Bringing Open Innovation to Services

In recent years, open innovation has been changing the way many companies think about developing products. But open innovation can — and should — apply to services, too.

Image courtesy of Flickr user Jinho.Jung

Back in 2004, I sat in Paul Horn’s office at IBM. Horn was at the time IBM’s senior vice president of research, in charge of IBM’s 3,000 research staff. We had a wonderful conversation about innovation, and the many successes IBM had obtained from its research activities. At the end of our time, I asked Horn a final question: What is your biggest problem today?

Horn told me that his biggest problem was that his research activities were geared to support a company that made products: computer systems, servers, mainframes and software. But most of IBM’s revenues were coming from services, not from its products. “I can’t sustain a significant research activity at IBM if our research is not relevant to more than half of the company’s revenues going forward,” Horn stated.

The Leading Question

How does open innovation apply to service businesses?

Findings

- Many open innovation concepts apply readily to services.

- One way companies can move toward open innovation in services is by working closely with customers to develop new solutions.

- Product-oriented companies face organizational challenges in moving to a greater emphasis on services.

The challenge Horn articulated in that conversation was not unique to IBM. In fact, the challenge of how to innovate in services is one that faces not just individual companies but also entire countries. The world’s developed economies are increasingly oriented around services: Services comprise more than 70% of aggregate gross domestic product and employment in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries.1 In countries such as the United States, products represent a smaller and smaller share of the economic pie — particularly as China and other lower-wage countries rise in manufacturing. An important problem for advanced economies is that we know much less about how to innovate in services than about how to develop new products and technologies.

Rethinking Business — From a Service Perspective

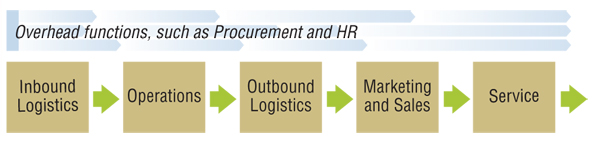

Consider the classic formulation of a business as a value chain of economic activities that add value to a product. Michael Porter’s well-known book Competitive Advantage includes an illustration of this type of value chain.2 In Porter’s depiction of a value chain, inputs enter the business and are transformed into outputs through a series of processes. Some of the processes are core manufacturing activities (inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics), while others are activities supporting manufacturing (human resources, technology development, procurement). But in Porter’s depiction of the value chain, the product is the implicit star. “Service” comes only at the very end of his diagram, just before the product gets to the customer. (See “The Role of Service in a Traditional Value Chain.”) Service’s role is, by implication, limited to enabling the product’s sale or keeping the product operating once it is purchased.

Porter’s value chain has been a powerful tool for conceptualizing businesses and how to innovate within them. It is widely taught in business schools around the world. It is installed in the operating procedures of myriad companies as well. And it reflects the mindset of many executives toward their businesses: The important work happens with the product.

The Role Of Service In A Traditional Value Chain

However, some important contrary voices offer a different perspective. The late Harvard Business School professor Theodore Levitt is said to have pointed out to his students that customers often do not want the product itself, but rather want the effect that the product produces. In his famous example, customers do not want a drill; they want the holes that the drill will make. Peter Drucker made much the same observation: “What the customer buys and considers value is never a product. It is always utility — that is, what a product does for him.”3

Thinking about your business as a service business requires moving away from Porter’s product-oriented value chain and embracing Levitt’s and Drucker’s alternative approach to the customer. For services, the value chain must be replaced by a different kind of graphic — one with creating customer experience as its focus. (See “Creating the Customer’s Experience: A Services Value Web.”)

In a services value web like the one shown, there is not a simple linear process of material inputs being transformed into outputs and then shipped off to the customer. Instead, there is an iterative process that involves the customer and results in a customer experience. The process begins by engaging the customer, either with an open-ended inquiry about his or her needs or by extending a particular service offering. Engagement need not mean a take-it-or-leave-it proposition to the customer; instead, the customer often is invited to co-create the service.4 In the process of engagement and co-creation, tacit knowledge is elicited from the customer (and the customer often learns tacit knowledge from the provider as well). The provider may use this additional knowledge to design or refine experience points where the customer directly encounters outputs from the service. With those experience points identified, the service offering is then made to the customer (or an existing offer is further developed). A customer experience is produced from this web of activity. The surrounding environment reminds us that the provider need not provide all of the service itself; rather, the provider can coordinate the delivery of both internal and external services to the customer.

