Enabling Bold Visions

A CEO’s new vision often blurs into an indistinct image once the initial blitz is over. To ensure that the vision is more than just a daydream, companies should follow a five-phase model that some organizations have used successfully to avoid disaster or complacency.

Topics

It was a beautiful, sunny day in Miami. Inside a darkened auditorium, however, 3,500 senior executives of one of the world’s largest financial companies, flown in for just this purpose, sat awaiting their new CEO. The scene resembled the beginning of a pro basketball game: Loud rock music set the beat, and laser images peppered the crowd and the stage. As the audience members stomped their feet and swayed with the music, the CEO appeared on stage. His task? To pitch his newly minted enterprise vision to the already energized crowd.

His speech, as well choreographed as the buildup, was brief and upbeat. The message was simple: “We will become ‘the breakout firm.’ And to achieve breakout status, we will rely on the three I’s of innovation, integration, and inspiration.” Given the tight schedule of events for this one-day meeting, the CEO took no questions. But the speech had caught the executives’ attention, and the new vision created a buzz of excitement.

Months later, the buzz had worn off. Reality had intruded, as it always does. The company, successful for more than a hundred years, had always proceeded conservatively. Its organizational culture was anything but “break-out.” It wasn’t innovative; its businesses, products and customers were not integrated; and its leaders were not known for being inspirational.

In short, following their initial enthusiasm, the company’s senior executives were having a hard time reconciling the new vision with day-to-day realities as they met in planning sessions with the next levels of management and front-line employees. Within the top executive team, there were few role models for the three I’s, and there were no signs of rewards for behaving as breakout leaders.

Within a year, the term “breakout” had slipped quietly into the background. Few senior executives could even remember the three I’s. About two years after the speech in Miami, the CEO declared victory and went on to lead another company. But the confusion sowed by the unrealized vision cost the company both market share and the harder to quantify elements of trust and momentum with employees and customers.

This gap between inspiration and implementation is a common one. We set out to find out why, and what CEOs and their top teams could do to translate bold visions into operational realities.(See “About the Research.”) In this article, we’ll first explain several common reasons behind the derailment of bold visions. We will then offer a framework that executives can use to ensure that their visions become more than just pipe dreams. Examples of companies that have successfully followed this path will both illustrate the challenges and provide guidance to those who want to actively address them.

Why Many Bold Visions Derail

New visions can fade away for many apparently unique reasons. However, as a result of a search of the literature on organizational change and our discussions with executives from 40 companies, we were able to categorize the reasons for failure into a set of themes.1

Failing to Focus

How many initiatives can any company handle at once? In our experience, an organization can be confronted with a dozen or more major initiatives at a time. If the top team attempts to wrestle with all of them at once, middle managers and front-line employees will likely be confused. The bold vision will get mired in a haze of other priorities, with various initiative champions roaming through the company like prophets crying in the wilderness.

Sitting Out This Dance

It’s awkward dancing without a partner. But that’s essentially what too many leaders of the companies we researched tried to do: They started the dance by explaining the vision but didn’t engage a partner to make it work. They didn’t communicate how others in the company could learn the steps to the new dance. Moreover, employees could walk away from the dance floor without fear, since there was no short-term price to pay for not engaging to make the new vision an operating reality.

Skipping the Skill Building

By its nature, a bold vision can’t simply be retrofitted onto a company. (If it could, it would be a tame or gentle new vision.) But many of the companies we examined did not invest to develop the new skills their people would need to realize the vision. Some leaders didn’t even want to hear that their organizations lacked the capability to execute it. For example, the CEO of the “breakout” financial services company didn’t want to talk about the need to develop collaborative managers and leaders — an obvious prerequisite for the integration plank of his vision.

