E-Commerce Is Changing the Face of IT

New information technologies bring new business challenges: threats from new competitors and opportunities to change focus and practices. The business impact of new technology usually receives the most attention —appropriately — but managers shouldn’t overlook the rippling effects on the company’s IT function. IT departments not only must respond to the newly perceived business needs, but, as technologies change, they must adapt their procedures and practices. In the 1990s, for example, companies had to cope with new business drivers (such as business-process reengineering and globalization) while addressing new technologies and techniques (such as client-server computing and IT outsourcing). That forced the IT function to adopt new agendas and practices and to reassess its core purpose and capabilities.1

As companies exploit the Internet, another such transformation is appearing. E-business gurus suggest two key goals for the e-commerce era. The first is a robust and comprehensive IT infrastructure. If the business is online, the technology must be reliable and scalable. The second is the ability to rapidly develop and implement new e-business applications.2 Companies not only must seek early-mover advantages in e-commerce, but also must speed up their capabilities in product innovation and imitation. How can they do that using traditional models of the IT function?

To answer that question, we surveyed 24 companies whose IT departments were engaged solely in e-commerce activities — both dot-coms and incumbent brick-and-mortar companies. We wanted to know how people at the companies perceived e-commerce challenges and whether they were implementing new practices to meet them. We adopted a unit of analysis we called “e-IT,” a term that represents the activities of the IT teams we surveyed.

Our results show that, regardless of company type, the character of the IT function is different in e-commerce, where a variety of new practices and procedures is evolving.

Altered Perceptions

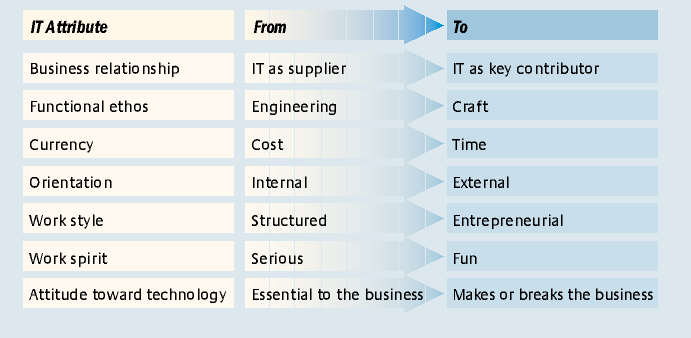

We asked those surveyed — including senior IT and business executives and IT personnel — to describe IT practice vis à vis e-commerce, to highlight any significant differences in the purpose and spirit of the IT function, and to describe the experience of responding to e-commerce demands. We compared respondents’ views to the traditional model of the IT function and identified seven shifts in perception of IT in the e-commerce context. (See “How Companies Believe E-Commerce Is Changing IT.”) Although those shifts may be temporary, new technology clearly has created a disequilibrium — one that is stimulating IT departments to unlearn old practices and adopt new ones.

How Companies Believe E-commerce Is Changing It

”We Are the Business,” Respondents Say

Respondents stated their belief that the IT function had evolved beyond supporting the business to being key to building the business. As the CIO of a spinoff e-commerce venture maintained, “We have gone from supplying services to the business to being the business.”

Many respondents saw distribution channels becoming electronic and business processes becoming dependent on systems. They noted that increasing numbers of products were digital, and information was turning into the source of innovation and future value creation. Because e-commerce could not survive without technology, they believed, IT was no longer merely on the critical path of business development; it had become the critical path.

Indeed, the physical and cultural separations between IT and “the business” seem to be disappearing. Survey respondents revealed that IT and business personnel were located in the same place, worked together regularly and shared responsibility for business growth and survival.

“Our Work Is Becoming a Craft”

Over its roughly 40-year history, IT developed into an engineering profession. Systems development became structured, formalized and automated, with developers relying on generally accepted best practices. The intent was to build industrial-strength systems and robust infrastructures using efficient, disciplined and standardized processes. That approach continues to be valuable for much of IT.

