When Supplier Partnerships Aren’t

Dual accountability between a buyer and its strategic suppliers, through tools such as a Two-Way Scorecard, is a new and tangible approach to improving supply chain relationships.

Ask an executive to describe how his or her company interacts with its suppliers, and it usually doesn’t take long before such words as “relationship,” “partnership” or even “marriage” come up. Indeed, most executives liken their supply chain interactions to a personal relationship, with each partner bringing complementary strengths to create a bond that is mutually fulfilling over time.

If there is one truism about any relationship, however, it is that open, honest communication is required ofboth parties. Yet in some of the most “strategic” supplier-buyer relationships, good communication is absent. A review of the popular literature on supply chain management is telling. There is plenty of discussion of measuring supplier performance; of the need for “soft” supplier metrics such as service and innovation in addition to “hard” metrics such as cost and quality; and of the need for sophisticated models to evaluate supplier performance. But where is the discussion of holding thebuyer accountable for its end of the bargain? In most cases, there are no supply chain metrics for buyers. Why should the buyer be accountable for anything, goes the reasoning — aren’t they spending the money, after all?

Some progressive executives today are employing a different approach. They recognize that buyers have as much influence as suppliers on the success — or failure — of a supply chain relationship. These executives are translating this notion into measurable reality with mechanisms that emphasizedual accountability by creating tools that contain metrics for which both parties are accountable. Dual accountability requires a fundamental shift in the psychology of buyer-supplier relationships. Not only is tangible accountability demanded from both partners, but suppliers and buyers must also show greater communication and openness, as well as a willingness to trust in the presence of professional vulnerability — much like a marriage.

This article presents dual accountability, realized through a Two-Way Scorecard and other methods, as a central mechanism to improve strategic supply chain partnerships. The article explores the genesis of the dual accountability concept, outlines the benefits — which range from decreased risk to improved reputation to lower total cost — and illustrates how dual accountability can be profitably applied by suppliers and buyers working together. (See “About the Research.”)

The Emergence of Supplier Performance Management

Over the past two decades, the role of the procurement office has fundamentally changed in most large organizations. In the early days, interactions with suppliers (indeed, the procurement office’s entire emphasis) turned on a single variable: cost. This led to the perception of procurement as a back-office function, which is still the case today in some companies. Today, however, many leaders recognize that a high-performing procurement organization can directly contribute to the bottom line and improve shareholder value. The result is increased attention to supplier performance management, from strategy to organization to tools and techniques.1

The supplier performance management imperative is driven by several factors. It is a given that we are in an age of relentless competition. Pressure to continually lower costs is often passed down to suppliers. Compounding these difficulties is the spread of outsourcing across multiple industries, which has led to the disintermediation of the traditional value chain and the advent of complex supply chain networks. Add to this the supply constraints inherent in many industries and the shifting nature of customer demand, and it is clear that supplier relationships are of critical importance to the success of most enterprises.

A core element of the new view of procurement is that the function must deliver more than reduced costs. While this concept is not new, the tools used by organizations to track supplier performance have evolved considerably in recent years. One tool, the supplier performance scorecard, has become particularly popular. Supplier performance scorecards are based on the original balanced scorecard, which codified the idea that many different components contribute to organizational success.2 Applied to suppliers, scorecards have been instrumental in changing the view that cost alone is enough to ensure successful performance. The explicit introduction of additional variables such as service, quality and innovation has led to a broader, more holistic approach to supplier performance management. Indeed, a review of the popular and published literature on supplier management shows a growing emphasis on supplier performance scorecards as essential tools for effective performance.3

Despite the availability of supplier scorecards and other tools, some organizations still stress annual, targeted cost reductions from their suppliers — or, at best, soft metrics such as supplier-buyer “relationships,” a construct that is neither concrete nor appropriately valued. Probably the most infamous example is the U.S. automotive industry in the 1990s, when extreme competitive pressures led to a singular focus on cost and hence adversarial relationships with the industry’s supply base. Instead, leading companies are discovering a powerful use of supplier performance scorecards: to establish dual accountability with their suppliers.

