Financing Ventures in the Global Economy” (Burr Ridge, Illinois: McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2005), 60.

12. Ibid., 81.

13. Ibid., 273.

14. Ibid., 446.

15. Starbucks made its first foray into a foreign country through a joint venture in Japan in 1996. Starbucks now has joint ventures with local partners in most countries where it operates outside the United States. One notable exception is the United Kingdom, where Starbucks acquired an existing coffeehouse chain in 1998 and expanded from that base. See N. Koehn, “Brand New: How Entrepreneurs Earned Consumers’ Trust From Wedgwood to Dell” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2001), 253. Other countries where Starbucks owns its stores are Australia, Canada and Thailand.