Beyond Better Products: Capturing Value in Customer Interactions

Topics

Talk to the senior executives of any progressive company today and they will tell you about its huge investments in innovation, bulging new-product pipelines, proprietary technologies and relentless drive to shrink time to market. They’ll also admit that these efforts have not helped them outrun the competition. Although businesses are moving faster than ever, competitors are constantly nipping at their heels, emulating new products, replicating entire product-development systems and processes, and keeping pace on the same treadmill. New products may generate hefty returns, but the advantage is short-lived. These days, a company’s rivals are likely to be world-class sprinters.

Eroding competitive leads are the result of forces that are equalizing companies’ ability to innovate: the increasingly rapid and free flow of information and knowledge, the movement to global standards and the advent of open markets for components and technologies. Today, a company such as Handspring can appear and, within a few months, launch a hand-held organizer similar to the Palm Pilot in design, functionality and performance. Thanks to open markets and open standards, Handspring has access to the same product designers and manufacturers that Palm uses.

This example is not the exception, and it raises profound questions about the sources of sustainable competitive advantage. If product parity is relatively easily achieved in today’s world, customers will turn to new criteria when deciding to buy one company’s products over another’s. We have attempted to establish the nature of these criteria over the past three years by collecting data from more than 1,500 senior executives in interviews and group discussions. In particular, we have focused on this question: “Why do your customers choose to buy from you rather than from your competition?” (See “About the Research.”)

Despite the vast range of industries represented by the executives, their responses were remarkably similar. They agreed almost universally that offering great products, technologies or services is merely an entry stake into the competitive arena. Most spoke of the need to maintain an edge in the way their companies interact with customers; that is, they recognized that customers often value how they interact with their suppliers as much as or more than what they actually buy. As the main drivers of customer choice, the executives cited cost-oriented factors like convenience, ease of doing business and product support, as well as risk-oriented factors like trust, confidence and the strength of relationships.

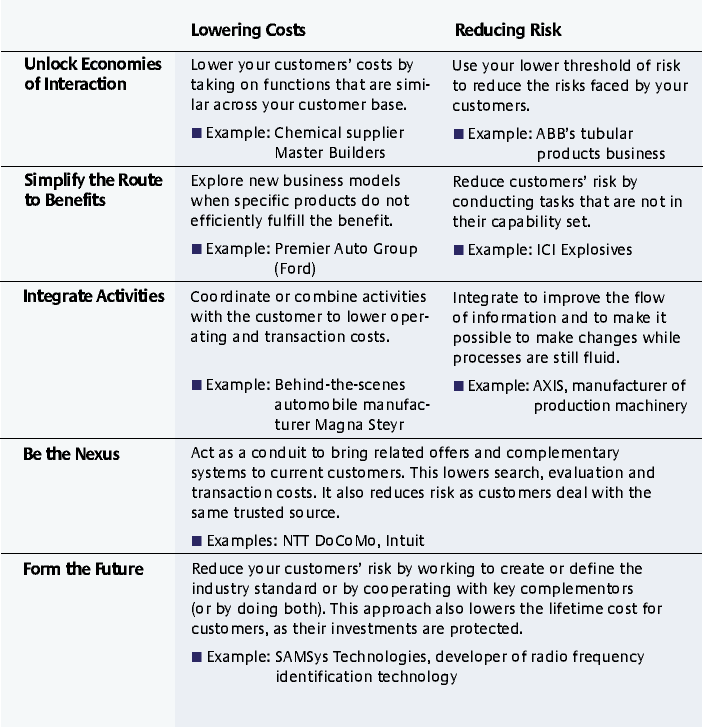

Although many managers realize the need to pay attention to cost and risk factors that influence customer choice, our research data indicate that companies are usually at a loss when it comes to translating this conceptual understanding into practice. We did find counterexamples, however: companies that are using one of five strategies to build competitive advantage through their approach to customers. (For a quick overview that also gives a sense of the range of companies involved in our research, see the table “Five Strategies for Building Advantage with Customers.”) These strategies are not easy to devise or implement; they require creativity, imagination, hard work (inevitably) and a willingness to take risks. But as we’ll demonstrate, strategy by strategy, the rewards are more than worth the effort. Before we turn to the strategies, we’ll take a closer look at how perceptions of cost and risk affect customers.