Dual Accountability and the Two-Way Scorecard

The Two-Way Scorecard is a tangible means of embedding cooperation in the supplier-buyer relationship. Simply stated, the Two-Way Scorecard is a performance tool that measures supplierand buyer results across a balanced set of categories and, within those categories, tailored metrics for each party. At Johnson & Johnson Group of Consumer Companies Inc., which adopted dual accountability in 2003 as a means of improving product launches and operations management, the Two-Way Scorecard is fundamentally a means to break the supply chain function into measurable subprocesses, for which the buyer and strategic suppliers each have specific accountabilities and performance standards to achieve. A high-performing supply chain depends on strong showings in each subprocess. By tracking performance to identify specific weaknesses in the supply chain, the two sides can take joint responsibility for improvement.

While the Two-Way Scorecard is the most visible aspect of the commitment to dual accountability, it would be a mistake to consider simple adoption of this tool as the only step needed. The buyer and the supplier each have to make a multilayered commitment across their enterprises. (See “Ten Keys for Successful Implementation of Dual Accountability.”) Achieving true dual accountability has two broad phases: laying the foundation (by determining the strategic prerequisites) and tactical deployment (ensuring the concept is optimally structured and utilized).

Laying the Foundation

This begins by establishing that the buyer company’s operating values are consistent with dual accountability and a commitment to meet suppliers halfway. At J&J, the foundation is embedded in the company’s credo, with a directive in the first paragraph that states, “Our suppliers and distributors must have an opportunity to make a fair profit.” While it is common for companies to pay lip service to the value of strategic supplier commitment, putting it in writing represents a throwing down of the proverbial gauntlet — a challenge to the buyer to complete his end of the bargain.

Given that dual accountability requires considerable time and effort from the buyer, it is also important that the organization be clear about which of its suppliers are truly strategic to its business. Many criteria can be used to define strategic suppliers, such as dollar impact on the end product, material quality impact, constrained supply base and significant specialist knowhow. Whichever criteria are used, the key is to develop unambiguous internal consensus around this shortlist, ensuring clear commitment across senior management.

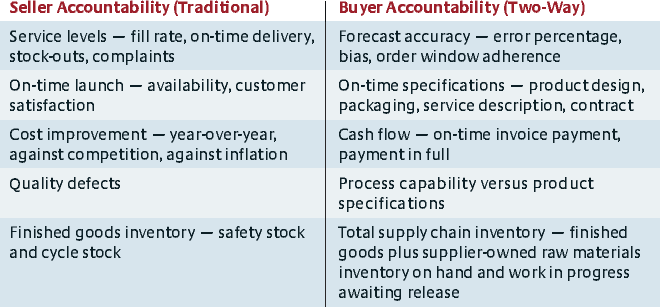

The third brick in the foundation relates to the design of the Two-Way Scorecard. Metrics must be chosen that make sense for the specific relationship, and there must be a similar number of metrics for both supplier and buyer. This principle is an essential aspect of dual accountability; its importance is easy to understate, yet it is difficult to implement. The metrics of the Two-Way Scorecard require very careful assessment if they are to work. At J&J, supply chain performance is measured across five components: execution, compliance, financial impact, new products and partnership. However, the specific metrics for each category cannot be prescribed but must be tailored to the two parties’ common goals. (See “Traditional Supply Chain Metrics Versus the Two-Way Scorecard.”)

Traditional Supply Chain Metrics Versus The Two-way Scorecard

Traditional Supply Chain Metrics Versus the Two-Way Scorecard

Metrics for the Two-Way Scorecard must be tailored to the two parties’ common goals; they cannot be unilaterally determined or prescribed in advance. There should be a similar number of metrics for both supplier and buyer in order to maintain the principle of dual accountability.

Tactical Deployment

Deploying the dual accountability concept requires a sustained commitment from both parties. Four important points should be emphasized in implementing the Two-Way Scorecard:

- Identify a single point of responsibility. Within both the supplier and buyer organizations, a single individual should play the role of central coordinator to manage the relationship and ensure that the overall goals of the partnership are being met. This person coordinates the metrics across the relevant departments and updates the scorecard.

