How Boards Can Be Better — a Manifesto

The nominally independent board of directors is in fact often dependent on management for information. But new pressures on companies, more cooperative approaches and new technologies can render directors increasingly effective as evaluators and advisers.

In the Wake of recent high-profile reversals in the financial services industry, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the limited extent and compromised value of information sharing between companies’ management and boards of directors. Nominally independent directors — those said to be entrusted with protecting shareholder interests — are often dependent on management for information on the very things they are expected to examine, assess and oversee, including management’s performance.

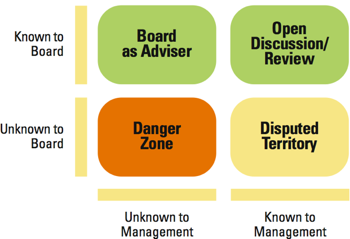

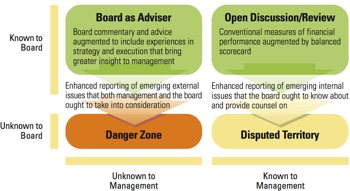

Boards have long been urged, by regulators and activist shareholders alike, to take more initiative in assessing their companies’ performance. But they are unlikely to do so unless they have access to relevant information when they need it. As one recent study on corporate governance emphasized, “the board’s ability to provide meaningful oversight and useful advice is determined by the quality, timeliness and credibility of the information it has. And it’s clear to us that most boards have a long way to go in this area.”1 We refer to the difference between the information available to management and what is presented to the board as “information asymmetry.” (See “Agency Theory and Information Asymmetry.”)

In this article, which draws on interviews with directors and other key players (see “About the Research”), we come to three broad conclusions: (1) the pressures on management and boards to address information asymmetry are likely to increase, (2) high-quality information is as vital to effective governance as it is to superior enterprise performance and (3) technological solutions will dramatically improve the ability of boards to identify, acquire, analyze and act on the most relevant information.

The Pressure Builds

In November 2007, a Wall Street Journal Op-Ed piece written by a former bank executive explicitly assigned to boards of directors a significant share of the blame for troubles in the banking industry, particularly those related to subprime mortgages. “The handwriting has been on the wall for some time,” he said, “and bank boards have made little effort to read it.”2

The mortgage crisis highlighted complex questions for corporate governance in general: What are the minimum amounts and kinds of information that directors need to make prudent business judgments and effective decisions, above all when unexpected events occur? If a surprising decline in financial performance is reported, for example, or a potentially material ethical lapse is revealed, directors may not be able to rely solely on information from management. They may feel compelled by duty and law to seek sources of information that are free from management’s interpretations, analyses and biases — especially if they would later want to demonstrate that they had acted in an informed and independent manner.

Making sure that boards have such information may mitigate crises once they begin, but addressing the boards’ more routine information needs could help prevent crises from occurring in the first place. For example, might bank boards have intervened earlier if they had an accurate picture of their banks’ risk exposures? Rather than treating the board primarily as a monitor that should be exposed to only the most relevant and “processed” information, management may instead want to see the board as a necessary counterweight. Surveys consistently show, in fact, that directors are keen to serve this role and to engage management in discussions of strategic risk.3

Managers and directors should also be aware that the regulatory and legal regime governing information in the boardroom is changing. The current laws in the United States describing the role that information should play in the boardroom to ensure good governance are particularly liable to evolve, as they are confused, conflicted and unclear.

At the heart of the issue is the “business judgment” rule, a legal concept that protects directors should they make a bad business decision. The rule states that a court of law will not decide on the wisdom of a board’s business decision so long as “the directors of a corporation acted on an informed basis, in good faith and in the honest belief that the action taken was in the best interests of the company.”4 However, Yale University’s Ira Millstein, a leading governance scholar and lawyer, observes that the business judgment rule provides little guidance to board members: “Directors are supposed to act on an ‘informed basis’ — but after that, you’re in never-never land.”

Thus, we believe that managers and directors alike should be prepared for the emergence of stricter standards for boardroom information practices. In addition to potential modifications made by Congress and the courts, several plausible scenarios show changes that may result from the efforts of activist investors, sophisticated shareholders, private equity companies, regulators and management itself:

Activist investors clamor to know. Activist and institutional investors, frustrated by unpleasant surprises, demand greater transparency from the board. Through collaboration during investor

forums (where the board meets with key shareholders) or perhaps as a result of a successful proxy battle, boards may agree to work with both

management and investors to come up with

“investor-important” performance indicators for public disclosure. In essence, boards will be forced to reveal the information they deem important enough to influence their decisions.