Manipulating the Levers of Cost and Risk

When product improvements can be matched quickly by competitors, companies have only two remaining levers available to influence purchase decisions: They can reduce customers’ interaction costs or make the purchase and subsequent product ownership a less risky proposition. Fortunately, these levers provide enormous and largely untapped potential to increase the gain that customers expect from a transaction.

Start with the issue of lowering costs. A buyer incurs a variety of costs in the course of learning about a seller’s products and services, acquiring them, using them and finally disposing of them. In addition, to extract value from the product, the buyer must configure the product to his or her needs. That can be as simple as chilling a beer before drinking it and as complex as integrating a new organizationwide software system with the existing IT infrastructure. Finally, when a customer buys a product or service, he or she commits to a rigid seller-defined bundle and forgoes the benefits of other potential bundles available in the marketplace. For example, when someone buys a family minivan, he or she obtains roominess and comfort but can never, with that product, enjoy the psychological benefits that come from driving a convertible. Most companies never attend to such costs, but they are real. Managers who give thought to ways to reduce these interaction costs will likely uncover innovative ways of increasing customers’ gain.

In addition to the generally hidden costs that customers face when they try to decide on a supplier, buyers also take on considerable risk and uncertainty. They implicitly consider the range of possible outcomes from the interaction and the likelihood that such outcomes will occur. Can I trust the seller’s promises? Will the product perform as expected? Will I be able to implement it successfully? Will I lose money? Will the seller be around for repair and maintenance? When potential customers feel that the risk is high that their expectations will not be met, they quite naturally choose not to buy. Many companies have been in situations in which customers stick with the industry leader’s product even though their new product is either of superior quality or cheaper or both — in their calculus of risk, customers prefer to wait until the new offering has been clearly recognized as superior for some time before they make a switch. Of course, the buyer can engage in due diligence to address questions of risk, but due diligence costs time, effort and money — in other words, it raises the interaction costs. For customers, it is greatly preferable to buy from a trusted seller.

Some of the companies in our research have figured out creative ways to earn their customers’ trust. They’ve reconsidered exactly what it is they are selling, they’ve leveraged strengths to make customers’ lives easier, they’ve worked with other organizations to provide an optimal (and unique) bundle of products and so on. A review of the strategies they’ve followed can provide managers in almost any industry with new ways of thinking about building advantage with customers.

Unlock Economies of Interaction

All companies recognize the power of economies of scale, scope and experience in producing better or cheaper products. They should also recognize their ability to leverage those same economies in the process of interacting with customers. Consider that suppliers often have many interactions of the same type with different customers (scale), many interactions with the same customer (scope), and access to information that makes it easier for them to gauge the risks involved in an activity for a particular customer (experience). To increase their customers’ sense of expected gain from a transaction, companies can reconfigure their activities to lower buyers’ interaction costs and perceived risk. For example, a supplier may be able to identify tasks that its customers have in common and decide that it can perform them more cheaply or effectively. By taking responsibility for the tasks, suppliers can save their customers time and money and effectively lock them in.

Consider Master Builders’ recent launch of its MasterTrac system. Master Builders sells chemical admixtures that are used to improve the performance characteristics of concrete; its customers include concrete producers that have many locations and either a regional or national presence. Until the new system was put in place, managers at each of the producers’ locations independently ordered and maintained inventory of each type of additive to suit their local requirements. For Master Builders, this decentralized approach meant that it had to ship many small orders of different additives at infrequent intervals to geographically dispersed sites. The small shipments were not cost effective, and emergency shipments were often necessary when customers failed to anticipate their needs correctly.

