Integrating the Enterprise

One of the most fundamental and enduring tensions in all but very small companies is between subunit autonomy and empowerment on the one hand and overall organizational integration and cohesion on the other.1 The tensions grow with increasing organizational complexity and assume the most intensity in large, diversified global companies.2 In our research with such organizations, we have seen that it is possible to balance those tensions successfully by implementing four kinds of horizontal integration for achieving cohesion without hierarchy.

Over the last decade, many large companies around the world focused on creating relatively autonomous subunits and empowered managers by breaking up their organizational behemoths into small, entrepreneurial units. Some, though not all, achieved significant benefits from such restructuring.3 Freed from bureaucratic central controls, the empowered units improved both the speed and the quality of responsiveness to market demands — and fostered increased innovation. Companies were able to reduce their corporate-level overhead and make internal-governance processes more disciplined and transparent.

However, the empowerment of subunits also led to fragmentation and to deficiencies in internal integration. The autonomous managers of subunits saw few incentives to share knowledge or other resources, particularly when evaluation of their performance focused primarily on how their own unit was doing, rather than on how the unit contributed to the company’s overall performance.

But today, in company after company, we are finding that management attention has moved to the integration and cohesion side of the tension. (See “About the Research.”) Having captured benefits from strengthening the competitiveness of each unit, companies are now improving integration in order to achieve the benefits of better sharing and coordination across those units.4

Although many companies are moving toward integration, our research shows that the drivers forcing that change often differ. For some enterprises, the main impetus comes from the demands of customers whose needs cut across the company’s internal boundaries. At global engineering company ABB, the 1,300 small companies that Percy Barnevik created in the late 1980s have been consolidated by current CEO Jörgen Centerman into 400, primarily for serving global customers more effectively. Customer needs created similar pressures at OgilvyOne, the world’s largest direct-marketing agency. That company had to roll out the American Express Blue credit card worldwide across multiple media in six months — a task that would have been impossible in the formerly fragmented and internally competitive OgilvyOne.

For other companies, the effects of technological change on management of innovation are the primary integration drivers. For example, with home entertainment shifting from stand-alone, analog-technology-based consumer electronics to Web-based, digitized content delivery, Sony saw the need to integrate its historically autonomous product divisions. Sony had to make all its audio and video products (plus its music and movie software) compatible and accessible directly through a personal computer, video-game machine, PDA or mobile phone. Driven by that fundamental technological change, Sony entered the personal-computer business, the established gateway to the Internet, and launched VAIO computers. The company proceeded to develop an integrated innovation process so that its VAIOs could work seamlessly with all other Sony offerings.

At Oracle, Goldman Sachs and luxury-goods business LVMH, rapid growth and globalization are what’s driving consolidation and integration. Oracle grew at a phenomenal pace internationally, with little time to develop its organizational systems and processes. Each of its overseas units developed its own system to meet the needs of local customers. Over the last two years, the company has worked hard to standardize and integrate those systems and to achieve efficiency and better global coordination.

At BP, the integration driver is different still. BP’s mergers with Amoco, Arco and Castrol created a fragmented organization with many different management styles and philosophies. So integration has been vital for turning the focus of the 100,000 employees away from their differences and toward their shared future. Confronting the same needs are Indian pharmaceuticals company Nicholas Piramal, which grew rapidly through acquisitions, and OgilvyOne, which keeps acquiring Internet marketing companies that differ from its traditional direct-marketing businesses.

A Need for Horizontal Integration

At one level, nothing is new here. The need for integration to counterbalance internal differentiation is an old chestnut.5 But today’s circumstances create some new possibilities and eliminate some historical ones.

The most important change is the Web and the associated information-technology capabilities. Information sharing has always been at the heart of integration, but now technology allows organizations to respond to integration needs in ways that were unavailable even five years ago.6

Meanwhile, some previous integration tools have become less significant: staff relocation and structured career paths, for example. Formerly, in companies as diverse as Unilever, Matsushita and Hewlett-Packard, managers who had worked in different functions, businesses and geographic locations turned their collective personal networks into the glue that held the company together.7 Although such networks are still a powerful tool for socializing people and building organizational cohesion, they are less common — in part because lifetime careers and on-demand mobility of employees can no longer be assumed.

