Is Your Company Ready for Open Innovation?

The right open innovation strategy can yield performance benefits — but first your company needs to overcome “not-invented-here” and “not-sold-here” attitudes.

To foster open innovation, Procter & Gamble set up incentive systems to reduce not-invented-here attitudes among its employees.

Image courtesy of Procter & Gamble.

In the face of challenging economic conditions and growing international competition, many industrial companies are attempting to capture additional value from their technologies. In particular, many companies are trying to profit from open innovation, which involves actively collaborating with external partners throughout the innovation process. Many industrial companies now acquire technology from external sources in order to strengthen and speed up their internal innovation processes — an approach we call inbound open innovation. Companies also increasingly transfer some of their own proprietary technology to other companies by means such as licensing, to achieve various monetary and nonmonetary benefits.1 We call that approach outbound open innovation.

Several pioneering companies, such as Procter & Gamble, Dow Chemical, IBM and Hewlett-Packard, have strongly profited from pursuing open innovation strategies.2 Following these successful examples, managers have focused on the need to establish open innovation strategies based on active collaborations with external partners.3

The Leading Question

How can large companies successfully implement open innovation strategies?

Findings

- Employee attitudes that favor internal innovation often impede open innovation approaches.

- Companies whose employees have favorable attitudes toward both

inbound and outbound open innovation achieve the highest average return on sales. - Managers should revise incentive systems to support open innovation methods.

However, many managers have insufficiently considered the challenges of implementing these strategies. Without a successful implementation process, the potential benefits of open innovation strategies will not materialize, and a company may lose some of its technological competitive advantage.4

The implementation of open innovation strategies is often impeded by employee attitudes that favor internal innovation. Such employee attitudes can be embedded in a company’s corporate culture, which has developed over time and may strongly affect employee behavior. Specifically, many companies’ corporate cultures are characterized by “not-invented-here” tendencies — in other words, negative attitudes toward inbound open innovation. Employees with “not-invented-here” tendencies do not want to acquire technology from external sources and instead want to focus on internally developing new technological knowledge. Not-invented-here attitudes may stem from limited or negative experiences with inward technology transfer and from inappropriate incentive systems. Before being able to successfully implement its inbound open innovation strategy, Procter & Gamble set up incentive systems to reduce not-invented-here attitudes among its employees.5

“Not-sold-here” tendencies describe similar negative attitudes found in many corporate cultures with respect to transferring company technology. These attitudes toward outbound open innovation may result from fear of strengthening competitors by selling corporate “crown jewels” — in other words, competitively relevant technology.6 Not-sold-here attitudes may be strengthened by limited experience with outward technology transfer and the inefficiencies in the markets for technological knowledge. To facilitate the implementation of outbound open innovation, Procter & Gamble has taken several approaches to reducing employees’ not-sold-here attitudes. For instance, it has established reward systems that value the identification of licensing opportunities.7

Not-invented-here and not-sold-here attitudes are frequently well intended. Employees are often convinced of the superiority of exclusively internal innovation. In many situations, however, companies simply cannot internally develop all relevant technological knowledge. Similarly, a focus only on internally applying company technology may result in a limited exploitation of companies’ technology portfolios.

Four Distinct Types of Open Innovation Cultures

The results of a large-scale benchmarking study revealed four groups of companies with different attitudes toward transferring technology through open innovation. (See “About the Research.”) The relatively large first group, which we call Technology Isolationists, comprised 36% of the companies in the study’s sample. Technology Isolationists are characterized by high levels of both not-invented-here and not-sold-here attitudes. These companies focus on closed innovation without paying particular attention to open innovation initiatives.

The second group, Technology Fountains, accounted for 26.6% of the companies in the sample. These companies are sources of technological knowledge, which they partly transfer to other companies. But they are still characterized by strong not-invented-here attitudes. An example of this group is a relatively large chemical company that actively licenses some of its own technology to external partners based on a strong internal technology portfolio. However, the company is still characterized by considerable not-invented-here tendencies, which have strongly limited the implementation of inbound open innovation.

The third group of companies, which we call Technology Sponges, comprised 21.3% of the companies in the sample. Technology Sponges actively absorb external technology, but they do not transfer a lot of their own technology to external partners. An example of this group is a pharmaceutical company that actively relies on inbound open innovation; it collaborates with other pharmaceutical companies, small biotechnology companies and several research institutes and universities. The company also pursues a relatively open outbound strategy, but the implementation of that strategy is strongly impeded by not-sold-here tendencies. As a result, the company is assessing different possible approaches to reducing its employees’ not-sold-here attitudes.

The final group of companies, the Technology Brokers, is relatively small; it accounted for 16.1% of the companies in the sample. Technology Brokers actively pursue both inbound and outbound open innovation and have a very limited level of not-invented-here and not-sold-here tendencies. The companies’ employees have acknowledged the benefits of opening up the innovation process because they have already experienced the positive effects of open innovation initiatives. An example of this group is a medium-sized electronics company that has strongly opened up its innovation process. It uses a variety of contractual modes for collaborating with external partners, including alliances, licensing deals and cross-licensing agreements. These collaborations involve active inward and outward technology transfer.

