What the Media Is Really Telling You About Your Brand

By unpacking the idea of a good or bad reputation into a profile of what the media says about their company, executives and public relations managers can understand and then influence their corporate reputation — and with it, their company’s real performance.

Topics

An important but often overlooked aspect of executive leadership is the creation of a good corporate reputation and the use of this asset to enhance organizational performance. There is accumulating evidence that a company’s reputation influences both its operational and financial performance.1 Because corporate reputations reside in the heads of people rather than as tangible assets, one of the key factors determining the various reputations of a company is the coverage it receives in the media.2 The power of the media comes from its reach and prominence, its role in certifying some companies as legitimate and important players in the market and people’s beliefs that it has superior access to information and expertise in evaluating companies. In this way, what the media says has a real impact on the business fortunes of companies.

Over time, media coverage defines what is important for people to believe about companies and what aspects of their character and performance should be used to evaluate them. These parameters form the basis of a company’s reputation presented by the media. However, the sheer volume of media information circulating about so many companies makes it difficult to summarize this coverage and present a meaningful profile of an organization’s media reputation. To help with this task, a corporate ratings industry has emerged that produces public scorecards of business performance. More than 50 different scorecards of corporate reputations are published in print media around the world.3 Many companies track the overall tone of their media coverage, but relatively few analyze the basis of the coverage to inform executives about the drivers of their company’s media reputation. More typically, executives simply accept the factors used in corporate scorecards as the key aspects of their reputation profile. The ratings agencies that compile scorecards also select a set of peer companies for evaluation. More often than not, these are a disparate collection of well-known companies rather than a set of industry competitors. Thus, it is not surprising that many executives consider scorecard rankings of corporate reputation to be little more than beauty contests.

To help overcome the frustration of many senior managers with reputation rankings, this article outlines two related techniques for assessing media coverage: (1) profiling the media communication about a company’s actions and its products and services, which enables executives to gain a clear understanding of their organization’s media image (what is said) and reputation (whether this is good or bad) and (2) the use of a more descriptive type of language in explaining the various facets of an organization’s media reputation profile, which can inform remedial action in a way that the opinion poll-style reputation ranking systems cannot. (See “About the Research.”)

What You Measure Matters

At the heart of any measure of performance are some assumptions about exactly what is being measured. For example, what does it mean to be one of America’s most admired companies? According to Fortune magazine, which has produced such a measure since 1984, it means that the company scored well on eight attributes ranging from financial soundness to management quality to community and environmental friendliness.4 These are the principal drivers of admiration in this widely publicized rating. A more critical assumption, however, is that admiration is a key factor that both financial analysts and senior executives use to evaluate a company — because these are the two groups that Fortune polls for their opinions.

A reputation scorecard measure requires that someone develop a list of attributes for people to rate. This list is usually based on a review of published research (for the most admired companies list, theories about admiration, respect and reputation) and intuition (whatever else the researchers think is important). There is also the aggregation method — that is, how the individual scores will be combined. In the Fortune example, they are simply added up, which gives equal weight to each attribute.

Because the media are eager to publish and support lists of best and worst companies, these scorecards will persist. Journalists like to use scorecards as corroborating evidence for their stories about corporate performance. Academics also have found these measures of reputation useful in their search for relationships between different aspects of reputation (such as corporate social responsibility) and performance (such as the quality of stakeholder relationships). However, because of the way that most scorecard rankings are designed, they have limited value for executives wishing to understand how a particular issue might affect their company’s reputation among different groups. This limitation is most acute in times of crisis, at new product introductions and during major changes in strategy. Nonetheless, scorecards are useful for measuring the overall sentiment of a crowd of independent people who hold their own private opinions. When a company falls in these polls, it is often a sign of impending reputation trouble.

There is, however, a very different way to measure admiration and corporate reputation: by listening to how people and journalists talk about a company and examining the specific words and phrases they use to describe and evaluate it. For example, U.S. citizens have characterized their strongest brands with such phrases as “taint-free reputation,” “instantly recognizable,” “cares about its reputation and customers” and “satisfactory experience reinforced by advertising.”5 Descriptions such as these can be analyzed to reveal the themes and contradictions in what people say. Because the attributes people use are the ones that have real meaning to them, the number of times an attribute is used in media articles to describe a company will be a good guide to its relative importance. Some of these attributes will fit nicely with current academic and managerial theories, but others will be new and therefore more insightful. For example, the last phrase above suggests that the role of advertising for a strong brand is to reinforce the brand experience rather than try to create it.