Mismatching Messages and Metrics

Much is made of people’s tendency to talk the talk without walking the walk — and that general problem applies in this instance, too. Many executives told us that a bold new vision often bumped up against subtle reinforcements of business as usual. For example, it would become clear through the stories floating through the organization that yesterday’s leadership behaviors were still seen to be of paramount importance in spite of the need for changes to fit the vision. Further, we learned that performance management processes and organizational performance measures often remain unchanged, even though newly articulated visions require new behaviors and mindsets.

Clashing Powers

In many cases, an organization’s political dynamics and culture can become a major barrier to the success of the new vision. Powerful groups are often tied to existing core activities that made the company thrive in the past. If the new vision threatens the supremacy of the old guard, political infighting may stall it out and defeat the change agents.

Neglecting the Talent Pipeline

According to the managers in our study, the challenge of bringing about a new vision is, in essence, a change management challenge. What’s needed to make it work? Layers of change agents, from top to bottom — a critical mass of people who embody the behaviors and values of the new call to action. But many companies lack such pipelines of talent, filled with people who are capable of this critical task.

These six problem areas explain why many bold visions fail to produce measurable change, far less ignite their companies to reach new heights. But a model of change can help companies avoid this trap.

The Change Model

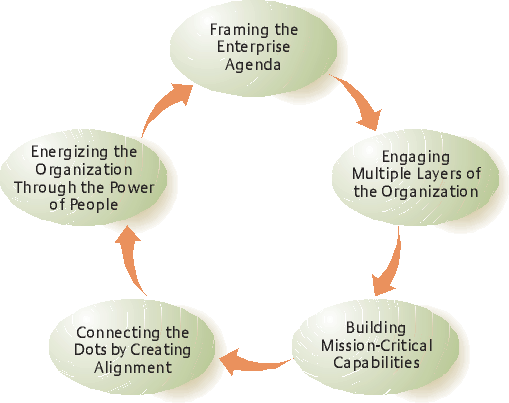

While our research uncovered reasons for the failure of bold visions, it also led us to discern a pattern followed by companies that successfully translated a vision into action. We observed five critical activities, performed in sequence, that together form a systems approach to enabling visions. This approach can be described as a framework for leading large-scale, enterprisewide change initiatives. (See “The Five-Phase Model for Enabling Visions.”)

The Five-phase Model For Enabling Visions

The Five-Phase Model for Enabling Visions

Companies that successfully put new visions of the enterprise into practice follow a process that takes the organization through five phases. In today’s competitive landscape, this is an iterative process: While companies may be able to stick with a single vision for a few years, most will need to return to the process regularly.

Phase I: Framing the Agenda

If an organization’s top executives are spending much of their time attending to competing “top priorities,” they’ll gradually put the CEO’s vision on the back burner, where it will slowly simmer down to nothing. The leaders in our study who successfully brought about change framed their organizations’ challenges as compelling stories that created an urgent agenda for action.

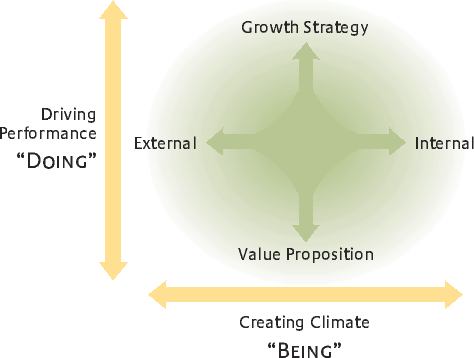

They used the stories to set priorities among the many challenges facing their organizations, with a laser focus on the need to drive performance and to develop the right organizational climate. They often cast the need to drive performance in present and future terms — as a matter of finding pathways to future growth while maintaining the edge that enabled the company to deliver value to customers in the short term. In addressing the need to create an organizational climate that was consistent with the company’s performance objectives, these change leaders took into consideration both external (brand, corporate social responsibility) and internal (culture, values, behaviors) concerns.(See “The Enterprise Agenda.”)

