The Need for Third-Party Coordination in Supply Chain Governance

As companies rely increasingly on external suppliers, there is an emerging and compelling need for “maestros”

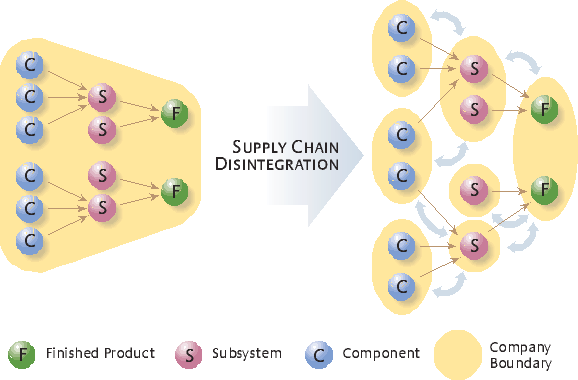

The last few decades have brought dramatic shifts in the manner in which business is conducted around the world. Companies have moved away from hierarchical, integrated supply chains in favor of fragmented networks of strategic partnerships with external entities. (See “The Disintegration of the Supply Network.”) This transformation has caused ripples throughout the old supply network. Many businesses are struggling to compete in the new landscape. However, it is not clear how sustainable the fragmented supply chain will be — particularly for small and mid-size enterprises. Following the period of disintegration, it will be only a matter of time before there is a compelling need for reintegration, which for many companies will have to be coordinated and facilitated by independent third parties.

The Disintegration Of The Supply Network

As economies around the world become more integrated and geographical boundaries fall, it is not surprising that we are witnessing massive changes in the way business is conducted. Many of the starkest changes are visible in the fragmentation of supply chains. In the automotive industry, for example, both Ford Motor Co. and General Motors Corp. have divested some of the most cost- and labor-intensive parts of their manufacturing processes as semi-independent or wholly independent units. A fundamental reorganization is underway throughout the automotive supply chain, as companies everywhere radically revamp their approaches to system management with lean manufacturing and just-in-time inventory.

The same pattern is being repeated in many other industries, and it is particularly dramatic in apparel and textiles, and in electronics manufacturing and service. In recent years, global competition has shifted most of the apparel manufacturing away from developed countries to developing countries.1 In the past two decades, Asia has come to dominate textile and apparel exports, at the expense of producers in Europe. The United States, meanwhile, has become an increasingly major consumer of imported textiles and apparel; its role in this sector has largely evolved to that of designer, developer and marketer.

References (15)

1. G. Gereffi and O. Memedovic,“The Global Apparel Value Chain: What Prospects for Upgrading by Developing Countries” (Vienna: United Nations Industrial Development Corporation, 2003).

2. Veloso, F. and R. Kumar, “The Automotive Supply Chain: Global Trends and Asian Perspectives” (Manila: Asian Development Bank, 2002); and E. Barnes, J. Dai, S. Deng, D. Down, M. Goh, H.C. Lau and M. Sharafali, “Electronics Manufacturing Service Industry,” The Logistics Institute-Asia Pacific, Georgia Tech and the National University of Singapore, 2000.