To meet this challenge, Master Builders developed a remote tank-monitoring system for immediate and seamless inventory control. The MasterTrac system consists of additive storage tanks fitted with wireless sensors that, when queried, relay inventory information to a Web site accessible to both Master Builders and the customer. Using that information, Master Builders was able to effectively manage inventory levels at individual locations on nearly a just-in-time basis. Under the new system, the customer realizes major savings from reduced inventory financing, reduced order and payment processing, and reduced inventory management time. Competitors that seek to win over the customer now face a much harder task.

Suppliers may also gain a sustainable advantage by reducing their customers’ risk, especially if they leverage their experience and reach. Asea Brown Boveri found a way to do that in its tubular products business. ABB supplies drilling pipe to ocean-based oil- and gas-drilling rigs around the world. As wells are drilled, pipe is threaded together and placed down the well. Although the product requires some technological know-how to manufacture, it is basically a pipe with threading welded onto it. In 1999, ABB was the world leader in this market but was facing increased competition from low-cost welding shops.

Since oil rigs can be located anywhere in the world (from Siberia to Vietnam to Chile), the industry convention was to price the product at the factory gate. Drilling companies would then take ownership and arrange to have the product delivered to the rigs. Their headaches began at this point since delays in getting the pipe to the drilling site were very expensive: Rental prices for an ocean-going drilling rig are $150,000 per day. Although the threat of delays was not ABB’s problem per se, the company recognized an opportunity to shift the terms of the business away from cost.

ABB’s managers knew that the greatest obstacle to on-time delivery was in getting through the importation and customs procedures of the country where the drilling site was located. ABB was uniquely positioned to take on that task for its customers. Because of its many business units in various industries, the company had a well-established presence in more than 100 countries, and its oil and gas unit understood the import regulations worldwide for the drilling business. For some key customers, ABB began offering contracts for drilling pipe that included delivery to a rig — with guaranteed delivery times. It essentially took on the risk of customs and importation delays. Even though ABB charged for these deliveries at cost, the increased value to the customer in terms of lower risk was much more significant.

Over time, ABB’s position as the market leader solidified because competitors lacked the global reach and expertise required to offer contracts that guaranteed delivery. ABB succeeded by looking at its interaction pattern with customers in all its businesses and finding an area where its risk was lower than that of its customers and competitors. ABB’s product hasn’t changed, but the new way of offering it has increased its customers’ expected gain from their purchases.

Simplify the Route to Benefits

It’s a given that companies must offer high-quality products if they want to succeed. It’s also a given that the products themselves, even when they’re very good, rarely provide all the benefits that customers are looking for. They must be combined with other elements before customers can realize their full value. The trick for companies is to redefine their offerings in ways that make it easy for customers to get the benefits they seek.

The Australian division of ICI Explosives took an innovative approach to helping its customers reap the benefits of one of the most unglamorous products imaginable: pieces of rock. ICI, like its competitors, had long sold commodity explosives to quarries. The quarries used these explosives to blast solid rock into aggregates of equal size. The customers’ challenge is to turn the rock face into a product that can be sold; an ineffective blast will yield large chunks of rock that are much harder to break down. As such, designing a successful blast requires considerable expertise and has a major effect on profitability. As many as 20 parameters affect the performance of the blast, including the profile of the rock face, the depth and diameter of the drill holes, and the weather. ICI, recognizing the risk that customers face, began a program to quantify what had previously been considered an art. Using computer models and experimentation, ICI engineers developed strategies and procedures that narrowed the uncertainty of blast performance. Instead of selling this new expertise as an added service, however, ICI began performing the blasts for the quarries and writing contracts for “broken rock.” Customers are now billed for the amount of broken rock of a size specified in the contract that is produced from a blast carried out by ICI.

The new contracts significantly reduce the business costs and risk faced by customers in two ways. First, they turn fixed costs (primarily quarry employees and drilling equipment) into variable ones and second, they set the performance of a blast at an acceptable minimum level. The customer pays only for the outcome, not for the commodity that goes into creating it. ICI is no longer simply a supplier of commodity explosives; it has become an integral part of its customers’ business. The redefinition of ICI’s role not only generated much higher margins for the business, it also gave ICI a much more defensible competitive position.

