Changing How We Think About Change

Innovation is not in itself a strategy but the mechanism for achieving a change in either magnitude, activity, or direction.

Topics

The Strategy of Change

A major challenge for business leaders is knowing when to stay the course and when to change direction. There is conflicting advice. Thousands of articles have been published on the topic of change management in leadership, but just as many have focused on the key roles of persistence, grit, and commitment — that is, not changing — in overcoming challenges.

As former U.S. Army Chief of Staff Eric Shinseki famously remarked, “If you dislike change, you’re going to dislike irrelevance even more.” Change may be inevitable, but it can be hard for business leaders to identify the nature, scale, and timing of the change that is appropriate for their company’s specific context. As operating environments become more dynamic, both the benefits and risks of change become amplified.

Just as the word ride can describe both a white-knuckle experience on a rollercoaster and a leisurely excursion on a bicycle, change is used to describe a wide variety of contexts. We assert that a fundamental source of confusion among managers and executives is the use of that single term to refer to three very different strategic responses to business challenges.

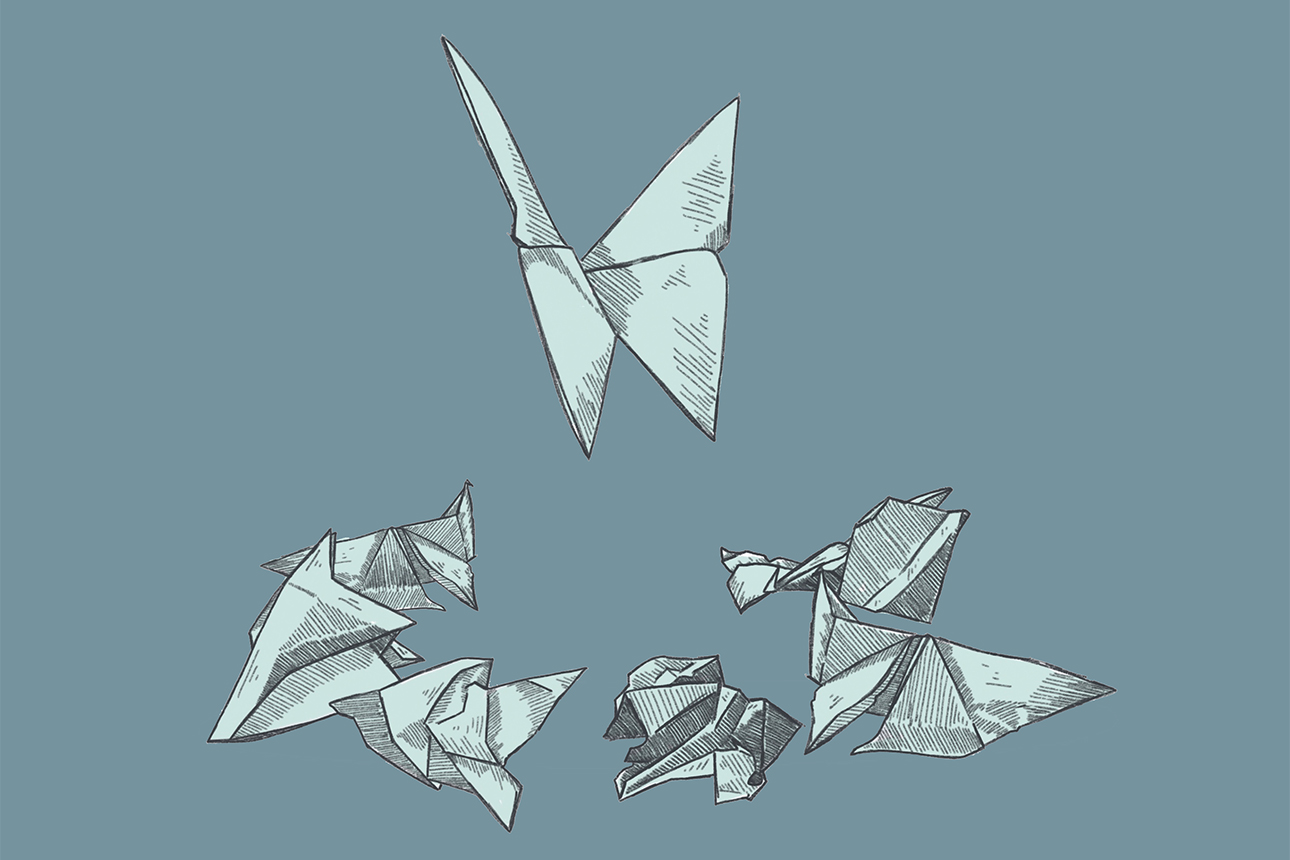

Change can involve magnitude, activity, or direction, and the first step toward a clearer vision for change is to clarify what form of change should be considered:

- Magnitude: “We need to enhance our execution of the current path.”

- Activity: “We need to adopt new ways of pursuing the current path.”

- Direction: “We need to take a different path.”

Companies that have doubled down on flawed or outdated business strategies, for example, Kodak, Nokia, Xerox, BlackBerry, Blockbuster, Tower Records, and J.C. Penney are guilty of believing that a change of magnitude was sufficient instead of either a change of activity, such as adopting new technologies or distribution channels, or a change of direction, such as exiting certain businesses altogether.