The Enterprise Agenda

The Enterprise Agenda

An enterprise agenda must take into account, on one axis, both present and future performance — both the company’s future growth strategy and its current customer value proposition. This reflects the company’s focus on “doing.” On the other axis, the agenda must reflect an organization’s state of “being” — the way employees and other insiders are affected by the climate of change, as well as the way customers and other external stakeholders perceive the company’s new vision.

Consider the approach to change taken by the British Broadcasting Corp. Like many established media companies, the BBC has been under assault by the proliferation of media options, a problem that has intensified with the advent of inexpensive and easy-to-use digital technology. Customer choice has fragmented, and the network’s market share has steadily eroded. Gone are the days when a popular sitcom could attract more than 28 million viewers, as one did in the 1960s.

The company needed to change to meet these challenges, but it had to navigate risks. It had to chart a course that would not destroy its proud heritage or instigate a flight of the talent that had always been the bedrock of its core competence.

When Mark Thompson was hired as the BBC’s new director general a few years ago, he inherited an organization deeply entrenched in the analog world. Innovators elsewhere in the industry were already moving with dispatch into the digital world. But Thompson didn’t move immediately to bring about big changes. He took some time to make sure he understood the core competencies of the organization and how they matched up against the future direction of the industry. He got to know the cutting-edge elements of the future of the business as well as the best way to frame the BBC’s new vision for success.

After a great deal of listening to industry experts, customers and employees, Thompson framed the BBC’s new enterprise agenda: Creative Future. His message was simple. In order to drive performance, the BBC would invest heavily in digital technology and become leaner and smaller (by becoming better at aligning programming with an improved customer segmentation capability). And in order to create the climate suitable to achieve these performance objectives, the BBC’s leaders and managers would need to become more agile and collaborative. This framing of the agenda was clear: As the competitive landscape shifted, the BBC would not sacrifice quality, but it would make tough decisions about programming and head count.

Another storied company facing the imperative to change recently was Deutsche Bank AG, based in Frankfurt, Germany. In this case, globalization, not technology, was the primary force at work. By the early 1990s, the 150-year-old retail and commercial bank still had its roots firmly planted in Germany. Its top executives and managers were virtually all German, and nearly 70% of its core business was conducted in Germany. But a strategic analysis of the company’s future prospects revealed the likelihood of trouble in the near future: The bank’s growth potential in both retail and commercial banking in Germany amounted to roughly 2% per year.

In contrast, growth prospects in other areas were much more robust: 10% per year in capital markets and investment banking, 5% in asset and wealth management, and unquantifiably huge growth prospects in the Asia Pacific region and throughout the rest of Europe. But to exploit these opportunities, the bank would have to undergo two major transformations — from domestic to global player and from a narrow focus to a broad one, as a fully integrated financial services institution with new core competencies in capital markets and investment banking.

Facing possible extinction if it continued on its present path, Deutsche Bank, led by Josef Ackermann, responded with a bold new vision: the One Bank initiative. Ackermann, chairman of the Deutsche Bank Group’s executive committee, knew that One Bank wouldn’t work if it was just a slogan. “We had to make sure that we were moving from a one-culture bank to a one-bank culture.” And today the bank’s executives are quick to point out that One Bank is only a part of the story of the company’s impressive transformation.

In framing the bank’s enterprise agenda, Ackermann launched the Business Realignment Program in conjunction with the One Bank initiative. This program ensured that the Group’s executives and managers would know precisely what the company’s priorities were and where the Group was heading over the next decade. The program also placed the capital markets and investment banking divisions at the core of the bank’s growth strategy while stressing the importance of integration. Again, driving performance and creating climate — within a construct of ruthless prioritization — were the twin goals.

As Ackermann put it, “We must view ourselves as one bank and one team with one shared goal. We intend to implement the idea of ‘One Bank-One Team’ as swiftly as possible. Utmost priority will be given to removing the silo mentality.”2 To reinforce this dual emphasis, Ackermann approved new leadership standards and cultural values that were directly linked to the One Bank initiative. With these changes, Ackermann made it clear that performance and climate would go hand in hand at Deutsche Bank.