To create value beyond products, companies have to recognize that tangible goods are what they are: rigid, inflexible packages that impose an opportunity cost — the cost of forgoing alternatives — on the customer. Premier Auto Group, the luxury arm of Ford that manages brands such as Jaguar, Land Rover and Volvo, understands that its product offering may be too much of a constraint for its customers. The unit is preparing to offer a new kind of automobile customization that is based on usage. Customers will not purchase a car but rather a “mobility contract” from PAG that will allow them to use a sedan, a limousine, a sport utility vehicle or a convertible, depending on the customers’ needs. Redefining the offering in this way does not alter the fact that Ford will still make cars, but it changes how customers will buy and extract benefits from those cars.

Companies can systematically configure offerings that create value by simplifying the route to the benefits that customers seek. And suppliers can find a new source of competitive advantage if they can better perform certain tasks or better absorb related risks or costs than their customers can, all while producing the same benefits.

Integrate Activities

It’s not always feasible to take on particular customer tasks altogether. Companies can avoid the need to be wholly responsible by taking a collaborative approach — that is, by integrating various activities with their customers as a means of lowering risk and costs. The Internet has made such integration both possible and, by many accounts, essential. Suppliers must be prepared to offer an array of capabilities and resources that their customers can draw on as needed; both sides must be willing to integrate communications and form intercompany project teams.

A division of Magna International has integrated its activities with one of its major customers, DaimlerChrysler, to help the automobile giant meet its production needs. Magna International is one of the world’s largest and most diversified automobile parts suppliers; it has 166 manufacturing divisions and 31 product-development and engineering centers in 18 countries. Its initial success was driven largely by meeting the needs of automobile plants that it served through small factories located near its customers’ assembly operations. Radical changes in the automotive industry, however, have forced the company to change as well. Product and model life cycles have been drastically reduced; consumers are more fickle than ever; and competitors are aggressive in their pursuit of market share. Not surprisingly, demand for any given model of car is notoriously difficult to forecast, and automobile manufacturers need to be agile enough to respond rapidly to changes in the market.

To help manufacturers attain such operational flexibility, Magna International created Magna Steyr. This division is not merely an arms’ length parts supplier. Instead, the parent company has brought together all the capabilities required to engineer, design, produce and assemble entire vehicles. A few years ago, Magna Steyr was able to solve DaimlerChrysler’s enviable problem of excess demand for the Mercedes-Benz M-class sport utility vehicle. Magna Steyr had already been involved with DaimlerChrysler in the production of E-class Mercedes sedans and the Jeep Grand Cherokee and was accustomed to working closely with DaimlerChrysler engineers and regularly receiving information on demand forecasts. So when at the end of 1998 worldwide demand for the M-class SUV outstripped total capacity at DaimlerChrysler’s plant in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Magna Steyr was called in to provide backup. Within nine months, M-class SUVs were rolling off the Magna Steyr line in Graz, Austria. Magna Steyr’s integration with DaimlerChrysler was so seamless that the company might be confused for a division of DaimlerChrysler. Yet Magna Steyr has achieved this level of integration with each of its key customers, including BMW (for the X5 and X3 SUVs) and Audi (for the TT Roadster).

Having processes that are transparent to customers can have advantages for all involved, as a small Italian manufacturer recently demonstrated. AXIS specializes in the production of machinery for the manufacture of electric motors used in the automotive, domestic appliance, and power tool industries, and it has a reputation for quality and technical expertise. But in a mature and competitive industry, those strengths were proving insufficient. Customers like Black & Decker and Philips were increasingly concerned with their ability to reduce time to market and meet peak-season demand and were, as a result, turning a critical eye on their suppliers. In response, AXIS radically changed its approach to project management by opening up the entire process to its customers.

After AXIS’s managers had made that decision, a power tool manufacturer contracted with the company to supply a new production line for a nonstandard electric motor needed to make a new product. The first challenge was to fit the new line into the customer’s facility. Space was limited and labor costs were a concern, so the line had to be relatively compact and highly automated. Using a Web-based three-dimensional CAD system, AXIS worked with the customer’s engineers to optimize design concepts and help the customer create performance metrics under different operating circumstances and configurations. After the basic concept was agreed on, AXIS engineers designed the production line, sharing drawings, specifications and other data in real time with the customer’s engineers.