Here’s how this cycle might work in practice. A prospective customer contacts a service provider with a problem he or she would like to solve. The provider has some relevant expertise. They begin a discussion to see if there is an overlap between the problem to be solved and the provider’s expertise. The provider is careful to ask open-ended questions to diagnose the problem correctly, while the customer is contributing additional information about his or her specific situation and context. (This is where the tacit knowledge begins to be shared.) Some points of contact may be developed, such as a proposal for the work to be done. Such points of contact clarify the problem and the provider’s ability to solve it; they also create new shared experiences between the customer and provider. An offer is made by the provider, and the customer accepts it or supplies additional information about what further needs he or she has that the provider has not yet addressed. And so the cycle might continue until it reaches an acceptance or a refusal by the customer.

Creating The Customer’s Experience: A Services Value Web

In my earlier work, I argued that companies should organize their innovation processes to become more open to external knowledge and ideas. I also suggested that companies let more of their internal ideas and knowledge flow to the outside, when they were not being utilized within the company.5 Yet my initial discussion of open innovation contrasted it to traditional internal R&D and technology and product development; this had the effect of placing the focus more on product and technology innovation than on service innovation.

Open innovation works somewhat differently in services businesses, in part because the role of the customer is different in such businesses. Services are intangible by nature, so that customers often cannot specify exactly what they want. It is often much harder to measure the services that are delivered. And different customers might experience the same service differently.

In addition, innovation processes work differently in services. Few companies have formal R&D operations for the services they provide. The formal stage-gate processes used in many large companies to advance new product development projects from inception to the market likely are not used. The customer may need to participate throughout the innovation process. Tacit knowledge may only emerge during the innovation process, so that one cannot collect it in advance. Even the people in the process may differ; IBM and Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center, for example, hire Ph.D.s in fields such as sociology, anthropology and economics as part of their services research staff.

Yet every company that sells services needs innovation to differentiate and to grow. Finding these paths to growth requires new initiatives that not only improve a currently offered service but contemplate extensions of that service, or even entirely new service offerings. By grouping these growth and differentiation initiatives together, one can create a portfolio of projects that are every bit as innovative as those of product and technology companies. Utilizing open innovation can help companies achieve the growth in service revenues they seek.

How Open Innovation Applies to Services

Some of the concepts of open innovation apply readily to service innovation. Openness generally refers to ways of sharing with others and inviting their participation. In the open innovation model, there are two complementary kinds of openness. One is “outside in,” where a company makes greater use of external ideas and technologies in its own business. Openness in this context means overcoming the “not invented here” syndrome, where the company monopolizes the source of its innovations, and instead welcoming new external contributions.

The other kind of openness is “inside out,” in which a company allows some of its own ideas, technologies or processes to be used by other businesses. Openness here means overcoming the “not sold here” syndrome, in which the company monopolizes the use of its innovations, prohibiting use outside of its own business. Opening up the inside means that revenues from external use of a company’s ideas are welcomed. Let’s consider each kind of openness in turn, as it applies to service innovation.

Bringing the Outside In: LEGO. Companies can do more to involve customers in their innovation processes than simply watch them. Some companies, like LEGO, have had great success in letting customers create designs.6 In LEGO’s case, an early example of this phenomenon was LEGO Mindstorms, in which the company included programmable motors with the plastic parts. This allowed consumers to build LEGO designs that could move. Well, someone hacked into the software that came with these motors to make unauthorized modifications to get the LEGOs to perform more functions. Initially, the LEGO people thought that this was illegal and should be stopped.

After further consideration, the company reversed course. It opened up its software so that anyone could modify it and watched what customers decided to create. One outcome from this radically open approach was that an entire middle-school curriculum was developed in the United States to teach children robotics, using LEGOs. Students were now learning about programming and design, building LEGO vehicles to follow a track on the floor or shoot a ball through a basket. There were even competitions created in which a set of challenges were given to all competing entrants. In this way, LEGO products have given rise to a services industry focused on middle-school science and technology education.

Taking the Inside Out: Amazon.com. Amazon has not only created open service innovation by bringing the outside in — think of customer reviews on Amazon.com and third parties selling products via Amazon’s site — but also by taking the inside out. As Amazon grew increasingly successful, it began to partner with large retailers that wanted their own websites to offer merchandise. The retailers realized that Amazon knew a lot about running a retail website and wanted to hire that experience and put it to work for themselves.

