A Little Rudeness Goes a Long Way

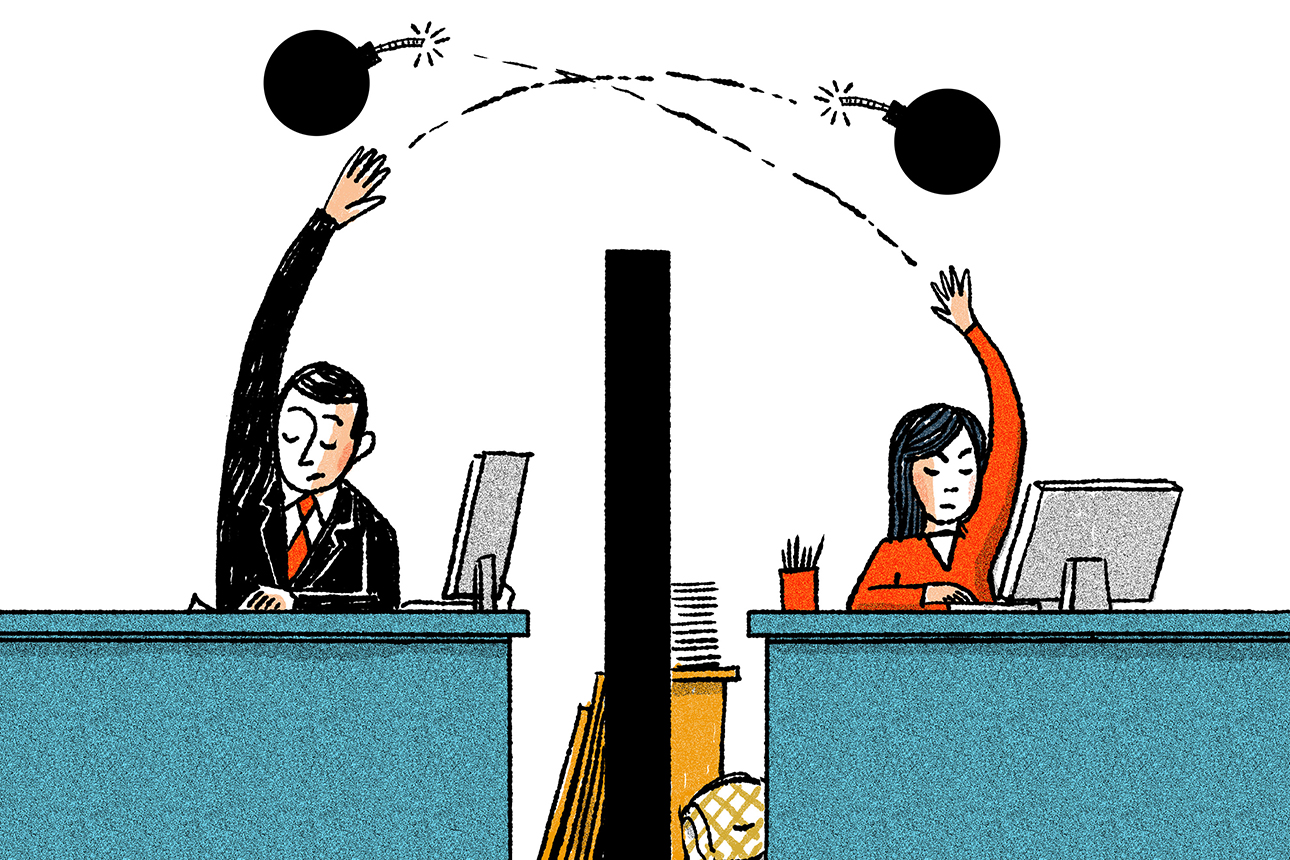

How to stop incivility from spreading in your organization.

Robert Nuebecker/theispot.com

As the COVID-19 pandemic lingers, so too do exceedingly high levels of stress and uncertainty in the workforce. Hopes for an imminent return to a “normal” workplace have evaporated. Even in the best of circumstances, companies and their employees face many unknowns: How will they fare under hybrid work models longer term? How else will they need to adapt to survive and compete in a changing landscape? Will their businesses weather other unexpected crises? If they do, how will roles change? Whose jobs will be safe?

All of this takes a psychological and behavioral toll: Research shows that uncertain environments make people more likely to engage in rude, uncivil, and disrespectful behavior — and they make targets of incivility more vulnerable to it.1

That’s more detrimental to organizations than you might think. Employees who experience incivility at work perform worse in their jobs, are less helpful to colleagues, and are more likely to steal from their employer.2 Rudeness also hurts employee retention and the bottom line. According to one estimate, handling a single incident of rudeness can cost an organization more than $25,000.3

The vast majority of employees experience rudeness at work. In one study, 98% of employees reported being insulted, interrupted, ignored, or treated rudely in various other ways.4 As a result, researchers have described workplace rudeness as an epidemic. But our recent findings suggest that closer to 70% of employees experience incivility — still a lot, but not quite as many as previously thought — and that it spreads more like an endemic disease, wreaking havoc locally. In many workplaces we studied, outbreaks were traced to a single source: One office jerk spewed incivility like a contaminated water pump.5

Although few people behave rudely at work, the high percentage of workers who experience incivility means its impact is widespread, even if the perpetrators aren’t. And yet incivility is relationship-based.

References (22)

1. C.C. Rosen, N. Dimotakis, M.S. Cole, et al., “When Challenges Hinder: An Investigation of When and How Challenge Stressors Impact Employee Outcomes,” Journal of Applied Psychology 105, no. 10 (October 2020): 1181-1206; and S.G. Taylor and D.H. Kluemper, “Linking Perceptions of Role Stress and Incivility to Workplace Aggression: The Moderating Role of Personality,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 17, no. 3 (July 2012): 316-329.

2. C.L. Porath and A. Erez, “Does Rudeness Really Matter? The Effects of Rudeness on Task Performance and Helpfulness,” Academy of Management Journal 50, no. 5 (October 2007): 1181-1197; S.G. Taylor, A.G. Bedeian, and D.H. Kluemper, “Linking Workplace Incivility to Citizenship Performance: The Combined Effects of Affective Commitment and Conscientiousness,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 33, no. 7 (October 2012): 878-893; and Taylor and Kluemper, “Linking Perceptions,” 316-329.