However, e-IT practices are more like the early days of IT. According to respondents, e-IT practices currently are more like craft than engineering. There is much learning by doing and a sense of being free from rules. We heard many remarks about knocking things together to see what happens, changing a design to reflect new ideas and requirements, trying something out and then maybe letting it “go live.”

A craft ethos stems not only from the exploitation of new technologies, but also from the perception that the company has to get new products and channels to market quickly. It also is probably a short-term consequence of the need to mesh technology skill sets. One respondent, for example, mentioned a project that brought together software specialists, program editors, graphics designers, navigation designers and communications engineers.

Indeed, the importance to e-commerce of finding novel ways to do things is one reason incumbent companies created separate e-IT departments in the first place — and why others chose to spin off e-commerce ventures. However, some respondents suggested that the pendulum must swing back a bit if there is to be a true balance between development speed and stable operations. One respondent remarked, “When we look back at early versions of what we built and took to market, we shudder.”

“Time Is the Currency”

An ever growing percentage of corporate capital expenditure is devoted to IT. Annual IT operating budgets continue to grow, and IT costs per unit cost of sale climb. It is not surprising, then, that cost has dominated IT decision making. Companies have long searched for appropriate ways to apply cost-benefit analysis to IT projects.

But in the e-commerce era, at least for the short term, the new currency is time, not cost, according to most respondents. Indeed, the speed of decision-making, applications development, design changes, implementation, technology adoption — all elements of “going to market” — dominated our interview discussions.

Given that IT is the critical path, the respondents saw speed as essential to success. One startup’s chief technology officer commented, “We prefer to be imperfect and be there, rather than be perfect and not be there.” A CIO at an incumbent company reflected, “It’s a time-and-materials business now. You can’t cost things accurately, and time is the driver.” An IT executive in an e-commerce spinoff observed, “Our intended focus was on quality, but we have had to compromise in favor of speed and learning.” Another respondent added, “IT can no longer fall back on excuses like ‘can’t have it that quickly,’ because the biggest sin is not to have something running.”

Business decisions both drive and reflect such perceptions. Some surveyed companies were aggressively pursuing the early-mover advantages of market share — learning and brand building. Most were just concerned with being first to market with new ideas, responsive to customer needs and fast at imitation. One spinoff company adopted “ruthless execution at speed” as its mission for IT — and for all business-development activities. It was determined to achieve goals and market share quickly.

Time permeates business language, e-IT consciousness, e-IT practices and many of the tensions of e-business development.

“It’s About the Customers”

Respondents characterized e-IT orientation as “customer-centric” and “outward-facing.” Traditionally, most IT applications focused on internal elements such as back-office systems and order-fulfillment processing. Even customer-facing systems in sales, service and distribution usually affected a company’s personnel more than its customers. Exceptions such as reservation systems and ATM services were just that — exceptions.

In e-commerce, however, customers, suppliers and partners are all online, and the systems represent the company. Respondents translated that relationship into four IT imperatives:

- be available 24 hours per day, seven days per week;

- have an infrastructure that matches uncertain demand levels;

- understand that applications development is product development; and

- work closely with marketing people.

One respondent captured the essence of the last imperative thus: “The marketing guys are intolerant of long-winded, technical discussions. They are creative and overtly demanding because you’ve got to have a customer spin on everything.”

“We Work Like Entrepreneurs”

The perception about entrepreneurship follows logically from the previous two respondent comments. A loose, entrepreneurial structure hardly fits the traditional disciplined engineering ethos. Discipline means: control regimes created by project management; quality management and service-level agreements; detailed accountabilities; standards, defined procedures and best practices. But if time is the currency and the focus is on markets and customers, the path inevitably leads away from discipline to a more pioneering, entrepreneurial work style. One respondent remarked, “It is fun not to be safe — safe is a boring word.” The e-IT function embraces risk: “Let’s try it: I think I know how.” Companies seem to be reinforcing an entrepreneurial attitude by introducing performance-measurement and reward systems that emphasize revenue growth or time to market.