Contrast these examples with companies whose ambitions led to risky changes in direction when their context called instead for changes of activity or magnitude: GE’s attempts to be a first mover in green energy and the industrial internet of things through Ecomagination and Predix; Sony’s move into entertainment content; or Deutsche Bank’s efforts to become a global investment bank.

Many of the most impressive and successful corporate pivots of the past decade have taken the form of changes of activity — continuing with the same strategic path but fundamentally changing the activities used to pursue it. Think Netflix transitioning from a DVD-by-mail business to a streaming service; Adobe and Microsoft moving from software sales models to monthly subscription businesses; Walmart evolving from physical retail to omnichannel retail; and Amazon expanding into physical retailing with its Whole Foods acquisition and launch of Amazon Go.

Further confusing the situation for decision makers is the ill-defined relationship between innovation and change. Most media commentary focuses on one specific form of innovation: disruptive innovation, in which the functioning of an entire industry is changed through the use of next-generation technologies or a new combination of existing technologies. (For example, the integration of GPS, smartphones, and electronic payment systems — all established technologies — made the sharing economy possible.) In reality, the most common form of innovation announced by public companies is digital transformation initiatives designed to enhance execution of the existing strategy by replacing manual and analog processes with digital ones. At best, these are changes of magnitude.

In fact, it’s rare that an enterprise successfully uses digitalization as the opportunity for a fundamental reinvention of its business. But this is exactly what Shenzhen-based Ping An has done by transforming itself from a traditional provider of insurance products into the provider of five technology-enabled ecosystems, including China’s largest health care platform.

To address the ambiguity around the word change, and to better understand how innovation supports each form of change, let’s parse the distinctions between magnitude, activity, and direction and examine when each is the appropriate course of action.

Understand Why, When, and How to Change

There are two diagnostic questions that business leaders and their executive teams should use to assess the nature, scale, and timing of the change required in their specific context:

- Is the strategy fit to purpose? This question establishes whether the current or proposed strategy is valued by an attractive and accessible audience — measured by size of market, willingness to pay, and business model appropriateness — and the level of resource outlay required to scale the strategy.

- Can relative advantage be sustained? This question assesses whether the current or proposed strategy delivers meaningful differentiation — that is, a “difference that makes a difference” to the attractive, accessible audience — and the durability of the competitive advantage created by that difference.

The graphic “Diagnosing Fit to Purpose and Relative Advantage” identifies criteria by which these key decision makers should evaluate the performance of their business on each of two criteria.

This analysis is then used to chart the company’s position on the MAD (Magnitude-Activity-Direction) Change Matrix (MCM) (see the graphic below), providing insight about whether change should take the form of magnitude, activity, or direction. For example, if the consensus reveals high fit to purpose and high relative advantage, this points toward change in the form of enhanced magnitude within the current course. Having low fit to purpose and low relative advantage, however, sounds the alarm for implementing a fundamental shift in direction, defining a new strategy on a new path. The remaining cells in the matrix help distinguish the appropriate response to more nuanced combinations of fit to purpose and relative advantage.

Leaders at 3M used the MCM framework to determine the company’s response to increasing competition in one of its key markets as new entrants launched cheaper products. The instinct of senior leadership in 2018 was that a change of direction for a line in the company’s electrical products division was required, possibly one that involved exiting the market. The consulting team tasked with aiding 3M’s analysis came to a different conclusion after taking a closer look: 3M enjoyed a strong fit to purpose and relative advantage. Lower-cost entrants might undercut the company’s pricing, but their competitive offerings were clearly inferior.

The MCM framework thus revealed that the best response for 3M would be to increase the magnitude of the company’s existing actions. Accordingly, it refined promotional efforts to better articulate its product’s distinct advantages and to educate the market about the risks of using a lesser alternative. 3M also committed resources to bolster the product’s functional value without increasing the cost to customers. This combination of education and promotion significantly enhanced the value proposition perceived by 3M’s customers, leading to further increases in market share, revenues, and, ultimately, profits.

Contrast this with the situation faced by Fujifilm in 2005. Drawing on the strategic thinking that had enabled it to supplant Kodak as the leading provider of chemical film in the 1990s, Fuijfilm was alert to signals emerging that its now core offering — digital cameras — was in turn becoming commoditized. Analysis revealed that the company had low relative advantage because cameras of sufficient quality were being incorporated into smartphones. In response, the company implemented a major reorganization to support its diversification into industries such as pharmaceuticals and cosmetics while leveraging its reputation as an imaging company to become a provider of high-fidelity imaging for medical applications.

A wide range of distinct business decisions are often conflated under the broad rubric of “change and transformation management.” Our work with executives around the world validates that the strategic choices facing business leaders can be clarified by distinguishing between the three dimensions of change: magnitude, activity, and direction.

Business leaders also must be mindful that innovation is not in itself a strategy. Innovation is instead the mechanism for achieving a change in either magnitude, activity, or the less common and more dramatic requirement of heading in a different direction.

The dynamic nature of modern business keeps business leaders constantly questioning how to adapt their strategy to maintain their competitiveness. With the clarity provided by the MAD change matrix, business leaders can identify which form of change is most appropriate to their company’s context. While any form of change can be described as “new” and “different,” only the right form of change qualifies as “better.”

Comments (4)

Ambreen Ali

Adolfo Ramirez

Tom Hunsaker

Alberto Brito