Then, the drastic pruning of middle management that many companies undertook in the 1990s deprived them of an important but often unrecognized source of organizational integration. The midlevel managers who once played boundary-spanning and coordinating roles are gone.8

But perhaps the most important change is in management philosophy. In the past, integration was managed primarily through vertical processes. The way to encourage different businesses, functions or geographical units to share resources and coordinate their activities was to bring them under a common boss and a common planning and control system.9 Although there has always been a recognition of the relevance of horizontal-integration mechanisms, in practice they have been seen as secondary, as reinforcement to the primary vertical processes.10

The most fundamental change we have observed in the ways companies are responding to integration is a move away from the traditional vertical mechanisms of hierarchy and formal systems to a primary reliance on horizontal processes that build integration on top of subunit autonomy and empowerment. The secondary has now become primary.

Four Critical Components of Horizontal Integration

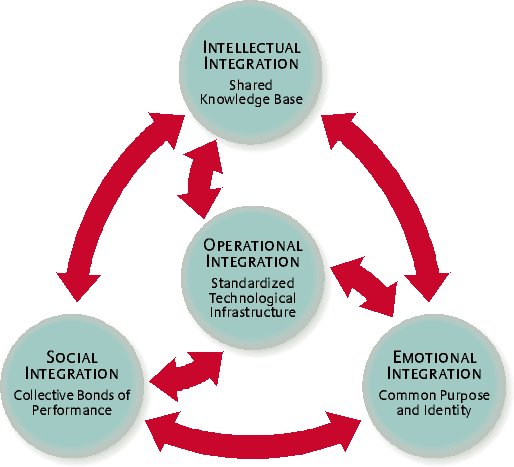

How are companies putting it all together again without destroying the vitality of the parts? We have found four areas of action: operational integration through standardization of the technological infrastructure, intellectual integration through the development of a shared knowledge base, social integration through collective bonds for performance and emotional integration through the creation of a common identity and purpose. (See “A Framework for Organizational Integration.”) The four areas are simultaneously distinct and interrelated. The challenge is to manage the interrelationships synergistically.11

Operational Integration Through Standardized Technological Infrastructure

Influenced in part by reengineering, many companies in the 1990s made progress rationalizing their production and distribution infrastructures. Now the focus of operational integration has shifted to support functions such as finance, human resources, planning and service. The bottleneck in rationalizing and integrating those activities lies in IT systems.

Although many companies have recognized that constraint and are making progress in updating their fragmented IT infrastructure, standardization of support functions is still a distant ideal.

Oracle — whose rapid international expansion resulted in autonomous national subsidiaries using different systems to manage operations — is illustrative. Even as late as 1997, Oracle had 97 e-mail servers running seven incompatible programs. Each country had its own enterprise-resource-planning (ERP) system and its own Web site in the local language. Some even changed the color of the Oracle logo because of the local manager’s taste.

Despite having the same products worldwide, the Oracle organization packaged, bundled and priced them differently in each market. And to find out how many people Oracle employed worldwide on any given day, someone had to scout through 60 differently formatted databases and consolidate the number. By then, the answer would have changed.

Then, in 1999, CEO Larry Ellison articulated Oracle’s direction for the next phase of information technology. He envisioned the computer industry becoming a utility like electricity or water. The hardware, data and applications would reside in a central location and would be accessible over the Internet to any customer with a PC and a Web browser. Oracle would provide integrated services, including ERP, customer-relationship management, supply-chain management and human-resource management. As Ellison explained,“If you want to buy a car, would you get an engine from BMW, a chassis from Jaguar, windshield wipers from Ford? No, of course not. Right now with the software out there, you need a glue gun — or hire all these consultants to put it together. They call it best-of-breed. I call it a mess.”

To convince customers of the value of building an operating infrastructure through standardized and integrated applications over the Internet, Ellison made Oracle its own beta-test site. His metaphor was, “Eat your own dog food,” and he publicly announced a target of $1 billion in cost savings — 10% of revenues.

