Unlocking the Business Potential of Virtual Worlds

Virtual worlds have been slow to catch on in businesses — but employees familiar with the technology may help.

Topics

Social Business

Image courtesy of Flickr user John E. Lester.

For businesses, virtual worlds — computer-simulated environments in which individuals interact with one another via avatars representing their digital selves — offer a collaborative tool that has a number of possible uses, from saving money on travel and conference expenses to employee training. But despite virtual worlds’ organizational potential, their workplace usage is still low, and a number of initial attempts by companies to establish a presence in virtual worlds met with failure. The challenge for longer-term virtual world adoption by corporations lies in clearly demonstrating the technology’s business value to the organization. That business value will vary across organizations — and organizations need to find out for themselves what virtual worlds can do for them. One way to do so is through employees who are already familiar with the technology.

There are many types of virtual worlds. To make sense of the numerous platforms that exist, it is useful to visualize a continuum of virtual worlds with virtual worlds for recreational use — such as massively multiplayer online games like World of Warcraft and Guild Wars — on one end of the continuum and business-oriented, immersive environments — such as ProtoSphere and Teleplace — on the other. Somewhere in between are mixed-use virtual worlds such as ActiveWorlds and Second Life.

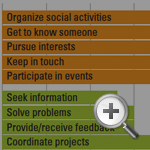

We argue that managers can better identify the potential business value of virtual worlds by taking advantage of some employees’ engagement with this technology outside the workplace. To provide insights for organizations on virtual world use, we surveyed more than 200 early virtual world adopters, whom we reached through an invitation to participate in the study that was sent to 700 members of a large online community of virtual worlds users. Two hundred three usable questionnaires (for a final response rate of 29%) were obtained and used for hypothesis testing. Seventy percent of the respondents were male, and respondents’ median tenure with their current employer was three to four years. The median age group was 40 to 49. Thirty percent of survey respondents had a business background, 17% had a computer science or engineering background, 13% had a social sciences background and 13% had a humanities background. Eighty-eight percent of the respondents had a bachelor’s or higher degree; 60% held a managerial position. Survey respondents reported frequent use of virtual worlds not only for recreational uses but also for work uses such as brainstorming (48%) and project coordination (36%). (See “How Early Adopters Use Virtual Worlds for Play…and Work.”)

Our research indicated that these early adopters of virtual world technology tend to have a strong sense of information technology playfulness and a need for uniqueness. (IT playfulness refers to the degree of cognitive spontaneity in computer interactions, and need for uniqueness refers to a tendency to seek distinctiveness through adoption and use of symbolic products or innovations.) This characterization is in line with the gaming origin of virtual worlds and with the use of avatars, which can be customized by the user. Indeed, many respondents self-identified as having a strong need for uniqueness, which they fulfill via the use of emerging technologies. Respondents further indicated an inherent tendency to innovate with new technologies. Finally, respondents displayed a predisposition to use technologies creatively.

Our survey of these early adopters of virtual worlds revealed a strong link between the use of virtual worlds for entertainment and the identification of their usefulness for work. While utilitarian and recreational uses are distinct, it is not unimaginable that an individual who uses a virtual world for entertainment will explore and exploit its usefulness for work. This is especially true when the individual is satisfied with the performance of the virtual world for entertainment. Indeed, our survey results strongly indicate such a diffusion of virtual worlds use from the recreational to the workplace domain. In other words, our survey showed that those who currently use virtual worlds for entertainment — and are satisfied with the experience — are more likely to use them for work.

As one survey respondent, a marketing executive at a large international organization, put it, “[Our company’s] early adopters were mostly from a community of people who were involved in virtual worlds for play, saw the potential for using them for work and encouraged [our company] to explore this space.” Within organizations, such early adopters are also more likely to voluntarily assume the role of technological evangelists — that is, voluntary and enthusiastic champions whose support and motivation are critical for the widespread adoption of virtual worlds within the organization. The low-cost, low-risk strategy for companies is to identify such individuals within their own organizations and allow them to explore business applications for virtual worlds.