“The Workplace Is a Fun Place”

The IT world over time came to focus on cost, engineering, discipline and structure. The familiar IT shop is a collection of cubicles punctuated by progress charts, orderliness and a certain lack of soul. The cubicles are occupied for the most part by introverted, serious people with the same skills. Occasionally, someone emerges and talks to someone else.

In the e-IT department, multidisciplinary groups chat over a screen design or gather around a whiteboard. The CEO or COO may be deep in conversation with a programmer. Vision statements may be posted to reinforce business goals. As in a startup, there may be a football table or games area. One spinoff company has a “chill-out zone” where IT personnel can relax. Many companies allow casual dress. As one IT executive observed, “The social and work sides have merged: We enjoy [one another] and socialize while working.”

Thus the e-IT workplace reinforces the entrepreneurial spirit. Our interviews were peppered with words like “fun,” “exciting,” “buzz” and “roller coaster.”

“Technology Is Beyond Essential”

Traditionally, both IT and business executives have been somewhat risk averse when it comes to new technologies and techniques. “Leading edge is bleeding edge” was the mantra. Although they saw that new technologies enabled new business growth, most companies preferred to be quick followers rather than early adopters. Even IT professionals were content to select a “good enough” technology. There was a sound case for appropriate technology — one that matches its sophistication to the business need.3

In e-commerce ventures, the technology-risk profile has changed. Companies are not only willing, they are eager to be early adopters and to experiment. Remarked a CIO in one incumbent company, “We’ve been reluctant to engage in technological R&D in the past, but now it’s becoming an imperative.”

Indeed, during our six-month study, several startups and spinoffs assessed, initiated and implemented new WAP (wireless-application-protocol) cell-phone channels. Others invested in interactive digital television channels as complements to PC-Internet channels. Most of the companies were actively engaged in technology forecasting and scanning, technology R&D and joint ventures with new technology companies. It was not unusual for CEOs of dot-com startups and spinoffs to go on technology study tours and to meet with their counterparts in critical technology-supplier companies.

New Practices

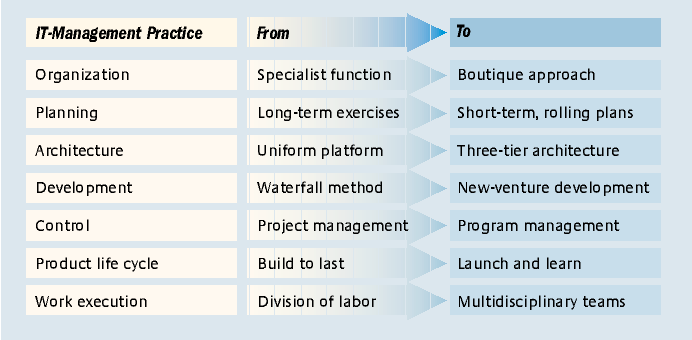

We asked respondents to comment about fundamental IT-management issues. How did they organize and plan, control projects, and develop and maintain systems? What was the infrastructure architecture? The responses identified seven new practices. (See “How Companies See Practices Evolving.”)

How Companies See Practices Evolving

Boutique Organization

Even with outsourcing and downsizing, IT personnel have traditionally numbered in the thousands — up to 10,000 in large companies. Inevitably, the IT function relied on bureaucratic organization: hierarchies, specialist units, support staff, and command and control structures.

E-IT departments, in contrast, are relatively small. A young dot-com startup may have five or six IT people; a spinoff or incumbent business, 20 to 200. More important, e-IT departments behave as if they’re small, preferring flat, team-based work approaches to a hierarchical structure with partitioned specialties.

They also tend to seek the best people and recognize that talent is costly. High salaries, option sharing and bonuses are common. Most companies have adopted (either deliberately or because they had no choice) exacting human-resource policies and procedures. Respondents mentioned induction boot camps; performance-based incentives for meeting time-to-market, revenue-growth or service-level goals; bonuses for recruiting other IT personnel; and employee-satisfaction surveys.