By 2001 Oracle had met that goal. All e-mail is now consolidated into one standardized, global system using two servers at Oracle’s California headquarters. Prices and discounts, once a local preserve, have been standardized globally and made accessible over the Internet. ERP customizations that differed in every country in Europe are standardized and are operated from a single central source. The different local Web sites have been replaced by a single global site, Oracle.com, which is run out of the United States in multiple languages.

Observers may quibble over how much money Oracle has saved, but most estimates are close to that $1 billion target. Over the two years it took to implement the global platforms, Oracle’s operating margin improved from 14% to 35%. Ellison has now upped the ante from $1 billion in savings to $2 billion, and the company is going through the next round of rationalizing its operating infrastructure to meet the new goal. Having consolidated the technological infrastructure supporting internal operations, the company is now using the same philosophy in its relationships with suppliers and customers — and in its sales and marketing activities.

What have such drastic standardization and centralization done to front-line entrepreneurship? According to CFO Jeff Henley, they have enhanced the kinds of entrepreneurial activity that Oracle values most. “It would be goofy to let people do as they please in building and managing a local IT operation to support internal processes,” says Henley. “By standardizing those, we have channelled that entrepreneurship where it adds value — in serving customers. We think it is a good idea if a salesperson spends time selling product benefits rather than negotiating prices and discounts.”

Oracle has been successful in standardizing its technological infrastructure while most companies have made only incremental progress. What makes Oracle different? The most important factor has been the commitment of a powerful CEO who made the initiative his top priority. To overcome objections from country managers and to accommodate their needs and contributions, he had them participate in designing the standardized systems. Then he gave them a choice: They could either adopt the standardized and centrally operated systems completely free of cost or continue with their local systems (accepting full costs and no adjustment in the returns they were expected to generate). Without exception, the local managers chose the first option.

Standardizing operating processes has always been a powerful integrating device, but it wasn’t possible to create centrally managed, standard IT systems until now. The biggest benefits flow at the extreme, not with half-measures. It may be that the business Oracle is in allows it to do more standardizing than, say, a Unilever, but most companies could still wring more advantage from technological infrastructure than they have so far.

Intellectual Integration Through Shared Knowledge Base

With the goal of “knowledge management,” many companies have developed IT-based systems that are essentially databases for sharing information on an organizationwide basis. Such systems, however, are only the first step in establishing a shared knowledge base that truly integrates a company’s intellectual capital. Because user pull must supplement the technological push, effective integration of knowledge requires a clear strategic link and extensive communication.12

At Ogilvy and Mather’s OgilvyOne, an increased need for integration became apparent in the early 1990s because of two large clients — American Express and IBM. Both demanded integrated services and business solutions that combined interactive media with traditional direct marketing. In the 1980s, advertising agencies used costly mass-media campaigns to attract customers, but in the 1990s, they targeted the “anarchic” customer, who had a choice of infinite channels. OgilvyOne’s historically fragmented organization, with highly autonomous divisions such as Data Consult, Direct Mail and Ogilvy Interactive, simply could not respond effectively.

OgilvyOne decided to focus on customer ownership and 360-degree brand stewardship, building both strategies on proprietary tools designed to support trust and long-term relationships with clients and clients’ end customers.

Customer-ownership tools such as QuickScan (a sophisticated, proprietary data-mining tool) enabled Ogilvy’s creative professionals to question clients’ assumptions about end customers. QuickScan revealed, for example, that only 16% of Nestlé Pet Foods’ customers accounted for 90% of the customer value for Friskies, a major cat-food brand. So OgilvyOne helped Nestlé target the more valuable segment. In addition, the firm employed a complex mathematical model for understanding, developing and enhancing the relationship between a customer and a brand in order to preserve and reinforce every aspect of brand strength.

But to get the most from its tools, OgilvyOne first needed mechanisms for creating, sharing and exchanging knowledge across the company. It had to harness the brainpower of its marketing gurus, mathematicians, statisticians, strategy consultants and individual creative talent. So OgilvyOne developed an integrated system called Truffles. Truffles provided not only a database and a system for testing ideas and hypotheses, but also opportunities for people to generate new ideas together through a variety of chat rooms, bulletin boards and dedicated forums.