Implications for Performance

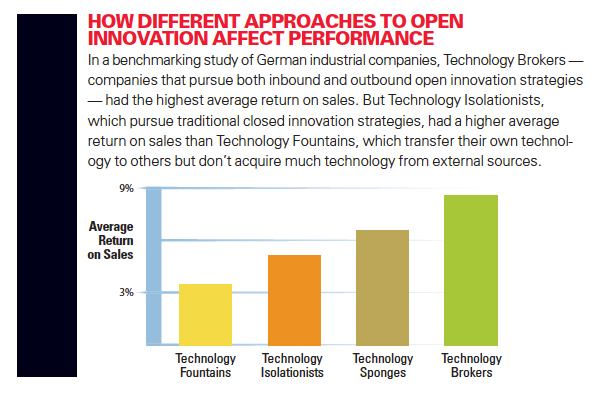

The companies in the four groups exhibit different levels of financial performance. Specifically, the benchmarking study showed a significant difference in the average return on sales. The lowest average return on sales was found among the Technology Fountains. These companies focus on internal technology development rather than external technology sourcing, but they actively transfer some of their own technology. This exclusive focus on outbound open innovation combined with a strong reluctance to implement inbound open innovation seems to be detrimental to financial performance. In particular, these findings illustrate the risks of outbound open innovation, which may stem from strengthening competitors by transferring corporate crown jewels. If companies only open up their innovation processes toward outbound open innovation, they fail to profit from inbound open innovation, and this unbalanced openness toward outward technology transfer can be dangerous.

How Different Approaches To Open Innovation Affect Performance

Technology Isolationists, the companies that hardly rely on open innovation at all, had an average return on sales that was higher than that of the Technology Fountains — but lower than that of the Technology Sponges or the Technology Brokers. While Technology Isolationists forego substantial benefits from open innovation, their traditional closed innovation approach still appears to be superior to an exclusive focus on outbound open innovation.

In contrast, the Technology Sponges achieved a higher return on sales than either the Technology Fountains or the Technology Isolationists. Technology Sponges capture the benefits from inbound open innovation, but they are very reluctant to pursue outbound open innovation. This finding further highlights that inbound open innovation is a requirement for many companies. Inbound open innovation reduces the risks of product development, and it may speed up the product development process. These benefits seem to outweigh potential negative effects.

The highest average return on sales was achieved by the Technology Brokers. These companies implement a balanced approach toward open innovation; their employees are open toward inbound and outbound open innovation, and the companies engage in active inward and outward technology transfer. These companies’ high average level of return on sales points to important benefits from implementing an open innovation strategy that combines inbound and outbound processes. In particular, there may be synergies from simultaneously relying on inbound and outbound open innovation. For instance, some successful open innovators emphasized in interviews the additional opportunities for outbound open innovation that they identified through inbound open innovation processes — and vice versa.

Transforming Employee Attitudes

The results of the benchmarking study underscore the need to change employee attitudes if managers aim to implement open innovation strategies. The examples of pioneering companies that are benefiting from open innovation suggest the following five-step procedure for reducing potential not-invented-here and not-sold-here tendencies.

1. Managers need to communicate the open innovation strategy throughout the company. In many companies, open innovation initiatives contrast with traditional closed innovation strategies. It is therefore critical that the open innovation strategy and its particular focus on inbound and outbound processes are communicated to all employees involved in innovation. In particular, managers need to communicate the benefits that may be achieved by opening up the innovation process.

2. The open innovation initiative needs the support of top executives. To reduce employee biases against technology transfer, the support of high-ranking managers is critical. Top executives may serve as champions and promoters of open innovation.

3. Managers have to establish suitable incentive systems. In many companies, the emergence of not-invented-here and not-sold-here attitudes is supported by incentive systems that favor internal innovation, such as incentives for patenting internally developed technologies. Managers may revise incentive systems to reduce emphasis on internal innovation, or they may design particular monetary and non-monetary incentive mechanisms in support of technology transfer, such as an open innovation award.

4. Companies can design their organizational structures to ease open innovation. Many pioneering companies have established organizational structures that encourage and systematize open innovation initiatives. While some companies take an integrative approach and establish dedicated functions for coordinating inbound and outbound open innovation, other companies have set up more specific units for managing out-licensing activities or strategic R&D alliances. Both organizational approaches help to reduce employees’ reluctance to implement open innovation strategies.

5. Managers need to institutionalize open technology transfer attitudes in the corporate culture. After completing the previous steps, managers should ensure that their company achieves some quick-win deals that help to demonstrate the benefits of open innovation within the organization. Such positive experiences with open innovation are an excellent way to reduce not-invented-here and not-sold-here attitudes.

Meeting the Challenges Ahead

Many companies have established open innovation strategies but fail to successfully implement them. Our benchmarking study found that implementation challenges for open innovation strategies derive from not-invented-here and not-sold-here attitudes among many companies’ employees. These findings suggest that managers should not oversimplify the realization of open innovation opportunities by excessively focusing on strategy formulation. Instead, if companies aim to profit from open innovation, unbiased employee attitudes are a critical foundation — and changing employee attitudes requires some time. The positive performance effects of some open innovation strategies show that a successful implementation of inbound and outbound open innovation processes can be beneficial. And the need for implementing open innovation is expected to gain further importance in the future — because an exclusive focus on internal innovation will not be a viable option.

References (7)

1. O. Alexy, P. Criscuolo and A. Salter, “Does IP Strategy Have to Cripple Open Innovation?,” MIT Sloan Management Review 51, no. 1 (2009): 71-77.

2. L. Huston and N. Sakkab, “Connect and Develop: Inside Procter & Gamble’s New Model for Innovation,” Harvard Business Review 84, no. 3 (2006): 58-66; and U. Lichtenthaler, “Open Innovation: Past Research, Current Debates, and Future Directions,” Academy of Management Perspectives 25, no. 1 (2011): 75-93.