Incumbents as well as consultancies and startups seemed to embrace such approaches in the hope of improving performance and changing old behaviors (one reason that companies created a spinoff or introduced an e-IT department in the first place).

Short-Term, Rolling Plans

Strategy and planning have been top IT-management issues for some time, spawning a variety of methodologies, practices and research — and terms such as “IS-strategy planning,”“IT strategy,”“applications-development portfolio” and “systems long-range planning.”

IS or IT planning was generally for the long term and involved substantial effort. The primary goal was to align IT investments with the business. That involved creating a long-range plan for IT resource development and deployment. IT-application-development projects could last for years, and IT-planning reviews might occur once every three years.

Respondents reported that in e-commerce ventures, IT planning occurs regularly. The CEO and CTO in a young dot-com startup met weekly to agree on prioritizing urgent fixes, missed deadlines, reactive opportunities and next-step business developments. “The vision is constant, but plans change, and details drive tactics,” one person explained.

In one spinoff e-business, the management team reviewed the project portfolio and new application ideas monthly and assessed both priorities and progress. Three months was considered long-term.

In an incumbent company with a separate e-IT department, the e-commerce ventures-management team met with e-IT managers every Monday to review progress and priorities. Said one team member, “We limit our portfolio to six projects, but there are usually 10 requests for new applications, so it’s all about prioritization. … Our IT plan is a project portfolio written on one page showing which projects are in scoping phase and which are active.” Thus there emerged in our research a practice of using short-term, rolling plans — an understandable by-product of dynamic environments.

Three-Tier Architecture

Architecture is the conceptual framework for IT-infrastructure development. Its main purpose is to satisfy the objectives of systems integration, technology inter-operability, platform reliability, application maintainability and IT cost management. In recent years, companies have been on a quest for uniform platforms, aiming for a single desktop or common enterprise-resource-planning system or global data standards.

However, when technologies are rapidly evolving and business change is endemic, architecture design and implementation are difficult, if not impossible. An executive from one dot-com startup told us that, to get started, the IT department begged, borrowed and scraped the bargain basement for technologies. Then the startup found those technologies impossible to scale up, unreliable or too complicated. It is now replacing them as business imperatives and budgets allow.

An e-IT department in an incumbent company we researched patched volatile Web-based, front-end applications onto inherited transaction-processing systems, while simultaneously attempting to ensure reliability and adequate response times. Some application-development boutiques did rapid builds of Web-based customer-facing systems for clients and then contacted their clients’ IT departments to discuss how to connect those front ends to differently constructed back ends. Respondents characterized such practices as “Band-Aids,” “mix and match” and “patchwork quilts.”

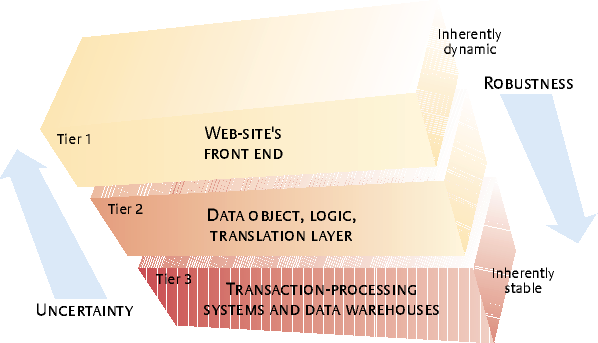

However, a new practice appeared to be overcoming the chaos: the use of three-tier architecture, which dot-com startups and spinoffs were the first to embrace.

Three-tier architecture takes into account both the short life of volatile front-end e-applications and the need for stable, robust, reliable back-end applications. (See “Three-Tier Architecture: Balancing Speed and Stability.”) Front-end applications form the first tier, which is connected to the third, back-end-applications tier by a middleware or technical-wrapping tier. The middle tier translates data messages between the two layers, stores processing logic and data objects (data-handling subroutines), and provides a gateway between ephemeral systems and more-permanent ones.