The Truffles name came from a statement of founder David Ogilvy: “I prefer the discipline of knowledge to the anarchy of ignorance, and we pursue knowledge the way a pig pursues truffles.” Supported by 60 knowledge officers across the company, the Truffles initiative was the product of years of documenting the accumulated intellectual capital of the company. It was also a living forum for creating and sharing new ideas.

What made Truffles work was not only the world-class IT infrastructure nor the tremendous effort and investment that kept its information current, but also the link between the system and the company’s strategy. With all tools, techniques and relevant data on Truffles, research and ideas were directly connected to action. That link overcame initial resistance and motivated both senior managers and the creative staff to use Truffles.

Also contributing to the system’s success were company efforts to build interpersonal relationships, or “soft bonds,” to promote knowledge sharing. OgilvyOne created many conversation forums — Friday morning breakfast meetings, top-level “Board Away” days and other functions. With the motto that “the most important role of managers is to create friendships,” the senior leaders invested considerable personal time to develop the internal trust that sustains intellectual integration. Nigel Howlett, the chairman of OgilvyOne’s London office, for example, spent months building a relationship with Tim Carrigan, the CEO of NoHo Digital, an interactive marketing company Howlett wanted to buy. The discussions were as much personal as they were strategic. The results of the friendship they built were manifest immediately after the acquisition was finalized. Within two weeks, NoHo’s employees were not only using Truffles, but also were contributing new information and techniques to the database for use by all Ogilvy employees.

Social Integration Through Collective Bonds of Performance

Although learning and sharing are usually achieved horizontally in peer-to-peer forums, performance management and resource allocation are still the preserve of boss-to-subordinate relationships. Our research revealed, however, that enormous advantages can result when peer-to-peer interactions are extended to traditionally vertical areas. As BP’s CEO John Browne recounts, “One theme we observed was the very different interaction between people of equal standing, if you will, when they reviewed each other’s work than there was when a superior reviewed the work of a subordinate. We concluded that the way to get the best answers would be to get peers to challenge and support each other rather than to have a hierarchical challenge process.”

Peer assist, a BP process that uses peer groups of managers from similar businesses to drive learning and knowledge sharing, is already well documented.13 But over the last two years, BP’s new peer challenge has extended that approach to address the traditionally vertical performance-management and resource-allocation processes.

The managers of each autonomous business unit enter into an annual performance contract with top management and are then free to achieve the results however they wish. Peer challenge requires managers to get their plans, including investment plans, approved by their peers before finalizing the performance contract with top management. “The peers must be satisfied that you are carrying your fair share of the heavy water buckets,” says deputy chief executive Rodney Chase. “The old issue of sandbagging management is gone. The challenge now comes from peers, not from management.”14

According to BP business-unit head Polly Flinn, “The peer challenge is about convincing people in similar positions to support your investment proposal knowing that they could invest the same capital elsewhere, and going eyeball to eyeball with them, and then having to reaffirm whether you have made it or not over the coming months or quarters.” The process works because half of the unit manager’s bonus depends on the performance of the unit, and the other half depends on the performance of the peer group.

In an added twist, BP has extended the peer process even further. The three top-performing business units in a peer group have been made responsible for improving the performance of the bottom three. “We had ‘not invented here’ raised to an art form,” says Chase. With peer assist and peer challenge, he says, “What we have raised to an art form is that if I have a good idea, my first responsibility is to share it with my peers, and if I am performing poorly, I will get the peer group to help me.”

BP has achieved a powerful force in integration and knowledge sharing. According to Browne, “People do not learn, at least in a corporate environment, without a target. You can implore people to learn, and they will to some extent. But if you say, ‘Look, the learning is necessary in order to cut the cost of drilling a well by 10%,’ then they will learn with purpose.” What is special about BP’s peer groups is their effectiveness in transferring, sharing and leveraging cumulative learning through a direct link with performance.