Midway through the design process, the customer’s engineers, seeing plans for a machine designed by AXIS, realized that the machine’s capabilities enabled them to develop a more efficient motor. An improvement on that order normally would have been integrated into the next version of the product, but now it could be built into the original design.

Once the production machinery design was completed and approved, the documents were sent to the production team and stored online in a folder open to everyone involved in the project. Later, as the production team began work on building the line, they realized that the engineers had been optimistic about the amount of work needed to construct one of the peripheral machines. To prevent triggering a slippage notice, they informed the designers in both organizations and referred them to drawings produced for an earlier project that might prove to be an adequate fix. The designers studied the drawings online and agreed on the changes. Production delays were minimized, and the customer was able to get the product to market on schedule. Documents from the production phase were also stored online and made accessible to in-field maintenance people in both companies.

The sharing of information and business-process integration at every step of the way were major factors in the customer’s successful launch of the new product. The customer enjoyed unprecedented control over the design and creation of the new production line and is likely to return to AXIS for related needs in the future.

Be the Nexus

A trusted supplier can turn itself into a market maker for many products and services that it doesn’t actually produce — and make money in the process. By being the link between customers and the sellers of complementary products and services, the supplier reduces buyers’ search and acquisition costs by “certifying” only qualified contacts. At the same time, the supplier increases the number of customer “touch points” and thus its claims on customer loyalty.

NTT DoCoMo is the nexus for many suppliers and customers that produce and use mobile Internet products and services. Its i-mode service, which had more than 28 million subscribers in early 2002, is by far the most successful mobile Internet service in the world. The foundation for i-mode’s success is DoCoMo’s coordination of all aspects of the mobile Internet experience: hardware, access, services and billing. Such coordination lowers interaction costs and risks for customers by making it easy to use the service while guaranteeing consistency.

In terms of hardware, for example, DoCoMo has worked closely with suppliers like Sony, Panasonic and Fujitsu to standardize i-mode handsets. The company has simplified access and use by building the service around a single portal that is available only through i-mode-enabled phones and by making it easy to navigate through 1,600 DoCoMo-certified sites from the portal. Web sites are keen to be endorsed by DoCoMo and are willing to adapt their offerings to DoCoMo standards for the privilege of being able to reach millions of users — who, in turn, get instant access to a critical mass of content and services. Finally, billing and payment are also easy with i-mode. Subscribers receive a single, itemized monthly bill, and because they get only one invoice from a trusted source, they are more apt to try new services than they would be through fixed-line Internet connections, where payment and verification are required for each site independently. By earning the trust needed to occupy the center of the mobile Internet, DoCoMo is offering value to hardware suppliers, content providers and millions of i-mode users. In the process, it is building an impressive competitive position for itself.

Intuit is another company that has leveraged its trusted position to become a nexus, in this case for small-business software applications. Intuit’s QuickBooks has an 85% share of the small-business-accounting software market and a 98% customer loyalty rating. But the more interesting story is how Intuit has been able to capitalize on its success with QuickBooks to capture an ever bigger share of small-business expenditures on information and data handling. Services such as QuickBooks Site Solutions (an Internet tool that enables small businesses to create a professional Internet presence) and QuickBooks Online Payroll have deepened its interaction with customers while reducing their risk and cost. And on an annualized basis, these new services generate four times and ten times more revenue per customer, respectively, than the original QuickBooks software.

More recently, Intuit has opened up access to the application-programming interfaces for the QuickBooks products. Third-party developers are now able to create software applications that are integrated into the QuickBooks platform. As a result, specific types of small businesses — architectural firms, medical groups and so on — can purchase customized solutions for applications, such as project billing or record keeping, while maintaining the same accounting core. Intuit’s move significantly reduces the small business’s cost of obtaining these solutions, since integration with its own internal procedures is guaranteed. The QuickBooks seal of approval also reduces the customer’s risk incurred in the selection of a new supplier or software. By allowing third-party developers to trade on its platform of trust, Intuit has placed itself at the nexus of suppliers and buyers in the industry.