Three-tier Architecture: Balancing Speed And Stability

New-Venture Development

Students of IT are brought up on the waterfall method of systems development, a sequential approach that begins with a feasibility study and ends with implementation and maintenance. The method is formal and logical; it provides a rigid structure and suggests review points for project planning and control. But in the e-IT world, our respondents contended, it is “too linear,” “doesn’t appeal to creative designers,” “takes too long” and “can’t cope with continuous ideas and change.” The interviewees said some companies find even the more evolutionary and iterative versions of the waterfall method too rigid.4 Hence, they said, they are opting to make systems development more like new-venture development.

Companies are making aggressive use of “time boxing.” Some respondents reported that their organizations would undertake systems-development projects only if they could complete them in three months or less. Many companies wanted to reduce the elapsed time of any stage to one month or less. Even redeveloping an early, fragile system to a more robust version shouldn’t take more than nine months, respondents insisted.

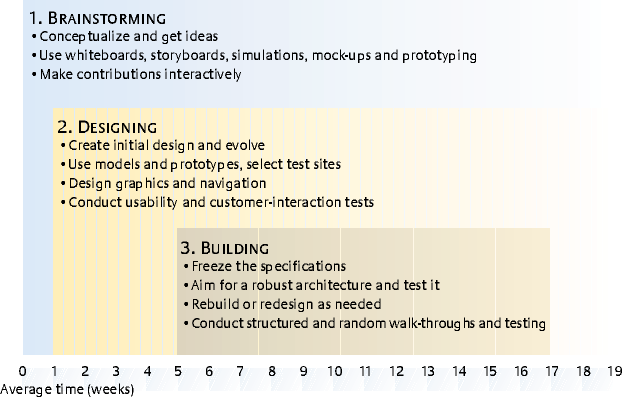

We also found companies compressing the traditional seven steps of the waterfall model into three phases, which we liken to the early financing phases of new business ventures: the concept phase, the design phase and the first-application phase.

Concept phase.

In the concept phase, a team spends one or two days (or a week to a month for larger projects) brainstorming, storyboarding and rapid prototyping. The idea is to develop a business or product idea and visualize it as a simple system. The team typically comprises business strategists, commercial managers, software developers, graphics and site-navigation designers, modelers and storyboarders. Any or all may contribute to conceptual development.

Design phase.

The design phase typically lasts from one week to one month and produces a richer and more robust design. Graphics and navigation designers take center stage here, along with modelers and software developers. Usability and customer-interaction tests are important in the design phase.

First-stage-application phase.

In this stage, which can last from one to three months, technology specialists attempt to make the application robust. They even may throw away the prototype from the design stage and start over.

Although the respondents did not cite a particular methodology for systems development, we inferred the basis of a framework to capture the new-venture approach. (See “The New-Venture Approach to IT Development.”) Our ideal model adds a review point at the end of each stage and renames the stages brainstorming, designing and building.

The New-venture Approach To It Development

Program Management vs. Project Management

In traditional IT departments, project planning and control mechanisms are essential management tools. Using the waterfall method as a template, companies draw up and monitor various time, cost and resource schedules. Procedures for controlling change are commonplace, as are mechanisms that let managers sign off on each stage. Companies typically try to implement best-practice or proprietary project-planning and control systems. Project managers play a key role.

Respondents indicated that in e-IT, time is currency, so time-boxing and time-to-market considerations drive the planning and control of systems development. Typically, site-launch or product-launch dates push the project, and as deadlines approach, companies sacrifice functionality and sometimes robustness in favor of speed. E-commerce projects are business projects, and companies often have to fulfill implicit or explicit promises made to customers. “Delivery means delivery,” said one respondent.

Project management has to be simple. Often there are no project managers at all; startups and young spinoffs, in particular, cannot afford them. Instead, IT and business managers continually review plans, progress and priorities.

However, respondents also identified related activities that needed planning, monitoring and implementing in parallel with IT-applications development. With systems being the product, channel or business process, the IT function had to concern itself with promotion, partnership agreements, legal matters and content acquisition. Hence some of the startups, spinoffs and incumbents in the survey were experimenting with program management — assigning an office or a manager to oversee and coordinate all projects and all aspects of them, including systems development.