Sophisticated shareholders insist on sophisticated boardroom information. In this scenario, board members accept that they need better information and more advanced analytics in order to show that they are acting on an informed basis. (See “Information Asymmetry: What the Surveys Say,”) The scenario is influenced by hedge funds’ and institutional investors’ demonstrated ability to garner a thorough understanding of a company’s performance and risks by using publicly available data and innovative techniques. The vice chairman of a large financial services company explained in a recent interview that these developments will make it harder for board members to use lack of knowledge as an excuse for inaction: “You would expect the board members to have known as much as the investors, because the information is available to people who are willing to dig.”

Information Asymmetry: What the Surveys Say

Recent surveys of corporate boards reveal that directors are often largely dependent on management for the information they receive:

- In one study, more than two-thirds of directors lacked access to independent information channels.ii

- In another study, independent directors were found to be less satisfied with the financial, operational and strategic information they received than their nonindependent counterparts.iii

- In a third study, only 10% of directors could obtain company information through an online board portal.iv

Private equity companies claim they know “best practice.” Private equity partners, in an effort to assert their claim to an investor premium, argue that their companies enjoy success not only because of improved strategic positioning and increased operational efficiencies but also because of superior governance. Private equity ownership, they maintain, improves governance, whereas public companies’ weak governance and oversight undermine the value of the company. According to this scenario, private equity’s success creates a competitive benchmarking opportunity for publicly traded companies, which import private equity governance best practices.

Regulatory change broadens the board’s information role. Regulators turn Securities and Exchange Commission chairman Christopher Cox’s vision of real-time reporting and interpretation of business results into reality, as new digital disclosures allow technology-savvy analysts to decide which performance metrics are the most important to follow for any given company.5 The board’s time in this scenario is increasingly devoted to assessing how such investor-important performance indicators should be used to guide or inform management action. In such an environment, the board becomes a more dominant and populist institution.

Management takes the lead. Just as former CEO Jack Welch asserted that General Electric Co. must be No. 1 or No. 2 in an industry or exit it, a Fortune 25 global company publicly declares that its board must be as remarkable as its management. In other words, superior governance is deemed as essential to sustainable success as superior operations. In this scenario, the board devises performance parameters to measure its own effectiveness, which it then synthesizes and presents to investors. This disclosure is soon accepted as standard practice, and boardroom processes become increasingly transparent.

Such changes may ultimately foster stricter standards, but to date most companies have been slow to adapt, for several reasons.

First, directors, managers and corporate counsel may be cautious when it comes to altering the dynamics of the manager-director relationship. Enhanced information in the boardroom might encourage directors to challenge management’s assumptions and projections aggressively, thereby undermining a spirit of trust and openness. With board members reacting more like managers than overseers, the relationship could even become adversarial and counterproductive.6

Second, exposure to more information may pose difficulties for the board, as we discovered in a recent focus group. Adding required information — whether in the form of financial figures, third-party analyst reports or peer comparisons — might overburden directors. The focus group, composed of independent directors, further noted that directors do not always feel they have the specialized skills and knowledge for interpreting information derived from, say, computerized tools for testing different strategic scenarios or financial maneuvers.

Finally, boardroom behavior is often shaped by cultural norms that are slow to change, barring new regulatory guidelines on information or internal crises that may serve as an immediate prompt for change. In our conversations with directors, we repeatedly heard how the culture of a board determines its propensity to pose additional questions to management. One board member noted that it is typically the new directors, especially those who were recently in management, who are more likely to request additional details — often to the consternation of more experienced directors.

Facilitating a Trustful Conversation

We believe that these obstacles can be overcome, especially when directors and managers work together to improve the quality of the board’s assessment of company performance, which relies heavily on access to the right type of information, which in turn is essentially a compromise between two extremes.

At one extreme, if information were selectively and self-servingly chosen by management for presentation to the board, directors clearly could not accurately assess the company’s performance. At the other extreme, however, if the board were overwhelmed with comprehensive yet raw data with little explanation, then effectively assessing the company’s performance would be extremely difficult.

How can a company’s managers and directors avoid each of these traps? The core of a healthy information relationship between them is their agreement on the most useful performance metrics to track and assess. (See “What Are the Right Metrics?”) When such agreement occurs, the benefits to board-level performance assessment are threefold: (1) a rigorous discussion about the proper business metrics can serve to build trust between management and the board, (2) basing directors’ performance assessments on key performance metrics eases the burden on the board to decode reams of data and at the same time frees it from dependence on management’s evaluations and (3) knowing that management has a clear view of which performance metrics are most important to strategy or operations allows board members to focus their time and energies better on the critical performance issues.

What Are the Right Metrics?