Form the Future

Companies often have to collaborate with other organizations to help “form the future” — in other words, to shape businesses and products that will change the way commerce happens. This is especially true for new technologies in the networked economy, which are rarely the product of a single company. And what any business today has to realize is that the customer’s sense of risk is nowhere greater than when it is contemplating large cap-for any company developing a new technology, then, is to seek ways to lower the risks and costs from the early stages of product development onward — that is, even before a polished product is ready for a mass audience. Sometimes, as the story of SAMSys Technologies indicates, that even means giving up on your core product.

SAMSys is a small company with a radical vision for the future of radio frequency identification (RFID). The technology works like this: Objects are tagged with semiconductors that emit radio frequencies and can then communicate with one another and with people. The range of potential applications is staggering — for example, RFID could be used to inventory entire warehouses at the touch of a button or to get information about the contents of transport trucks and containers without opening them. A recent Accenture study found that RFID technology could save $70 billion in the supply chain by reducing inefficiencies in inventory carrying costs, shrinkage and labor. Despite its revolutionary potential, customer buy-in to RFID has been slow. The hesitation has been caused by the lack of universal frequency and protocol standards, as well as the rapid evolution of tag technology.

SAMSys was an early entrant in the RFID industry, and by 1998 it had developed a complete solution of tags and reader hardware. When the company realized that RFID adoption was slow relative to its potential, it moved to boost sales in the industry as a whole rather than focus on promoting its own solution. It recognized that customers would value a tag reader that was agnostic in terms of frequency and protocol so that they could invest in any RFID system without fear of incompatibility. To prevent obsolescence, the reader would also have to be easily upgraded with the appropriate software. SAMSys decided to develop such a reader, but it knew that to succeed it needed to convince large players of its vision: tag suppliers, package makers and RFID system users.

To influence tag suppliers like Texas Instruments, Philips and Motorola, SAMSys had to position itself as a complementor rather than a competitor. To do that, it took the bold step of exiting the tag business and focusing entirely on making standard-free readers. Even though the large tag suppliers had their own, proprietary line of readers, they saw the SAMSys vision of universal readers as a way of decoupling their tag and reader product lines and significantly growing the tag business. Texas Instruments and Philips are now SAMSys’s alliance partners rather than its competitors.

SAMSys next focused on the package suppliers — the companies that make the packages that house the RFID tags. Over a period of several months, SAMSys persuaded International Paper, one of the largest packaging companies in the world, to enter into a strategic alliance. International Paper now sees SAMSys’s RFID solution as a way to add value to its paper-packaging products. The alliance gives SAMSys access to standards-creating bodies and to research consortia (such as the Auto-ID Center at MIT); more importantly, it gives the company a credible platform for communicating with such potential customers as Procter & Gamble, Revlon and Dell.

Finally, SAMSys, in collaboration with its partners, developed a series of pilot projects to demonstrate the power of its standard-free RFID vision. For example, SAMSys and International Paper are running seven demonstration supply-chain projects — all of which require different readers. SAMSys has created multiproto-col readers that can be configured to fit each project. And a project with Revlon on “smart shelving” caught the eye of Wal-Mart, which is now testing SAMSys’s RFID technology. SAMSys’s vision of a RFID future based on common readers looks increasingly plausible.

Shifting the Traditional Mind-Set

As products from competing companies become increasingly similar, differences in the way rivals interact with their customers are becoming more and more important. There’s no doubt in our minds that strategies built around reducing customers’ interaction costs and risk are central to these differences; they offer a systematic way to tap into new sources of customer value. Make no mistake: It is easy to underestimate the difficulties involved in shifting a company’s focus from products to customer interactions. Tactical marketing responses can’t get the job done because they do the opposite of what is needed, adding to interactions rather than streamlining them. But the tremendous untapped opportunities for creating value and establishing long-term advantage should, we believe, be enough to convince any senior executive of the superiority of a mind-set that starts with customers rather than products.