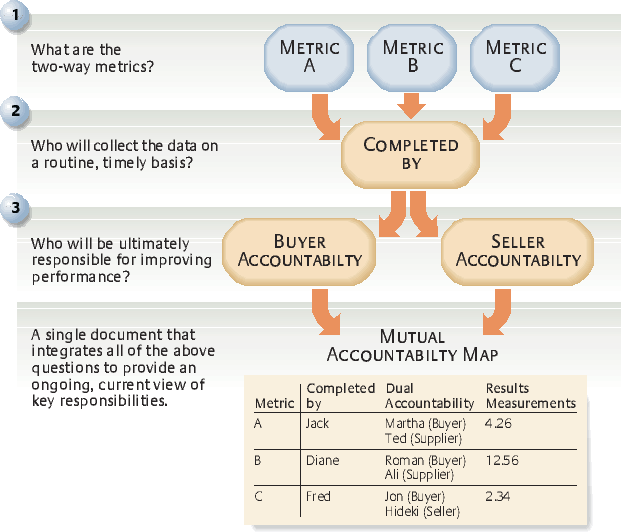

- Create a mutual accountability map. A clear view of individual responsibilities for the various scorecard metrics is essential. At J&J, the Two-Way Scorecard is complemented by a “mutual accountability map.” This document clarifies two fundamental questions: Who is capturing the appropriate information on a routine, timely basis, and who is ultimately responsible for improvement? The buyer and seller may well have different roles in achieving a shared goal. (See “Specifying Individual Tasks With a Mutual Accountability Map.”)

- Form a cross-functional team. A successful partnership will involve multiple individuals across both organizations, typically encompassing procurement, manufacturing, finance, engineering, quality and other areas. These people should be brought together into a performance management team, with one or more representatives from each impacted functional area. The management team is co-chaired by the central coordinators from each organization, who work together to ensure the process is maintained and team objectives are met.

- Conduct consistent periodic reviews. The performance management team will typically require two sets of meetings. The first are preparatory sessions between buyer and supplier representatives to talk through specific functional issues. The second is a full performance review. It is helpful to hold this meeting at the supplier’s site, both to show the importance that the buyer places on dual accountability and to emphasize operational concerns — what are the issues, how should they be tackled, by when and by whom?

Specifying Individual Tasks With A Mutual Accountability Map

Putting Dual Accountability Into Practice: Case Examples

At J&J, the Two-Way Scorecard has been put into practice with strategic suppliers over the last four years. Positive results have been seen in a range of areas, from resolving potential supplier liquidity problems to addressing the inefficiencies of global trading. Several habitual pain points have eased, most notably new product launches. In the past, the launch of a new product was a classic exercise in finger-pointing. J&J would develop a winning concept, agree on a target launch date, and then “backwards schedule” the due dates with its suppliers. Suppliers learned of their roles in the launch with a great emphasis on their deadlines, but they often were missing critical information, such as manufacturing specifications, launch quantities or final copy clearance. Frustrations grew when last-minute changes, seemingly minor in nature (for example, “Wouldn’t a darker shade of red make the label more appealing?”), slowed suppliers and cascaded through frozen time horizons. All this changed with the advent of dual accountability. Two-Way Scorecard measurements for J&J’s process adherence showed a need for improvement. After J&J leaders realized that the root cause of delayed launches was often a combination of supplier and buyer behavior, they launched a series of projects to address the gaps. Such self-reflection is nearly unthinkable in most companies the size of J&J.

The supplier testimonials of dual accountability’s effectiveness are impressive. “In relating to our clients such as J&J,” said one longtime supplier, “we have found that the best relationships are those that measure not only how we are performing for them but how well they are, in turn, performing for us. Having measurements that look at order fill rates compared to forecast accuracy, new product launch timing compared to the timely delivery of launch support information, and product cost improvement opportunities presented as compared to the timely payment for goods delivered are key. We have also found open, honest and ongoing dialogue between the two parties to be the best approach to maintaining a relationship, leaving the supply agreement to collect dust, only being used as a last resort.”

A crucial aspect of dual accountability is that it enables a deep understanding of what makes one’s partner tick. Lasting success in a supply chain relationship requires both parties to learn the other’s culture and key priorities; company culture in a small or midsized strategic supplier is likely to be vastly different from that of a highly matrixed, multinational buyer. Understanding these differences is the key to blending the two cultures in pursuit of a common goal. To accelerate this learning, J&J supplements the Two-Way Scorecard with a resource-sharing model with its strategic suppliers. J&J places new staff into externships that embed the employees in the day-to-day operations of its suppliers. The externships can last for as little as six weeks or up to six months. The knowledge and experience gained by both parties is invaluable in aligning the two organizations. J&J staffers learn about their suppliers’ critical success factors, which helps them focus on the right performance indicators and in turn better deliver on J&J’s buyer commitments. The supplier gets someone who can explain the finer points of J&J’s requirements and help apply them to its own needs. J&J has recently expanded the resource-sharing model by bringing people from its strategic suppliers into its headquarters for similar externships.