The shift in attention from a prescribed set of rating criteria to unscripted journalists’ perceptions (or beliefs) and evaluations allows media coverage to be interpreted in a way that is useful to line managers and those in the executive suite. It changes the topic of corporate reputation from “nice to know” (“We scored 73 out of a possible 100 and were ranked third best in our industry.”) to “need to know” (“On six out of eight attributes used to profile our company, we were equal to or better than our major competitors, but on the other two we need to make substantial improvement.”).

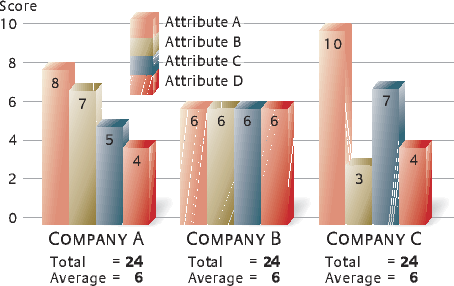

The first report offers a somewhat mysterious single-number summary of performance. The second report demands an explanation of which attributes were good and bad. In this way, it is much more discussable and accessible for scrutiny. To illustrate this point, consider the breakouts of three scorecard scores. (See “Similar Corporate Reputations but Different Profiles.”) While the three companies shown (A, B and C) get the same total score and would be tied in a corporate reputation ranking, they each have a very different profile of scores. Therefore, the management actions taken by the three companies should differ.

Profiling a company’s reputation in this way is like looking at its DNA sequence. This is a far more insightful method for diagnosing reputation risks and highlighting opportunities to exploit a good reputation than simply tracking scorecard totals. A company’s poor performance in one area can completely overshadow excellence in other areas.6 For example, research in Australia has shown that if a company is thought to mistreat its key stakeholders — namely, its employees and its customers —the company will have difficulty being taken seriously for the good things it is doing.7

How You Report What Is Measured Really Matters

Media profiling affords executives information they can use to assess the impact of reports on their company’s reputation and develop an effective response. Consider a stylized company profile derived from Cubit Media Research Pty. Ltd.’s analysis of media articles about a range of Australasian companies.

“Media salience” shows the prominence of a company’s media image, while “media tone” and “coverage breakout” outline different aspects of company reputation.8 This media profile is like the actual image of the company reflected back to managers in a mirror. Because the media image is seldom identical to the ideal self-image of the company, it can inform a useful debate about what needs to change. Executives can explore contradictions between what the company says about itself in external communications (the “we say” or “ad speak” of the company) and what is being reported to various stakeholders (what the media says or “street speak” about the company). Managers also can compare the relative amount and tone of coverage about their company versus peers or competitors.

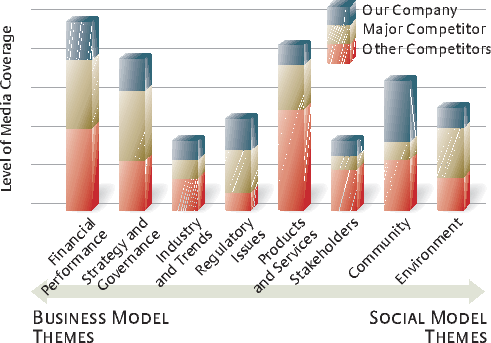

Media profiling typically examines companies across eight major message themes.9 These macrothemes range from a company’s business model, which is usually described in terms of “hard numbers” such as profit figures and market share, to its social model, which is often written about in terms of corporate behaviors such as social responsibility actions. Each message macrotheme is made up of many microthemes, such as profit and stock trends compared to expectations. Message themes are measured by counting the number of favorable and unfavorable comments made about a company over a period of time in specific media outlets and/or by particular journalists.

Media profiling documents how significantly companies may vary in the amount of coverage they receive. Analysis shows whether a company is “alive” in the media or “under the radar.” Furthermore, the relative prominence of various message themes reflects whether a company is viewed in multidimensional terms or defined by relatively few themes. (See “Media Salience”) The positive or negative tenor of media coverage is best determined by plotting the distribution (rather than a net score) of comments both across a peer set of companies and across message themes. (See “Overall Media Tone” and “Coverage Breakout.”)

To illustrate these insights, consider a story about Apple Inc. recently published in BusinessWeek, titled “A Bruise or Two on Apple’s Reputation.”10 The article contains several elements:

- BusinessWeek story line. “Is the company’s stellar service keeping up with its hypergrowth? Some customers don’t think so.”