Sometimes companies find themselves in dire situations but still need a leader to spell out, in detail, just how serious the problems are. This bad-news-first approach can be critical to the framing of a bold vision that will get a company moving away from the status quo as quickly as possible. In 1999, when Carlos Ghosn took the helm at Nissan Motor Co. Ltd., he stressed several dismal facts. Nissan had just lost its position as Japan’s second-largest carmaker. Market share had, in fact, been declining for two and a half decades. Fewer than one Nissan model in 10 was profitable. Against this background, Ghosn told the company that the Nissan Revival plan was the company’s “last chance.” Employees got the message.

Phase II: Engaging the Organization

Once change leaders have framed their agendas, they must do whatever they can to distribute “ownership” of that vision as broadly as possible. But this has to be done the right way. We found that while managers and even executives yearn for more leadership in their organizations, they don’t want to be cast simply as followers. Instead, they want a different style of leadership, one characterized by authentic collaboration and broad-based engagement.

This finding gets to the heart of why we emphasize that bold visions must be enabled rather than merely executed. Visions that are truly bold will create tension and anxiety within an organization’s business-as-usual stakeholders. Great change leaders understand this, and they don’t make those who have succeeded under yesterday’s business model enemies of the new vision. They invite differing views and perspectives and listen carefully to those who contribute legitimate arguments concerning the tensions created by the newly framed enterprise agenda.

Carlos Ghosn was particularly keen to solicit new ideas and to get new voices to speak up. At the beginning of his tenure at Nissan, he created nine cross-functional teams and staffed them with middle managers in their 30s and 40s from different functions, divisions and countries. Each team had only 10 members. To keep discussions fluid, a facilitator was assigned to each; to ensure that the teams had authority and were not influenced by a single function, each had two board-level sponsors.

Only three guidelines were set out for the teams’ work. They had one goal: to make proposals to reduce costs and develop the business. They had one rule: no sacred cows, no constraints. And they had one deadline: three months for final recommendations. In the end, the cross-functional teams were a powerful vehicle for returning Nissan to profitability. Critically, Ghosn had not simply issued orders from the top about how to realize the new vision. Instead, he had engaged the company’s managers to find their own routes to success.

Mark Thompson’s strategy to engage the BBC’s stakeholder communities with his Creative Future vision started at the top. The director general engaged the BBC’s board of directors in a series of dialogues that eventually produced a set of recommendations for restructuring the BBC along four criteria: creative, digital, simple and open. The board owned the overarching direction of the restructuring. It left to Thompson the task of engaging his managers and executives so that the restructuring would come to life in day-to-day operations.

Thompson followed through by bringing teams together from different BBC groups — Vision, Journalism, Audio & Music and Future Media and Technology. The task was to work through the details of how the BBC would transform itself from a collection of separate units to a unified organization that relied heavily on cross-unit collaboration. Eventually this engagement process also paved the way for Thompson to restructure the company into three multimedia output groups and to merge the Future Media and Technology team with the new Operations team. Collaboration moved from being an articulated but unrealized value to an ingrained way of working at the BBC.

Similarly, Deutsche Bank’s Ackermann launched a variety of engagement initiatives to enable his vision. For senior-level leaders, he led a series of dialogues called the Spokesman’s Challenge. These were open discussions led by Ackermann and his top executive team that focused on listening to the concerns of his enterprise leadership team. The outcome? A better understanding of the tensions that might get in the way of making the One Bank initiative come to life.

Ackermann also created the One Bank Task Force, a group focused on engaging successive layers of management so that they would also own the vision and become part of the solution. In addition, he skillfully used Deutsche Bank’s Learning and Leadership Development Operation to initiate programs that were directly linked to implementing the One Bank vision.