Emotional Integration Through Shared Identity and Meaning

Ultimately, the acid test of organizational integration lies in collective action. A shared knowledge base must translate into coordinated and aligned action across the different parts of an organization, or it is only an expensive library. Unless peer relationships based on trust and friendship allow excellent collective execution, they create no value other than the comforts of an exclusive country club.15

It was the coordinating and aligning of actions that historically made hierarchy appear necessary. A common boss could align the activities of different company parts both through direct orders and through formal planning and control.16 Yet for most companies, hierarchy is no longer as effective — not only because it destroys front-line initiative and entrepreneurship, but also because of its inability to cope with uncertainty and rapid change.17 As they say at OgilvyOne, “While classical orchestras follow a conductor and a musical score in a rigid and formal manner, jazz bands — like Web marketeers — must be fluid, flexible, improvised and should always trust the requests and applause of their audience.”

Fluid and flexible collective action requires not only standardized infrastructure, shared knowledge and mutual trust, but also emotional integration through a common purpose and identity. Emotional integration has been the primary driver of success for companies such as Goldman Sachs.

Teamwork has always been a core value of the premier investment bank because, in the words of Goldman Sachs CEO Hank Paulson, “Quite simply, none of us is as smart as all of us.” The entrenched tradition of teamwork underlies the firm’s reputation for excellence in execution. “Everywhere and in every country around the world, when a Goldman Sachs banker walks into the room, all of Goldman Sachs comes with him or her,” says Robin Neustein, head of the firm’s Private Equity Group. “That, in turn, is the outcome of constant work on maintaining the one-firm identity and the internal challenge to be the best and help each other be the best.”

This emotional alignment among individuals — and between them and the firm — is the product of three distinct Goldman Sachs characteristics. First, the culture of success is built on a relentless focus on client relationships. Anyone who steps inside the firm can palpably feel this obsession with building and maintaining close and trusting relationships with clients. According to Neustein, “At Goldman Sachs, honor comes in the form of client service. … That is why if you try to make a lot of money without putting your client first, it is not a mark of success, it is a mark of shame.”

Stories of how the firm’s legendary leaders — Sidney Weinberg, Gus Levy, John Whitehead and others — went to extreme lengths, such as having six client dinners in one night, are told and retold. There is pride in being seen as a trusted adviser by the most influential politicians, industrialists and wealthy individuals around the world. However, rather than protecting individuals’ ownership of clients, client focus promotes integration because it explicitly emphasizes long-term retention. “Clients are simply in your custody,” John Weinberg, a second-generation leader of the firm, consistently reminded employees. “Someone before you established the relationship, and someone after you will carry it on.”

Although client focus provides a force for emotional integration with outsiders, pride in the quality of colleagues is an equally powerful force for emotional integration with insiders. As an internal survey conducted in 2000 revealed, 99% of Goldman Sachs employees were proud to work for the firm. Extraordinary levels of investment in recruiting only the most talented people around the globe — and then in continuous training and development for excellence — has, over decades, created the mystique about the firm as a magnet for talent, a mystique that reinforces the pride of belonging.

Second, it is not just the salary that has allowed the firm to become a magnet for talent. Inherently linked to the identity-shaping pride of belonging is a broader sense of purpose that emotionally connects each individual to the ethos of the firm.

Says Goldman Sachs president and co-chief coordinating officer John Thornton, “Anyone with any depth and talent has to ask the question, ‘What am I doing with my life?’ The purpose of my life is to use my talent for some larger and better purpose.” In Goldman Sachs, a broader purpose has historically been at the heart of that positive cycle of building emotional integration by linking purpose, talent and the pride of belonging.

The third contributor to emotional integration in Goldman Sachs is the one-firm mentality that is supported by, for example, doing the evaluation and selection of partners on a firmwide, rather than a divisional or product basis — and by a compensation system that until recently relied on the overall profit and loss to determine each partner’s fortunes. Each partner was allotted a fixed proportion of whatever the income for the year might be, with no discretionary payment based on any aspect of the partner’s or the unit’s performance. “We all had a piece of the action,” says Phil Murphy, co-head of investment management. “We didn’t care where the action came from. There was no disincentive to take that call from Hong Kong to help me out. … You and I didn’t care who got the credit for it; we knew we would both share the benefits.” After Goldman Sachs became a public company, the link between overall firm performance and each partner’s compensation was still important, although 60% rather than 100% of the rewards are now based on the common pool.