- Journalists’ themes. As Apple’s new products (iPod and iPhone) become more successful, they are being purchased by customers who are less devoted to Apple and who are often less tech-savvy. “The vitriol of complaints on some Apple-related blogs and Web sites…is approaching that usually reserved for cable TV.” Positive endorsement from a longtime customer, negative endorsements from two new customers accompanied by their forlorn photos.

- Apple’s position. Timothy D. Cook, Apple’s COO, claims that an array of internal metrics shows service has never been better.

- Contradictions. Cook versus the two new customers and the blogs. Cook versus an academic expert who endorses the claim that as the customer base becomes more diverse, it becomes harder to satisfy.

- Comparisons. “Even small cracks in a pristine reputation … can be a sign of larger problems. Just ask Dell.” Table of customer satisfaction scores from an independent research firm shows Apple down (79% from 83%), Hewlett-Packard up (76% from 75%), Gateway up (75% from 73%) and Dell down (74% from 78%).

The rich content of this three-page article is lost if it is classified as either a mostly positive or mostly negative piece. However, if the article is examined through a multifocal lens, several topics become apparent: strategic issues (market expansion), industry problems (all competitors have customer satisfaction scores around 75%), and product and service issues (new multifunction products make it harder for customers and company service representatives to get these products to work). There is also conflict — Apple’s COO contradicting the journalists’ evidence.

One of the key advantages of media profiling for company management is that it visually shows several aspects of corporate reputation at a glance: salience of media coverage, strengths and weaknesses of company performance affecting reputation and media confusion. For example:

- Like all major companies, Apple has a public relations group tasked with creating a positive image for their company. However, as the BusinessWeek article demonstrates, building media salience often comes at the cost of having journalists set the tone and themes of the company’s profile.

- When media message themes are largely negative, this can signal real trouble with a company’s products or services. Negative messages can be direct (such as reporting an outright decline in service quality) or indirect (such as noting how the popularity of Apple’s new products is causing a strain on customer service).

- Media coverage affects multiple stakeholders. The BusinessWeek article is a classic “you say” versus “we say” account that requires a careful response from both Apple’s PR and human resources groups — the former for external stakeholders, the latter for internal stakeholders. Employees are bound to notice this article, and it will raise concerns about the company’s ability to deliver the service expected by customers. Thus, the article calls for a clear response from COO Timothy Cook to employees about the facts in the article (such as why there is a difference of opinion) and what Apple intends to do about service delivery. Responses must be tailored to the specific concerns of different parties.

Using Media Profiling to Inform Executive Decision Making

Media profiling immediately creates a discussion that informs management action. It does this by unpacking each macro-theme (such as Apple’s service quality) into the microthemes that a journalist uses to discuss it (for example, the more diverse Apple’s customers become, the harder they are to serve). Focusing on microthemes quickly moves the discussion beyond simple statements like “We have a good (or bad) reputation” to more complex and meaningful statements such as “Although our products are regarded as good, our reputation for service, while generally good among our long-term customers, is problematic with our new customers.” This change of language is important because people seldom unconditionally like or dislike a company (or a person).

A more expansive language about corporate reputation also makes it easier for executives and PR people to link a company’s media profile to its broader “reputation story” that speaks about mission, morality and modes of operation.11 This linkage can have two related positive effects. The first is that a corporate story based on key reputation attributes helps to personalize and soften what can seem a faceless and impersonal firm. In this way, the company can trade on the fact that it has a reputation for being good at specific things. For example, 3M Co. for decades has been supporting its reputation for innovation with the corporate brand slogan “Innovation” (recently updated as “the Spirit of Innovation”) and numerous stories within the company about its innovative endeavors (such as the invention of the Post-it Note). In effect, reputation stories put the various facets of media coverage in the “Coverage Breakout” chart into perspective. The second positive outcome of a story-based explanation of reputation is that this is often more interesting to journalists and their audiences than any array of facts and figures. The power of storytelling in a corporate setting has been well established.12 Thus, there is a greater likelihood that companies can gain the attention of journalists and keep them “on message.”

Managers assessing media profiles will find it useful to calibrate their company against some relevant benchmarks. In many industries, there are accepted behaviors and standards of performance that define what is called the organizational field.13 For example, in consumer electronics, new products are a regular feature, and many business journalists focus their attention first on whether the company has a steady stream of these and then, when a new product is launched, on its likely success and impact on financial performance. Within this discussion, new-product microthemes such as new features, quality, relative advantage, target customers, competitors and price are discussed. In contrast, articles in the “weekend media” tend to focus more on a product’s “lifestyle effects” on people. In another example, our research has found that in beverage industries, prominent message themes are product quality, value and the social impact of products. In telecommunications, the focus is often on the company’s strategy and the quality and value of the service offered.