While J&J provides an example of the Two-Way Scorecard’s deployment, the broader concept of dual accountability has been put into practice at other companies as well, including Toyota Motor, Home Depot and Neways.

Long recognized for its ability to foster strong supplier relationships, Toyota Motor Engineering & Manufacturing North America Inc. has applied the concept of dual accountability through the 90-plus North American companies forming the Bluegrass Automotive Manufacturers Association. In 2005, BAMA created a Voice of the Supplier Committee. This committee is encouraged to make suggestions and complaints to Toyota without fear of reprisal. Results include Toyota’s expanded investment in its Internet-based World Wide Automotive Real Time Purchasing Network to alleviate concerns that the system did not sufficiently improve suppliers’ processes and movement toward a standard methodology for measuring defective parts per million, the lack of which had caused much conflict with some suppliers. Toyota also established a supplier relations division within its North American purchasing operation “to eliminate the unnecessary burdens [on suppliers] caused by Toyota,” according to a Toyota executive.4

The Home Depot Inc. established an online supplier performance scorecard, which displays results for a range of metrics in graphical format, in 2006. Home Depot also formed a Supplier Council, comprising 15 of its most strategic suppliers, to meet every quarter and collaborate on multiple initiatives. At these meetings, the suppliers learn how Home Depot does business and how best to support the company. Home Depot also hosts regular supplier workshops and holds focus groups with suppliers to elicit their input.5

A final example comes from Neways Inc., a network (nonretail) marketer of health and wellness products, which has taken dual accountability to an extreme few companies have considered. As Neways grew, its core product line evolved around “liquid nutritional” technology — natural fruit drinks containing unique and proprietary ingredients. Historically, these products were made by contract manufacturers because the manufacturing process required significant capital investment. In early 2007, Neways realized that its current supplier had a significant processing technology edge over other potential providers. At the same time, the supplier was seriously considering direct alliances with retail-oriented customers. Despite accounting for only 10% of the supplier’s output, Neways made a strategic investment to acquire a significant portion of the company, to the point of gaining board representation. The day-to-day operations of the supplier remain with the original leadership team, which continues to pursue retail-oriented customers to grow its business, and at the same time Neways’ source of low-cost, high-quality supply is ensured as it expands into additional markets and products. But the partnership has deepened the two companies’ involvement in each others’ operations. Neways has adjusted order timelines to smooth out supplier production demand, for example, while the supplier has shared new, alternative formula technologies based on its real-time knowledge of the market.

The Value of Shared Responsibility

Dual accountability offers benefits that transcend those of more traditional approaches to supply chain optimization. The greater transparency and impetus for dialogue engendered by dual accountability lead to a deeper understanding of core, underlying issues on both sides. In this way, suppliers and buyers launching new relationships can start off on the right foot, while existing supply chain marriages that have gone “stale” can be revitalized. Too many strategic supplier relationships today operate without a basis of trust and with an adversarial undertone. The affiliation continues because of some perceived necessity, such as high switching costs or limited options, and as a result, interactions often have a subtle combative element.

Dual accountability, whether through the Two-Way Scorecard or other methods, allows for new role expectations and a fresh start. Successful practitioners of dual accountability will see tangible results in five interrelated areas:

- Stronger partnerships. As a result of the greater openness between partners, suppliers can become knowledge agents for the buyer, providing competitive intelligence to which the buyer otherwise would not have access. It is now commonplace at J&J for strategic suppliers to openly suggest refinements to new products or even “white space” concepts, with confidence that their ideas will be given appropriate consideration and credit.

- Improved performance. Despite the advancement of information management, many companies continue to struggle with the infamous “bullwhip effect,” in which inventory piles up between supply chain points.6 The increased communication and multidimensional metrics facilitated by dual accountability eliminate inventory-related and other inefficiencies.