Launch and Learn

The engineering ethos of traditional IT both grew out of and cultivated a build-to-last philosophy. As a result, some businesses are still running on core applications that are more than 25 years old. Although “legacy system” has acquired a pejorative connotation, the term also should be viewed as complimentary: Legacy systems have proved reliable and enduring.

By contrast, the systems built for e-commerce are often disposable. Companies build them on a launch-and-learn principle, driven by time-to-market goals. The cost is the minimum feasible, and the main point is to learn about the product, channel or market.

A respondent from one startup described the systems activity as “doing, adapting and then doing again.” Another person from a large incumbent company reported that the company always expects “to throw away the first version.” Although that is not a new idea, it is only just now recognized as good practice.

A respondent from a spinoff said, “We will go to market even if the system is incomplete and linked to the back end with wires and tape.” Another individual, from an experienced spinoff, found the working life of a typical system — perhaps 18 months to two years — so short that “it’s not worth documenting either the system architecture or the coding.” One incumbent company decided to abandon early versions of a Web-based application whenever the business idea is clearly wrong, but it saves the code because of the possibility of reuse and decreased time to market.

The launch-and-learn approach may be a transient policy, appropriate only when business models are evolving fast. It may be a way to adopt the new-venture methodology and then revert to the traditional waterfall development method as requirements stabilize. In any case, it exemplifies what respondents perceived as e-IT’s entrepreneurial approach.

Multidisciplinary Teams

The traditional IT department is built around specialist jobs. A typical hierarchy consists of application programmers, systems programmers, systems analysts and project leaders. Each role is clearly defined, and the demarcation between tasks is relatively unambiguous.

In e-IT, software developers, technology experts, graphics designers, business strategists, usability engineers, navigation designers, marketing specialists, modelers and media designers work collaboratively — especially in the brainstorming and design phases. Although they bring their own expertise, they often contribute ideas outside their specialty. Demarcation lines are porous, and anyone may contribute to the system’s concept and design if the ideas advance the endeavor.

One respondent reported a project in which experienced media and Web-site producers worked with systems designers. The CIO of an incumbent business observed that “even marketing managers are working with techies now.” A CEO of an established dot-com reported seeking IT specialists who are excited about the business and are team players.

Four Guiding Principles

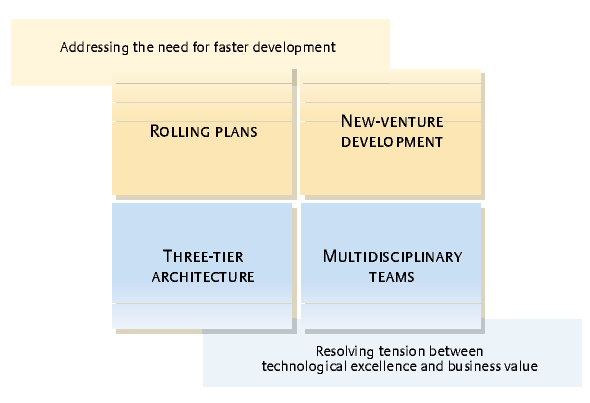

Four principles seem to dominate the new IT function in both e-IT and traditional IT departments. (See “Four Guiding Principles for IT in the E-Commerce Era.”) They suggest new paradigms for four central tasks of IT management: IS planning, systems development or acquisition, architecture design and implementation, and the management of user-specialist relationships. Although none of the companies surveyed was applying the principles as part of a cohesive framework, we believe they can help both e-IT and traditional IT departments cope with the challenges of the e-commerce era.

Four Guiding Principles For It In The E-commerce Era

Two principles — rolling plans and new-venture development — address the need to speed up systems development. The other two — the use of three-tier architecture and multidisciplinary teams — help resolve two classical tensions in IT management.