Another relevant benchmark for many companies is the risk profile of the media coverage. A company that is receiving very negative or very mixed (positive and negative) coverage across a number of message macrothemes may be heading for trouble. In the field of word-of-mouth or viral marketing, it is thought that negative commentary is often more damaging than the boost provided by positive commentary — a point made by the authors of the BusinessWeek story on Apple noted earlier. Another signal of trouble is negative media commentary about key stakeholder groups. For example, stories about disgruntled customers or disaffected employees can infect other customers and employees by challenging some of their positive beliefs about the company. And, as noted earlier, when people think that a company treats these two groups poorly, they tend to discount its good deeds in other areas.14

Sometimes media discussions will not reflect the desired market position for a company or its products. For example, a technology company that we studied promoted the functionally oriented, innovative features of its product, but journalists focused on the product’s styling. This is an instance of particular journalists using their own mental models of what is important for success in an industry to frame their discussions. When managers understand these mental models, it not only helps them counter uninformed media coverage, it also enables them to interpret how their company is performing relative to these industry-defining attributes. And because the media shape the environment in which a company’s advertising is evaluated, communication themes that run counter to, or are simply independent of, those used by journalists can reduce the impact of this advertising.15

When journalists focus on strategy and governance, one message microtheme that has proven troublesome for many companies is the profile of the CEO. In some countries, charismatic leadership is a positive theme, while in others it is tainted with celebrity. In either case, when high-profile leaders are called to account by journalists, the CEO’s reputation in the eyes of key stakeholder groups — especially employees — can be damaged. To check these potential effects will require corroboration with other stakeholder-based measures, such as the trust and engagement of employees and loyalty of customers.

When companies in an industry are profiled together, it is easy to see the “agenda” that journalists are pursuing reflected in the dominant message themes. It is also easy to see the salient companies that stand above their competitors. The media play a powerful role here; who they select for attention and what they say puts these companies’ reputations in play. For example, because of intense and sustained media focus, many people around the world instantly associate corporate misbehavior with Enron Corp., which crashed so spectacularly in 2001. Enron is certainly not the only corporate wrongdoer, but it is one of the most famous because of its media coverage.

After creating media profiles for their companies, how should managers respond to various scenarios?

First, seek to protect and enhance the company’s good message themes. These strengths can be leveraged by linking them to other important message macrothemes. One way to accomplish this is to show how the good themes complement other important messages within the context of the company’s overall reputation story. For example, General Electric Co., long known for its strong emphasis on profit, has not had a good reputation for its environmental awareness. Now, however, the company’s current “ecomagination” story, publicized as “innovation for sustainability,” is challenging people to reevaluate their opinion of the company with respect to its “green” footprint. By setting specific financial targets for the company’s more environmentally friendly products, GE is linking its already strong “profit story” to its emerging “environment story.” This attempt to create leverage effects also fulfils an important PR need: filling a communication vacuum that invites journalists to criticize the company or encourages the public to believe that the company isn’t doing anything on environmental issues.

Second, address negative message themes head-on. Three courses of action can be considered for negative message macro-themes. One is to fix the problem that is causing the negative press. What needs to be changed most likely will be revealed by one or more microthemes written about in the press. If the problem can’t be fixed straight away, then plan what needs to be done and communicate this to employees and the media. If a negative message theme is the result of a misconception, seek to correct this by providing new information to the media, perhaps briefing selected journalists. Only as a last resort should executives consider arguing against the negative message. Communications professionals recommend denial only when managers are completely sure that they are in the right and that they are being unfairly treated.16

For mixed message themes, seek to understand both sides of the story. When media coverage has both positive and negative attributes, it suggests either mixed messaging by the company or differing schools of media thought about an issue. An example is positive financial performance that is presented as weaker than expected. Although a company seeks to promote positive themes, executives must first fully understand negative aspects. These will be found in the differing sets of message microthemes appearing in the media. Scrutiny of these will reveal whether the issue is a journalist’s contradiction of the company or inconsistent messages running in parallel. When some media message themes are largely positive and others neutral, leverage effects of company activities may not be operative. For example, if a company’s substantial environmental efforts are not reflected in a coverage breakout analysis, it suggests that the efforts are not supporting the company’s products and services.17