While Deutsche Bank and the BBC faced compelling reasons to change, their situations were not as dire as that of Mattel Inc. in 2000. In May of that year, Bob Eckert became CEO of an organization that was in deep trouble. The company had fired its previous CEO over the disastrous acquisition of an electronic games company. Morale was low and finger-pointing was high. Eckert set out to engage the organization with a vision of greater collaboration — a vision that would eventually be called One Mattel. In that spirit, a team of line managers approached Eckert and asked if they could craft a set of new values for the company conveying collaboration. The team came back with four values that all built on the word “play” — Play Fair, Play Together, Play with Passion and Play to Grow. Since these values accurately captured the aspirations of many employees, they were quickly and enthusiastically adopted by the organization. Just as important to the success of One Mattel: the engagement of the company’s line managers.

Phase III: Building Mission-Critical Capabilities

While engagement with the new vision is critical, it’s not enough. The development of new capabilities is also necessary, as companies usually have gaps in what they want to do and what they can do.

The process of building mission-critical capabilities is no small challenge, however. We identified two significant problems in the course of our research. First, there are the practical concerns: How do you go about identifying which capabilities will provide differentiated competitive advantage? Second, there are political concerns: How do you identify and address capability gaps without turning the process into an enterprisewide blame game? Either or both of these concerns can become cancerous if matched with a CEO with a short attention span who “just wants to get on with it.” This underscores the importance of following the phases sequentially. After all, it is difficult for a CEO to have a serious conversation about building new capabilities without first framing the enterprise agenda and engaging the organization in an active dialogue.

Without proper leadership, the BBC’s Creative Future initiative could have foundered during this phase. In order to realize the full benefits of Thompson’s bold vision, the BBC required new skills and capabilities and cross-unit collaboration. But the organization was constructed of durable silos with a “craftsman-ship culture” in each silo that guided career development decisions of its managers and employees.

Addressing these challenges was not the work of a moment — or of a single program. Thompson attacked the problems in a variety of ways. He brought the BBC’s technologists together from across the organization to create what he referred to as a “powerhouse resource.” He brought in or developed the expertise required to launch new multiplatform initiatives — that is, initiatives that transcended a single medium or product. He oversaw the introduction of Stepping Stones, a program to create a better understanding of different parts of the Vision Studios and to enable BBC producers to work more flexibly. He launched Hot Shoes, a developmental program that encouraged hundreds of staff to try out their expertise in other disciplines throughout the BBC, allowing them to see what new skills they might need to span boundaries or develop capabilities for new growth areas in the industry. Finally, he initiated the Journalism College Web site, enabling more than 8,500 journalists to sharpen their skills in editorial policy and in emerging fields of the craft. The sum of these programs was a newly skilled base of employees who could work across platforms and had a deep understanding of digital media.

Despite the differences in industry, Deutsche Bank’s capability-building challenges were strikingly similar to those of the BBC. Its organizational structure was also formed by silos, and its future depended upon how well Ackermann could break them down.

But in Deutsche Bank’s case, more than just skill building was needed. The bank also had to cut costs deeply in order to become more operationally efficient. Ackermann shed some of the bank’s portfolio of businesses and acquired and reorganized new businesses that would serve as growth platforms. He targeted markets in other parts of Europe, the Americas and particularly Asia. He made English the official language of Deutsche Bank and carefully moved executives and managers across business and geographic boundaries to build a global mind-set and a collaborative culture. And he used the leadership and learning programs not only as phase II engagement mechanisms but also as critical capability-building tools for his managers.

Phase IV: Connecting the Dots By Creating Alignment

Bold visions rarely succumb to frontal attacks. The companies that collaborated with us in our study mentioned repeatedly that bold visions get derailed by more subtle means: by mind-sets, systems and processes that are out of sync or, ironically, by the unintentional messages sent out by the very executives who are trying to enable the visions to take root.