Performance metrics should be a set of forward-looking indicators (strategic and operational, financial and nonfinancial) that best measure progress toward a company’s goals. While any company would want to track revenue, operating income and profits, other metrics that management and directors might find useful could vary substantially between industries:

- Operational metrics for a retail chain might include close rates per

number of customers who come into the stores, in-stock levels and speed-of-delivery rates. - An energy company may focus its metrics on throughput diagnostics of

its supply portfolio in order to optimize utilization of wells or mines. - Critical metrics in high-tech manufacturing might focus on manufacturing defects, given the substantial costs involved in making the products.

Ideally, the metrics communicated to the board should match those that management itself uses to assess company performance. According to John Mahoney, CFO and vice chairman of office-products retailer Staples Inc., “We use the same key performance indicators in our monthly board update that we use in our operating reviews with business units.” He believes that there are clear benefits to this practice: “If the board understands we are trying to help them understand the business, and [directors] effectively rely on our information, it facilitates a trustful conversation.”

Trust gives directors confidence that the information they have been given reflects the most critical and up-to-date performance metrics, and it allows them to weigh in constructively on issues of enterprise strategy and risk. For its part, management can feel comfortable drawing on directors’ collective insights, experience and judgment.

Mahoney acknowledges that the practice of sharing management’s key performance indicators with the board is relatively unusual. But as the debate about information asymmetry climbs higher on the corporate governance agenda, more and more managers will be obliged to consider such solutions. Communicating key performance metrics to boards is a way of granting them access to the right information.

The Right Tools For the Job

Once access to such information is granted, new technologies can help directors obtain and use it.

It is inevitable that boardroom information will go online (as long as security issues are addressed) and that the use of interactive, mobile and social networking technologies will rise. As a new generation of executives joins boards, they will bring these tools with them. For example, scorecard or dashboard applications that are currently available — such as visualization tools and alerts — can be valuable to directors. (See “Visualizing a Directors’ Dashboard,”)

Visualization may take many forms, including trend graphs or “heat maps,” which, respectively, indicate performance over time or convey where concentrations of high and low performance occur. These tools give boards the ability to see the business, based on key performance indicators, at a glance. Putting such information at directors’ fingertips, in a format that helps them easily understand its implications, can prompt beneficial board discussions of strategy, risk and the best performance metrics for determining business success.

Alerts at the board level can also be helpful. Just as stock-trading alerts are standard features that let investors know when prices dip below or rise above a certain threshold, alerts are increasingly being used in business operations to reveal critical circumstances.

The information revolution will have other impacts on the boardroom as well. In our recent focus group with directors, most board members expressed a desire to engage in electronic “what-if” analyses using company data. This capability would allow a board to experiment with underlying assumptions that may otherwise be taken for granted, as well as to understand the trade-offs that may inherently exist when success in one performance metric means that another metric cannot be met. It would be useful to know, for example, if the recent banking crisis could have been mitigated had boards run what-if analyses with credit-crunch scenarios.

Another benefit of technology will be the growing ease with which directors may rapidly access outside information and incorporate it into their assessments and decision making. Company data in new digital formats, for example, may increasingly allow directors to retrieve and compare their competitors’ financial disclosures without the need for extensive manipulation. These electronic databases might ultimately incorporate performance metrics that are standardized for a specific industry, meaning that company perspectives beyond financial performance — related to customers, talent or operations, for example — could be compared with those of other companies. The ability to bring independent information to bear on boardroom decision making thus will increase the utility of boards not only as effective overseers but also as advisers on external factors such as competitor strategies.

Toward a Better Board

The rosters of today’s corporate boards reflect pressures from legislators, regulators, investors and listed exchanges to enshrine independence as a major principle of effective governance. Tomorrow’s corporate boards, by contrast, will be expected not only to be independent in terms of their composition but also to act independently. Information asymmetry between management and the board is one of the major stumbling blocks along the path to this future: As long as directors rely on management for information and analyses, they can neither make decisions independently nor effectively monitor company performance. For this reason, the definition of “independence” for boards will increasingly embrace their own information and analyses.

Addressing information asymmetry and enhancing performance assessment at the board level go hand in hand. Tomorrow’s corporate boards should more actively add value to the companies they oversee. Not only might directors engage management in dialogues about the most helpful performance metrics to track, they could also use those metrics to interact with management on broader issues of strategy and risk. Far from being backseat drivers, however, directors could be advisers — capable of complementing management, as in anticipating its blind spots, and offering advice based on their own professional experiences. Moreover, technological tools that support informational needs will play an increasingly prominent role in decision making, both inside and outside the boardroom.

References

1.R. Hardin and J.A. Roland, “Board Work Processes,”