Consider whether a missing message theme is really important. For example, does an absence of media attention about a company’s environmental activities really matter to a company’s critical stakeholders? While corporate social responsibility is currently a topic of interest to many in the media, it is often not of similar interest to consumers unless they can see how it directly improves a company’s products and services.18

In summary, from an organizational perspective, it is not possible to understand the commercial world and a company’s part in it without knowing what the media is leading people to think about the company and its competitors. One important way to focus this inquiry is to profile the media reputations of the industry participants. To get the most value from this scrutiny, it is necessary to unpack the idea of a good or bad reputation into a media profile of what is said about the company by the editorial opinion-shapers — arguably the most influential force in business communication. Media profiles of macro- and microthemes typically show that a company has a better reputation for some things than others. To benefit from this insight requires the use of a more complex language among managers about reputation, which can then motivate a discussion that directly informs management action.

References

1. For an overview of how corporate reputation influences operational performance, see G.R. Dowling, “How Good Corporate Reputations Create Corporate Value,” Corporate Reputation Review 9, no. 2 (2006): 134-143; and for an example of how good reputations influence financial performance, see P.W. Roberts and G.R. Dowling, “Corporate Reputation and Sustained Superior Financial Performance,” Strategic Management Journal 23 (2002): 1077-1093.

2. S. Lewis, “Measuring Corporate Reputation,” Corporate Communications 6, no. 1 (2001): 31-35; S.L. Wartick, “The Relationship Between Intense Media Exposure and Change in Corporate Reputation,” Business & Society 31 (June 1992): 33-49; C.J. Fombrun and C.B.M. van Riel, “Fame & Fortune” (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, 2004); T. Wry, D.L. Deephouse and G. McNamara, “Substantive and Evaluative Media Reputations Among and Within Cognitive Strategic Groups,” Corporate Reputation Review 9, no. 4 (2006): 225-242; R.G. Eccles, S.C. Newquist and R. Schatz, “Reputation and Its Risks,” Harvard Business Review 85, no. 2 (February 2007): 104-114.

3. Reputation Institute, “List of Lists: A Compilation of International Corporate Ratings,” fall 2007, www.reputationinstitute.com.

4. Fortune magazine’s evaluation for its “Most Admired Companies” list is based on scores concerning eight corporate attributes: asset use, community and environmental friendliness, ability to develop and keep key people, financial soundness, degree of innovativeness, investment value, management quality and product quality. The people who rate the companies are financial analysts, senior executives and outside directors of Fortune 1000 companies (other than their own).

5. J. Berg, J. Matthews and C. O’Hare, “Measuring Brand Health to Improve Top-Line Growth,” MIT Sloan Management Review 49, no.1 (fall 2007): 61-68.

6. Lewis, “Corporate Reputation.”

7. D. Porritt, “The Reputational Failure of Financial Success: The ‘Bottom Line Backlash’ Effect,” Corporate Reputation Review 8, no. 3 (October 2005): 198-213.

8. An alternate method of analyzing media coverage is counting media stories and assessing whether the coverage was essentially positive or negative. See Eccles, Newquist and Schatz, “Reputation.”

9. While message themes can vary depending on the particular circumstances facing the company, the typical themes are those shown in “Media Salience.”

10. L. Lee and P. Burrows, “A Bruise or Two on Apple’s Reputation,” BusinessWeek, Oct. 22, 2007, 81-83.

11. G.R. Dowling, “Corporate Reputation Stories,” California Management Review 49, no. 1 (2006): 82-100.

12. S. Denning, “The Leader’s Guide to Storytelling” (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2005).

13. L. Wedlin, “The Role of Rankings in Codifying a Business School Template: Classifications, Diffusion and Mediated Isomorphism in Organizational Fields,” European Management Review 4 (2007): 24-39.

14. Another early warning signal of reputation trouble is when employees dislike the companies they work for. Employee “engagement” surveys often are used to calibrate these effects.

15. A. Ries and L. Ries, “The Fall of Advertising and the Rise of PR” (New York: HarperBusiness, 2002).

16. J.R. Rossiter and S. Bellman, “Marketing Communications: Theory and Practice” (Frenchs Forest, New South Wales, Australia: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005).

17. General Electric’s “ecomagination” communication campaign is an example of a program designed to foster leverage effects.

18. T.M. Devinney, P. Auger, G. Eckhardt and T. Birtchnell, “The Other CSR,” Stanford Social Innovation Review (fall 2006): 30-37.