Amazon could have treated its expertise in this area as a trade secret and refused to offer its knowledge to others. Instead, Amazon saw a new business opportunity to create more value from its knowledge of Internet retailing and website infrastructure. Amazon helped third-party retailers develop their own websites. Then the company went further, offering to host these third-party sites on its own servers and thus becoming the infrastructure supplier to those retailers. In some cases, Amazon would even perform the merchandising and fulfillment portions of the transaction for the retailer. This was a powerful way for Amazon to get paid for its knowledge — taking the infrastructure it had built for itself out into the marketplace so other companies could utilize it.

More recently, Amazon has created yet another business that exploits its knowledge. Amazon offers cloud computing services to potential customers. Many companies that are much smaller than Amazon lack the volume of business and the expertise to develop and manage their own information technology equipment and staff. For such customers, Amazon will host a company’s IT functions and charge only for those services actually consumed. For customers, what was a large fixed investment in an area where they lack much relevant expertise can be converted to a variable expense that is managed by someone far more experienced and knowledgeable. Through its recognition that some of its own knowledge and infrastructure could be leveraged to build open services, Amazon has built a stronger, more valuable business for itself.

How to Foster Open Service Innovation

Granted, it isn’t easy to move your company toward open service innovation — particularly if you have had a product-focused company. (See “Barriers to Service Innovation in a Product-Oriented Company.”) Focusing on the value to your customer is the right way to start the journey toward a more services-oriented approach to your business.

Work closely with customers to develop new solutions. One way to do this is with pilot projects that cause you to team up with a particular customer to solve a particular problem. IBM has a program along these lines called First-of-a-Kind. The customer and IBM both agree to enter into the project, with both sharing the knowledge that comes out of it. The customer gets a good solution to its problem ahead of competitors, while IBM gets the right to reuse the solution in selling to other customers.

Focus offers on utility, rather than the product. Xerox has a services program called managed print services, in which the company offers to manage all of a customer’s copiers and printers. The customer pays only a fixed price per page of output, while all of the acquisition, installation, operation, maintenance and replacement activities are managed by Xerox. Levitt would no doubt have approved: People don’t really want copiers, they want copies. Xerox’s offer also changes what was previously a fixed cost into a variable cost for the customer. It is more capital-efficient for the customer and provides a better career path for employees previously charged with managing copiers and printers in the customer’s organization. Procter & Gamble entered into such an arrangement with Xerox and estimates that it will save more than 25% on its printing and copying costs in the process.

Embed your company in your customer’s organization. A third, related way to transform yourself into a more effective services business is to embed yourself in your customer’s organization and its processes. United Parcel Service offers to take over the entire shipping function of its customers, so that UPS handles all of the shipments for its customers, whether they go by UPS, the U.S. Postal Service or even FedEx. In the process, UPS sees a great deal more of its customers’ processes that require shipping. This provides new customer insight for new services by UPS. For example, the company now offers its customers logistics help with inbound supplies from the company’s supply chain. Previously, UPS had no visibility into the customer’s supply chain. With the new services offering, it now can offer new services, increase its share of wallet with the customer and find new sources of revenue for itself.

Returning to Paul Horn and IBM, IBM has launched a variety of initiatives to advance its services offerings to its customers. One internal initiative to find new business opportunities, the Innovation Jam, was successful enough that IBM created a new service offering around it for its customers. IBM’s understanding of its customers’ business models and its research into improving its own bidding processes in sales have earned tens of millions of dollars for the company.7 The Smarter Planet initiative of IBM incorporates the company’s technologies with its services to provide new business opportunities in applications such as renewable energy, urban planning, water purification and management and drug development. Today, IBM Research has hundreds of its staff focused on research for its large and growing services businesses. While they still advance hardware and software, these researchers also study how customers use technology and how best to design processes for customers to get the most out of technology.

As companies like IBM, Xerox and UPS are discovering, services help unlock the utility customers want from a product. When you provide real value to your customers, they are less likely to switch to competitors that offer a slightly lower price for the product. Services also differentiate you from your competitors. When you get to know your customers’ problems and processes better, you will get new knowledge for new improvements and services that your competitors won’t even know about. Innovating in services is an important route to new revenues, increased margins and happier customers in a services-led economy. And that will bring new growth and more jobs to our economy in the process.

References (8)

1. OECD, “Productivity Growth in Services,” in “OECD Factbook 2008: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics” (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2008). See also A. Wölfl, “The Service Economy in OECD Countries: OECD/Centre d’études Prospectives et d’Informations Internationals (CEPII),” OECD Science Technology and Industry Working Papers, working paper 2005/3, OECD Publishing, Paris, February 11, 2005.

2. M.E. Porter, “Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance” (New York: Free Press, 1985), 37.

Comment (1)

Lance Bettencourt