For example, one of us was engaged by one of Korea’s leading “chaebols” (conglomerates) to facilitate a leadership initiative. The goal was to build a global mind-set among the group’s senior executive team. In the audience were 55 Korean business-unit presidents, all men. The discussion was proceeding well until the topic of reconstructing the top team came up. The suggestion was made to establish a guideline metric that would call for one or two of the group’s presidents to be either female or non-Korean.

The suggestion was greeted with amused disbelief. But that response illuminates a broad problem that afflicts people in any country: Companies and their employees are hard-wired to resist change. We have observed similar roadblocks when companies attempt to align processes — such as those for performance management and rewards — with new visions.

For example, many companies today are trying to break down silos to deliver integrated solutions to their customers. They are trying to enact “one company” visions. And yet they frequently continue to measure and reward their managers solely on their ability to meet unit objectives. Such outdated processes do nothing to encourage cross-unit collaboration in the service of enhanced customer-value propositions.

What can be done to align processes with a new vision? When Josef Ackermann first launched Deutsche Bank’s One Bank initiative, there was a good deal of discussion but little actual business transacted as a result of cross-unit collaboration. That began to change when two of the bank’s executives, Anshu Jain, head of Global Markets, and Pierre de Weck, head of Private Wealth Management, signed a Global Partnership Agreement. The agreement set the stage for a robust collaboration between the two divisions. The two business heads figured out how to work together to satisfy clients’ needs, as well as how to share revenues and profits from those clients.

This wasn’t the only example of parts of the bank learning to collaborate. Other approaches to aligning the company’s systems, processes and mind-sets with the One Bank vision include:

- executive development activities undertaken as a team, with leaders from different divisions taking part;

- the establishment of a unit-by-unit performance measurement process that tracked business generated by boundary spanning;

- changes to the executive succession process that took into consideration the extent to which emerging leaders exhibited cross-boundary behaviors;

- and the institution of the One Bank award, a formal recognition by the Group Executive Committee of exceptional behavior in service of the new vision.

The alignment of vision and process can also be reinforced by changing organizational structure and its support mechanisms. For example, following the restructuring of the BBC’s departments, Mark Thompson created a new Operations Group. The group was set up to bring leadership, direction and consistency to the BBC’s big infrastructure projects, a critical element of the Creative Future vision. Thompson also linked cost-cutting measures in functional departments to the enablement of the vision, since cost savings could be funneled directly into new investments. Thus, members of the finance department could see how their efforts to develop new accounting and finance systems were contributing $100 million toward the Creative Future initiative. By such simple yet creative means are the hearts and minds of large organizations won.

Phase V: Energizing the Organization Through the Power of People

No vision of the enterprise can come to life without the enthusiastic support and follow-through of literally thousands of managers and employees. Individuals in every business, function and region play a critical role in enabling a bold vision to move from inspiration to implementation.

But do companies have the talent they need to see a vision through to completion? The respondents in our study expressed deep concern about this issue. Specifically, they worried that their leaders were placing too little emphasis on identifying and nurturing the talent pools that would be needed. The problem was not a lack of talent management and succession systems — 97% of those participating in the research indicated that their companies had such systems in place. However, an almost equally large percentage indicated that their companies lacked a free and flowing pipeline of talent sufficient to execute their organizations’ competitive strategies. Pressed further, the respondents indicated that most companies’ talent management systems were not in sync with their future capability requirements.

This finding leads us to conclude that leadership failures are not so much a matter of struggling individuals, the focus of most leadership studies. Instead, such failures stem from executive inattention to the connections between talent requirements and competitive capability requirements. All too often, the problem is not that leaders are failing their companies, but rather that a company’s talent policies are failing its leaders.