- Reduced risk. The flip side of consistent performance is minimizing uncertainty and keeping surprises to a minimum. Buyers and suppliers taking dual accountability seriously operate with as close to full knowledge of one another’s operations as possible, while looming issues are identified and addressed early on. Given the global nature and resulting complexity of most supply chain networks, the importance of reduced risk cannot be overstated.

- Improved company reputation. The easier an organization is to do business with, the more suppliers will want to work with it. Consider the case of a major European telecommunications company we interviewed that lost money because of a supplier’s mistakes. Instead of claiming for liquidated damages, the telecom executives told the supplier to invest that sum in fixing the problem. If the buyer is seen as fostering collaboration and openness and is willing to create win-win situations, then the supplier community will view the buyer as a higher-caliber organization and approach the relationship as one clearly worth investing in. The telecom company improved its reputation not only with the individual supplier but also with the supplier base in general.

- Lowered total cost. This is the ultimate benefit of the concept of dual accountability. The aforementioned telecom company sent its product design plans to suppliers, asking for early feedback. The suppliers came back with improvements in how the cabinet wiring should be routed, resulting in 2.5 fewer meters of expensive cabling per cabinet, which, when multiplied many times, added up to real money. Yet saving on cost was not the original emphasis; instead, the telecom company sought to improve performance.

The Role of Technology

As with other management innovations, technology has the potential to ensure the long-term sustainability of a dual accountability initiative. Information systems are important tools for populating a Two-Way Scorecard efficiently and accurately. This is true especially for companies that have been involved in mergers or acquisitions, which usually result in a myriad of siloed internal information systems. The result is data that is not easy to interpret, much less integrate into a consistent view.

Technology providers have recognized this problem and have spearheaded the trend toward greater integration and cohesion among members of any given supply chain. These technology solutions include direct linkages with external constituents, such as electronic data interchange with strategic suppliers; middle-ware connecting interdependent information systems such as separate enterprise resource planning systems installed by buyer and suppliers; and the rapid development of online, Web-based solutions, including customized portals and extranets.

However, such solutions are significant investments, and even after the installation of information systems, it takes time for companies to reach the ideal of integration. In fact, the technological foundation for a Two-Way Scorecard can be as simple as the common spreadsheet. Versatile and easy to use, the spreadsheet is the most basic tool available — and for many organizations it will remain so. The key variables lie in the collection, interpretation and analysis of data to ensure that the correct questions are answered. Getting this right requires experienced analysts to “work the systems” and extract the relevant data, which then can be populated in the spreadsheet. The key is to assign a single analyst at each end to manage and drive the process. It is important to convert individual analysts’ expertise into institutional know-how. This can best be accomplished through clear process documentation, transparency and tweaking of information systems to deliver the right data elements, so that they can be routed to the right metrics on the scorecard. Given the significant amounts of work involved, it is all the more critical that only the most important supplier relationships are covered and that the right sets of metrics are chosen.

The ultimate end state is some form of automated, Web-based Two-Way Scorecard that operates in real time. ERP systems today contain dedicated supply chain performance evaluation modules, while there is no shortage of vendors offering online performance scorecard technologies, whether custom built or off the shelf. This is a glimpse of the future. Because of the time and money involved, however, companies cannot reach this ideal unless they already have broader plans in place to integrate their internal systems (typically migrating to ERP systems), eliminate legacy systems and move toward greater data integration with their suppliers. Such investments will be merited for truly critical supplier relationships, but organizational learning comes slowly. Consensus and buy-in must be built over time rather than in one fell swoop, no matter how compelling the rationale.

WHILE SUPPLY CHAIN RELATIONSHIPS are widely recognized as integral to a company’s operations, it is safe to say that the concept of dual accountability is still in its infancy.

For many corporations, the dual accountability concept — whether evinced through the Two-Way Scorecard or another method — can serve as a tangible means of revitalizing those unfulfilling supplier marriages. True, some marriages are beyond repair, and the baggage is so great that divorce is the only option. Many others can be salvaged, however, with hard work, dedication and a commitment to build trust. In this way, buyers can ensure long-term relationships with their suppliers —exactly like a successful marriage.

References (1)

1. R.J. Trent, “Why Relationships Matter,”