Entrepreneurial Activity and Horizontal Integration Co-Evolve

Our research demonstrates that individual and subunit autonomy co-evolve with horizontal integration in a dynamic process. It is in this dynamic evolution that horizontal integration differs from vertical integration. Instead of smothering bottom-up initiatives, horizontal integration creates a reinforcing process through which both autonomy and integration can flourish. (See “The Co-Evolution of Autonomy and Horizontal Integration.”) BP is typical of how the dynamic worked at all the companies we studied.

When John Browne was CEO of BP’s North American subsidiary, Sohio, he conducted a careful experiment to test his growing belief that a spirit of entrepreneurship was possible in a big company if the organization were broken up into relatively small, empowered units. He created a separate unit out of one operation that chronically lost money. To prevent any positive outcome from appearing purely a result of outstanding local leadership, he appointed managers of normal abilities. Allowed complete autonomy and freedom from the company’s central controls, the unit dramatically improved performance, confirming Browne’s theory.

When he became CEO in 1996, Browne acted on that lesson by restructuring BP into 150 business units and giving unit managers considerable freedom. The only conditions were that they respect certain “boundaries” — essentially, the core values of the company — and deliver on their performance contracts. Simultaneously, Browne downsized or completely eliminated much of the staff-supported, vertical, command-and-control infrastructure, abolishing the offices of country presidents and several functional departments in London.

To support the empowered and fully accountable business-unit leaders, he created the BP peer groups. Thus managers who ran similar businesses were assigned to help one another to improve both individual and collective performance.

The peer-assist process became effective in about two years as much of BP’s business-performance improvement began to flow from combining the business units’ entrepreneurial spirit with the peer groups’ knowledge sharing and mutual support. For example, when Polly Flinn — then a young manager from Amoco with no experience working outside the United States — became the managing director of BP’s retail business in Poland, she drew on active help from the marketing peer group and turned her business from a $20 million-per-year loss to a $6 million profit within 18 months.

The combination of empowerment and support improved business performance, producing two main results. First, top-level managers developed growing confidence in their strategy of delegating authority to the business-unit leaders. Second, the company had more resources to invest in developing the integration infrastructure, including IT systems, and in building conversation and communication mechanisms. Those investments further strengthened the mechanisms and the processes of horizontal integration.

As the symbiotic effects of autonomy and horizontal integration evolved, a culture of collaboration gradually emerged. Rodney Chase described the culture change thus: “In our personal lives — as fathers, mothers, brothers or sisters — we know how much we like to help someone close to us to succeed. Why didn’t we believe that the same can happen in our business lives? That is the breakthrough, and you get there when people take enormous pride in helping their colleagues to succeed.”

And as the culture evolved, managers’ self-confidence grew. They set themselves increasingly tough targets and achieved them through their own initiatives and the support of their peers.18 Their success strengthened their sense of autonomy and their spirit of entrepreneurship. Moreover, the culture led to the reinforcement of mutual trust and friendship — and the peer-group processes of horizontal integration.

A cautionary note: The symbiotic co-evolution of autonomy and horizontal integration takes time to mature. Vertical integration — bringing different units under a common boss and a common planning and control system — can be implemented relatively quickly. But to develop people’s self-confidence and to build trust and friendship can be achieved only through persistent action and reinforcement over time. For senior executives, that is the greatest challenge in building horizontal integration: Although they have to be relentless in driving the process, they also have to be patient about results. For those who respond well to that challenge, the ultimate benefits are durable enhancement of organizational capability and sustainable improvement of business performance.

References

1. For a theory-grounded analysis of the tension, see R.P. Rumelt, “Inertia and Transformation,” in “Resource-Based and Evolutionary Theories of the Firm,” ed. C.M. Montgomery (Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995), 101–132.