Great change leaders are deeply committed to, engaged in and accountable for building robust talent processes. They do not delegate this job to the human resources department. The BBC’s Mark Thompson brought in a new head of BBC People, as it is called, with the express purpose and mandate to create a human capital strategy that is directly linked to the corporation’s Creative Future vision. All division heads engaged in and signed off on the strategy and committed to implement it with the same rigor they would apply to their marketing or operations strategies.

Deutsche Bank’s Ackermann demanded that the company’s entire leadership curriculum be re-engineered in accordance with the Business Realignment Program and the One Bank vision. The bank’s programs now are focused directly on global leadership, managing networks and organizational complexity and leading across business and geographic boundaries — all essential ingredients in making the One Bank vision a sustainable success.

Even companies that do not face immediate threats need to consider how to keep their people energized. Starbucks Corp., for example, has yet to face major barriers to its growth. In 2006, however, the company launched the Grow and Stay Small initiative. Its focus has been to determine how Starbucks ensures that its partners (employees) and customers have the same positive experiences that they had when the company was much smaller as well as identify the forces affecting the culture. Through the engagement of partners and customers, the company is identifying the common ground needed to “stay small” culturally while building support for enterprisewide initiatives that build on this common ground.

Continuous Revision

Just a few decades ago, organizations could stay the course with a strategy for a period of years. The idea that a new vision would be needed, perhaps with some frequency, would have been treated with mild amusement, if not outright derision. But competitive realities have forced executives to rethink what their companies are doing, and how they are doing it, over and over again. Auto manufacturers like Nissan see profitability and market share evaporating. Media companies like the BBC face the hostile world of disruptive technology. Financial institutions like Deutsche Bank discover that a one-country focus is a path to extinction. In such conditions, bold visions are called for — and will be called for again, probably sooner than any executive would like.

Let’s stipulate: A bold vision that fundamentally misreads the competitive landscape has no chance of success, regardless of the process used to make it reality. The vision has to be on target, sophisticated, inspiring and far-seeing. Once those difficult criteria have been met, however, a process is needed to take the vision from its birth — as words thundered from a podium by the CEO as rock star, for example — to a new way of doing business. By following the model outlined here, executives can sustain the momentum, and see through the changes, of enabling bold new visions.

References (2)

1. See, for example, J.P. Kotter, “Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail,” Harvard Business Review (March–April 1995): 59–67; L. Bossidy, R. Charan and C. Burck, “Execution: The Discipline of Getting Things Done” (New York: Crown Business, 2002); D.A. Ready, “Leading at the Enterprise Level,” MIT Sloan Management Review 45, no. 3 (spring 2004): 87–91; D.A. Ready, “How Storytelling Builds Next-Generation Leaders,” MIT Sloan Management Review 43, no. 4 (summer 2002): 63–69; J.C. Collins and J.I. Porras, “Building Your Company’s Vision,” Harvard Business Review (September 1996): 65–77; M.A. Roberto and L.C. Levesque, “The Art of Making Change Initiatives Stick,” MIT Sloan Management Review 46, no. 4 (summer 2005): 53–60; C.K. Prahalad and G. Hamel, “The Core Competence of the Corporation,” Harvard Business Review 68, no. 3 (May–June 1990): 79–91; M. Beer and N. Nohria, “Cracking the Code of Change,” Harvard Business Review (May–June 2000): 133–141; D.A. Ready and J. Conger, “Make Your Company a Talent Factory,” Harvard Business Review (June 2007): 68–77; E.G. Chambers, M. Foulon, H. Handfield-Jones, S.M. Hankin and E.G. Michaels III, “The War for Talent,” McKinsey Quarterly 3 (August 1998): 44–57; D.C. Hambrick, “The Top Management Team: Key to Strategic Success,” California Management Review 30, no. 1 (fall 1987): 88–108; and G. Probst and K. Marmenout, “Deutsche Bank: Becoming a Global Leader With European Tradition,” European Case Clearing House no. 306-529-1 (Geneva: University of Geneva, 2007).

2. Probst, “Deutsche Bank.”