Rolling Plans

Companies can use rolling plans to become more proactive in adopting new technologies — and more responsive to fast-emerging market needs, problems that arise in the daily operations of e-commerce, and sudden shifts in strategy. Rolling plans also provide a mechanism for IT and business executives to jointly review projects. And they seem to be an effective way to integrate IT and business concerns because they don’t leave planning up to IT executives alone.

The essence of rolling plans is that they are short-term —perhaps no more than three months. They are reviewed at least monthly and enable organizations to change the priorities and scope of any system.

New-Venture Development

New-venture development resolves the tension between formal methodology and the evolutionary approach. It permits an evolution from a loose, conceptual exploration through iterative design to tight implementation, and it provides a framework for financing and rollout decisions.

The essence of the new-venture development approach is that time is the currency; all project contributors are guided by that. It is probably easier to implement in startups and spinoffs than in e-IT departments of incumbent companies. However, it may be the right tool to stimulate the cultural change that incumbent companies require if their IT departments are to meet e-commerce challenges.

Three-Tier Architecture

Business and technology uncertainty has always limited the degree to which IT architectures could be comprehensive and stable.5 Thus companies confronting rapid change may find a three-tier architecture more realistic than other architectures, and some surveyed companies indicated an intent to pursue it.

The key to successfully implementing three-tier architecture is to recognize what should be adaptable and what should be more stable. Clearly, acquiring or developing good middle-ware is critical. Some companies are even experimenting with sophisticated multitier architectures, involving progressively more-stable layers from front end to back end. However, the three-tier architecture is simpler and capitalizes on legacy systems.

Multidisciplinary Teams

IT executives who have worked in both old IT and e-IT seem to value the principle of multidisciplinary teams most of all. To ensure that it continues as their e-commerce ventures grow, they are encouraging their peers in old IT departments to adopt it. Once advocated as a method to cross the user-vs.-specialist divide, the team concept has emerged naturally from the dynamics of e-commerce.

The essence of the multidisciplinary principle is collaboration and co-location. In addition to having sound technical skills, e-IT professionals must like the excitement of business development. Strategists, marketing executives, marketing and creative personnel, and technologists join forces. There is little concern over segregating IT skill sets. The linguistic apartheid of “business” vs. “IT” becomes obsolete for several possible reasons. First, some of the new skills are not yet codified into specialist jobs. Second, the boutique organization deliberately encourages collaboration. And finally, because systems development is business development, interdependence is logical. E-IT begins its life in small startup or incubator situations, where co-location is inevitable. Once managers see the advantages of multidisciplinary teamwork, they are determined to preserve it.

Coping With New Ideas

The folding of many dot-coms did not invalidate our findings. Our survey included incumbent companies and was conducted after the first wave of dot-com collapses. (See “How We Surveyed Companies About IT and E-Commerce.”) Moreover, we have continued to track progress in the companies we studied and have found little change in their initial perceptions.

We urge company executives and managers of IT units whose sole scope is e-commerce to weigh the merits of adopting the seven generic practices and employing the four guiding principles described here. It is time to stand back, reflect on recent changes and stabilize activities.

And those who manage traditional IT departments will find the four principles helpful in responding to the realities of modern business. IT must change the way it views itself. As IT personnel develop Web sites, they contribute to product and customer-service ideas as much as other executives. Systems plans are essentially product-development schedules. Business growth, customer acquisition and time-to-market goals may outweigh technical goals in performance measurement and reward systems. The old IT models break down in the face of such radical changes.

Our survey results only begin to capture and codify the changes. We need hard data on the effectiveness of the new practices and more insight into how companies can implement them. Clearly, businesses are trying to adapt to IT’s evolving character — some more successfully than others. As we learn more about how they have coped, we may finally begin to understand IT’s new face.

References (7)

1. J.F. Rockart, M.J. Earl and J.W. Ross, “Eight Imperatives for the New IT Organization,” Sloan Management Review 38 (fall 1996): 43–55;

J. Cross, M.J. Earl and J.L. Sampler, “Transformation of the IT Function at British Petroleum,” MIS Quarterly 21 (December 1997): 401–423; and

Comment (1)

fcschmitt