2. For a rich description and analysis of that tension in the context of large, diversified global companies, see C.K. Prahalad and Y. Doz, “The Multinational Mission: Balancing Local Demands and Global Vision” (New York: Free Press, 1987).

3. For a description of companies that followed the strategy of creating small units to rekindle front-line entrepreneurship, see S. Ghoshal and C.A. Bartlett, “The Individualized Corporation: A Fundamentally New Approach to Management” (New York: HarperCollins, 1997).

4. That sequential process of performance improvement — first building the strength of the units and then building integration mechanisms across them — was described in S. Ghoshal and C.A. Bartlett, “Rebuilding Behavioral Context: A Blueprint for Corporate Renewal,” Sloan Management Review 37 (winter 1996): 23–36.

5. For a classic analysis of that need, see P.R. Lawrence and J.W. Lorsch, “Organization and Environment” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1967).

6. The impact of the Web on integration opportunities can be inferred from the analysis of R.L. Daft and R.H. Lengel, “Information Richness: A New Approach to Managerial Information Processing and Organizational Design,” in vol. 6, “Research in Organizational Behavior,” eds. L.L. Cummings and B.M. Staw (Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press, 1984), 191–234. For a focused discussion on the role of IT in facilitating communication, see A.D. Shulman, “Putting Group Information Technology in Its Place: Communication and Good Work Group Performance,” in “Handbook of Organization Studies,” eds. S.R. Clegg, C. Hardy and W.R. Nord (London: Sage, 1996), 357–374.

7. See A. Edstrom and J.R. Galbraith, “Transfer of Managers as a Coordination and Control Strategy in Multinational Organizations,” Administrative Science Quarterly 22 (June 1977): 248–263.

8. The important but often ignored role of middle managers in organizational integration has been described in R.M. Kanter, “The Change Masters: Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the American Corporation” (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983).

9. Such vertical processes of organizational integration lay at the heart of the divisional organizational model. For one of the richest and best-known expositions, see A.D. Chandler, “Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of American Industrial Enterprise” (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1962).

10. See J. Galbraith, “Designing Complex Organizations” (Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley, 1973); and for a discussion of horizontal mechanisms in large, global companies, see C.A. Bartlett and S. Ghoshal, “Managing Across Borders: The Transnational Solution” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1988).

11. We focus on the challenges of internal integration across existing and established units within large, complex organizations. Clearly, there are other important integration contexts — such as integrating strategic alliances, joint ventures, upstream and downstream partners on the value chain and so on. We do not address those contexts here, but interested readers can find comprehensive discussions elsewhere: for example, in Y. Doz and G. Hamel, “Alliance Advantage: The Art of Creating Value Through Partnering” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998). Within the organization, integration of new ventures poses unique challenges. An outstanding analysis of the topic appears in C.M. Christensen, “The Innovator’s Dilemma” (New York: HarperBusiness, 1997).

12. Several authors have highlighted the need of a social structure to support IT-based systems for effective knowledge management in distributed organizations. See, for example, the discussion on social ecology in V. Govindarajan and A. Gupta, “The Quest for Global Dominance: Transforming Global Presence Into Global Competitive Advantage” (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001).

13. See, for example, M.T. Hansen and B. Von Oetinger, “Introducing T-Shaped Managers: Knowledge Management’s Next Generation,” Harvard Business Review 79 (March 2001): 106–116.

14. This is essentially a sophisticated use of social control. See W.G. Ouchi, “A Conceptual Framework for the Design of Organizational Control Mechanisms,” Management Science 25 (September 1979): 833–848.

15. See J. Pfeffer and R.I. Sutton, “The Knowing-Doing Gap: How Smart Companies Turn Knowledge Into Action” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000).

16. The benefits of hierarchy provide the theoretical basis for influential economic analysis of why companies exist, one of the most well-known being O.E. Williamson, “Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications” (New York: Free Press, 1975).

17. For a discussion on the limitations of a hierarchical system in coping with uncertainty and rapid change, see S.L. Brown and K.M. Eisenhardt, “Competing on the Edge: Strategy as Structured Chaos” (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998).

18. See A. Bandura, “Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control” (New York: Freeman, 1997).