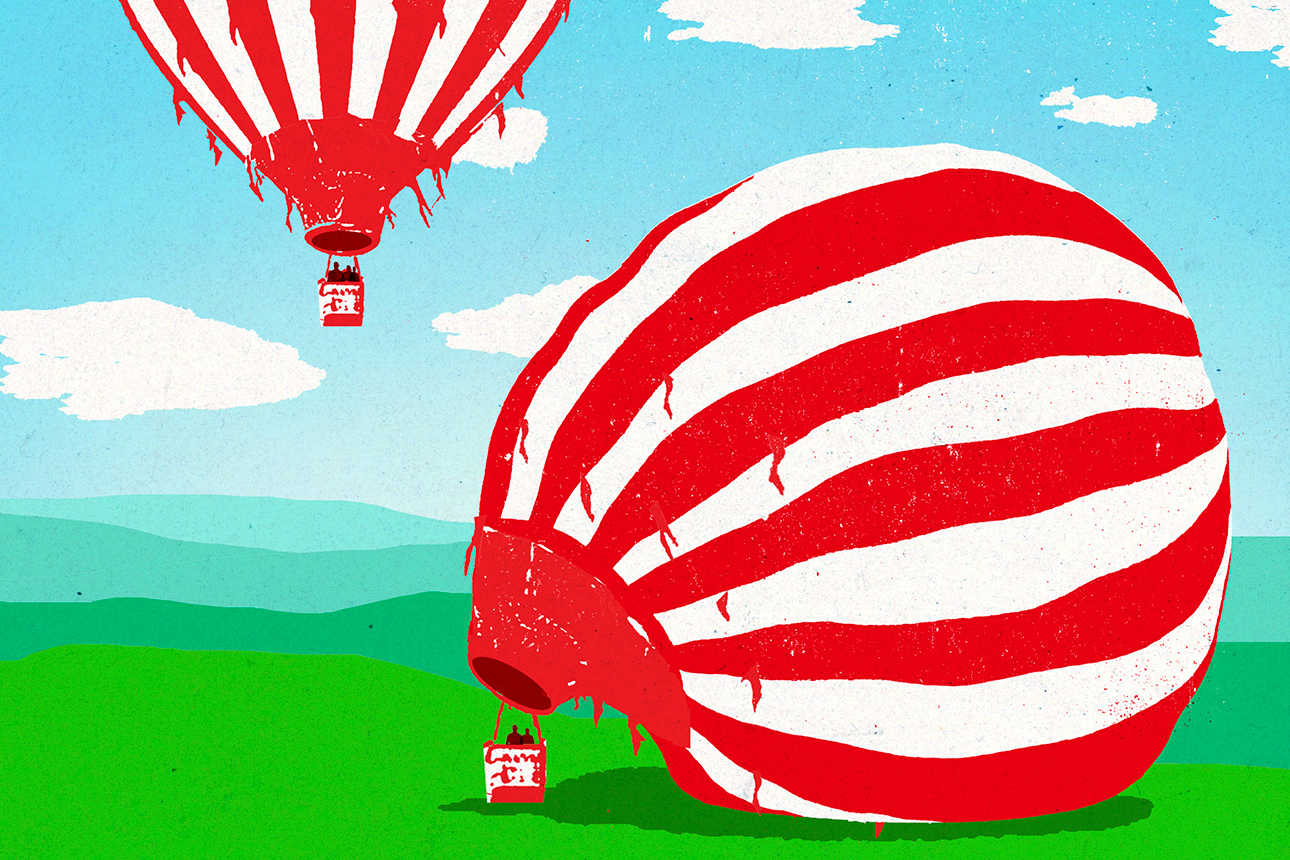

How Would-Be Category Kings Become Commoners

Innovative companies may succeed in pioneering new markets, but often fail to dominate the categories they create.

Image courtesy of Richard Mia/theispot.com

Starting any business is hard, but creating a new category of business with a completely new model is a high-wire act. Companies have to convince investors, customers, the media, analysts, and others that something the world has long managed without is now a necessity and legitimately constitutes a new business category. While educating and selling the market on this new category, there’s also a business to build and a whole new business model to formulate. Pulling this off is like delivering a nonstop TED Talk while inventing the light bulb and building General Electric all at the same time.

Many people feel it’s a challenge worth taking. Category creation is the holy grail in business. Companies that succeed at creating entirely new markets, industries, or product categories — like Airbnb, DocuSign, and Salesforce — generate wealth beyond their founders’ wildest dreams. The spoils are so great that the winners are often referred to as category kings. Over time, their brand name becomes virtually synonymous with their category, effectively barring new entrants.

Once a king emerges, would-be competitors become also-rans, or commoners. These businesses find it increasingly hard to maintain support: Media and analyst attention dries up, leading to less investment and fewer customers. Ultimately, they are sold for parts or shut down altogether, like Napster or AltaVista.

Getting this high-wire act right is critical. Competition in new categories is more intense than ever. The cost of starting a digital company has shrunk by 90% in the two decades since the dot-com crash, thanks to the emergence of open-source software, cheap cloud computing, and social media platforms that offer low-cost advertising and free publicity.1 Low startup costs mean more startups, more categories, and more competitors vying for consumers’ limited attention.

References (15)

1. R. McDonald, A. Burke, E. Franking, et al., “Floodgate: On the Hunt for Thunder Lizards,” Harvard Business School case no. 617-044 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2017).

2. R. McDonald, “Category Kings or Commoners? Market-Shaping and Its Consequences in Nascent Categories,” working paper 16-095, Harvard Business School, Boston, January 2020.